By Roger Silverman,

First published on the Oakland Socialist website, https://oaklandsocialist.com/2017/10/20/the-russian-revolution-turns-100/

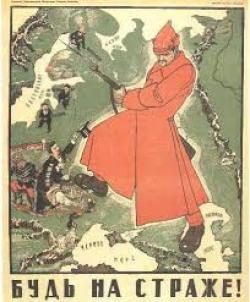

November 7th, 2017 marks the centenary of an event whose impact still today reverberates throughout the world. The Russian revolution remains a constant spectre at the feast of the rich, its shadow falling across all subsequent history. Since its lessons lie buried in a century of sludge by all those determined to malign its meaning, it is the duty of socialists to unearth them and bring them back to light.

There will be no shortage of articles and speeches commemorating it: some dismissing it as a wicked conspiratorial putsch, some ascribing to it all the subsequent horrors of the twentieth century, others still painting gaudy anniversary chocolate-box extravaganzas in its honour. What matters is that this was one of those rare moments when ordinary people took control of their own lives. People humbled over generations to eke out a miserable anonymous existence of hardship and submission suddenly rose up and stormed the stage, determined for once to grasp hold of their destiny and shape history to their needs.

A paradox

Russia entered the twentieth century as a vast empire spanning one-sixth of the earth’s surface – a land of savage despotism ruled by the Tsars. Its most notorious contributions to the world’s vocabulary had been words like knout (the instrument of torture by which prisoners were whipped, often to death) and pogrom (the frenzied mob massacre of a terrorised minority community). By 1917, Russia was further crippled by years of slaughter on the eastern front of the first world war, in which some three million Russians perished.

Organised into democratic councils of workers’, soldiers’ and peasants’ deputies elected at every unit of labour with direct right of recall, working people briefly held the power in their own hands. Tsars and landowners, racists and bureaucrats, generals and executioners, capitalists and renegades were swept into oblivion. Production was for the first time in history to be rationally planned rather than subordinated to private profiteering and the blind forces of the market.

And yet the October revolution (so named in accordance with the then current calendar) remains a gigantic paradox. It was greeted worldwide as the first step towards a new era in history: a socialist civilisation. And yet the regime which was soon to emerge from it became one of history’s most bloodthirsty tyrannies. Its ideals were soon to be perverted into a hideous mockery of socialism. Millions of workers were to perish in the torture chambers and slave camps of Stalin’s police state. And in 1991 the crumbling relic of the “Soviet Union” finally collapsed in ruins.

Apologists for capitalism are fond of crowing that Russia’s current economic devastation is an indictment of decades of “socialism”. The truth is exactly the opposite. On the contrary: it was the downfall of the prevailing system of state ownership, by then rusting and creaking under the deadweight of bureaucratic mismanagement, that saw Russia transformed into a wasteland ravaged by adventurers and cowboy gangsters, largely former bureaucrats. It was with the restoration of a raw and primitive capitalism that Russia was brought to the brink of catastrophe, devastated by what was probably the sharpest drop in production and living standards that any country has ever endured. Real gross domestic product fell by more than 40%, bringing hyperinflation, lawlessness, destitution and despair. If Russia’s economy later gained a very marginal and temporary respite, it was only due to a short-lived boost in world oil prices.

What a contrast with the formative years of the planned economy! Even in the thieving hands of a greedy and wasteful parasitic elite, the very survival over three quarters of a century of the nationalised economy – not to mention its later extension to swathes of Eastern Europe, Asia and beyond – fatally belies the capitalists’ triumphalist sneers.

It is worth remembering that in earlier days, for all its devastating burdens, the planned economy had boasted miracles of economic transformation. To take a measure of what was then achieved, in the fifty years starting from 1913 (the highest point of the Russian pre-revolutionary economy), Russia’s share of total world industrial output had soared from 3% to 20%, and total industrial output had risen more than 52 times over. (The corresponding figure for the USA was less than six times.) In the same period, industrial productivity of labour had risen by 1,310%, compared to 332% in the USA, and steel production from 4.3 million tons in 1928 (at the start of the first Five Year Plan) to 100 million tons. Life expectancy had more than doubled and child mortality dropped nine times. Soviet Russia in its heyday produced more scientists, technicians and engineers every year than the rest of the world put together.

These spectacular achievements have no parallel. They are even more startling than they seem, in that in this same period Russia had endured two world wars in which up to 25 million lives were lost, one civil war, one defensive war against 21 armies of foreign intervention, two devastating famines, the paralysing convulsions of the Stalinist purges and the constant deadweight of heavy-handed dictatorship. Steady growth had been confined to the period between the start of the first Five Year Plan in 1928 and the beginning of the Stalinist terror in 1937, followed by the outbreak of war in 1941, and then, after post-war reconstruction, from 1950 onwards – hardly a quarter of a century in all. And all this had been achieved in the teeth of Russia’s terrible handicaps – a heritage of backwardness and illiteracy, a hostile capitalist encirclement and a vast murderous parasitic bureaucracy clinging on to its back.

The weakest link

It was at its weakest link that the chain of capitalism had first snapped. Russia in 1917 was a semi-colony. For every hundred square kilometres of land, there were only 0.4 kilometres of railway track. 80% of the population scratched a bare existence out of their tiny strips of land, using the most primitive tools and methods. Agriculture was fragmented into nearly 24 million smallholdings. Over 70% of Russian subjects were totally illiterate, and what reactionary priest-ridden education there was focused only on rearing a new generation of bureaucrats within the elite. Heavy industry was dependent on foreign finance capital; French, British, Belgian and other Western investors owned shares amounting to 90% of Russia’s mines, 50% of her chemical industry, over 40% of her engineering plant, and 42% of her banking stock.

Russia had experienced no bourgeois revolution clearing away feudal restrictions, as in the West. With its vast under-populated territory overrun throughout the centuries by nomadic hordes, Russia had a very weak, sluggish economic development. Capitalism had been too weak to achieve political power through the peasant revolt of the eighteenth century or the abortive coup d’etat of 1825, and had arrived on the scene too late to hope to compete with the modern Western monopolies on the world market or pursue an independent historic role. It was bound hand and foot to the Tsarist autocracy at home and the big financiers abroad.

A belated spurt of development only came following the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, whereby the absolutist monarchy began to balance more heavily on liberal landowners, nascent capitalists and foreign bankers, releasing reserves of manpower for industry. Thus, capitalism in Russia did not evolve in such a way as to rest securely on a wide stratum of intermediate small business entrepreneurs, stable capitalist farmers, etc.; lacking any solid social foundation, it hung precariously suspended over society by world imperialism on the strings of the Holy Tsar.

Thriving on substantial foreign investment, industrial enterprises now sprang up using the most sophisticated machinery and production techniques. Russia’s belated growth prepared the rapid development of a concentrated industrial working class, and with it a welcome new culture of solidarity and militancy. In 1914, while 17.8% of American industrial workers were employed in factories with over 1,000 workers, the corresponding figure in Russia was as high as 41.4%, and higher still in Moscow and Petrograd. Young peasants streaming off the land found themselves suddenly plunged into great mechanical sweatshops of the most intensive exploitation, and they came fresh to the realities of industrial class struggle and militant organisation more rapidly than their counterparts in the West, with their gradual evolution through intermediate stages of handicraft and manufacture.

The early Russian socialists had been “populists” who believed that the Russian peasantry could jump straight into a peculiarly Russian rural form of “communism”. Paralysed by the inertia of the masses, they sought short cuts to utopia through evangelism and terrorism alternately. First they descended on the villages preaching revolution, only to find themselves indignantly turned over to the police. Then, after twelve years’ efforts, they managed to assassinate a Tsar; the ruling caste having had no difficulty finding a new one, the outcome was a wave of executions and renewed repression.

It was the stirrings of the Petrograd workers in the stormy strikes of the 1890s that first established Marxism in Russia. Soon came the revolution of 1905 – the biggest upheaval in Europe since the Paris Commune of 1871. Independently of any theorist or “agitator”, the workers spontaneously formed the first soviets (democratically elected workers’ councils). In face of the workers’ radicalisation, the capitalist politicians hastily abandoned their tentative liberal demands for a measure of control over the monarchy. It was becoming clear that any effective challenge to the tottering regime could only come from the workers.

Prior to the outbreak of the revolution, the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (the Socialist International’s Russian affiliate) found itself split over the nature and goals of the coming revolution. Confining its outlook within the boundaries of Russia, the “moderate” Menshevik wing of the RSDLP could envisage no bolder aspiration than the installation of a liberal-democratic government which would then mechanically retread the path of Western capitalism. According to their sterile formula, until the entire historic mission of capitalism had been fulfilled and the economy had attained Western levels the role of the workers’ parties would be to serve indefinitely as a loyal opposition.

The Bolshevik wing considered this theory narrow and pedantic. They placed no reliance on a weak capitalist class inextricably entangled with foreign imperialism and hopelessly compromised by its collaboration with the despotic Tsarist state machine. Placing the role of the Russian revolution firmly within internationalist horizons, they predicted that the victory of a democratic agrarian revolution in Russia led by the workers and peasants would act as an explosive catalyst precipitating socialist revolution throughout Europe.

Along with the Bolsheviks, Leon Trotsky (at that time independent of both wings) also envisaged the coming revolution in Russia as the first breakthrough of the workers of the world into the future, while also arguing that the Russian workers, supported by millions of poor peasants and allied to the workers of the metropolitan countries, could be the first to overthrow capitalism, in alliance with the workers of Europe, leading the revolution inexorably onward to socialist measures. While a capitalist Russia could only remain a semi-colony of Western imperialism, socialism could only be built hand in hand with the workers of the advanced countries.

The events of 1917 quickly settled the argument. In February, against a background of famine and starvation, riots on the bread lines, a bloodbath on the battlefields, scandal in the palace, mutinies by soldiers and even by the elite Cossack forces… it took just eight brisk days of street protests, led above all by the defiant women of Petrograd, to bring the 300-year-old Romanov dynasty crashing to its downfall.

A coup?

Five times in the course of the next nine months the people poured on to the streets in defence of their gains. In April, demonstrations led by the Bolsheviks forced the direct agents of capitalism out of the “Provisional Government”, and by their simple slogans and skilful propaganda the Bolsheviks exposed the impotence of the hand-wringing apologists for compromise with the liberals. Far from the stock caricature of the Bolsheviks as irresponsible rabble-rousers, when in July the workers of Petrograd and the soldiers of the local garrison took to the streets again, impatient for a quick resolution of the impasse, it was the Bolsheviks who had to urge restraint until the provinces had caught up with them. Then, in August

Petrograd was threatened with a bloody defeat at the hands of the advancing troops of the fascist General Kornilov. The Kerensky Government found itself helpless, paralysed by its subservience to a ruling clique which feared the Bolsheviks a thousand times worse than the relics of Tsardom, and it was the Bolsheviks who organised the workers and soldiers of Petrograd in a united front with Kerensky to repel Kornilov. Months of patient explanation against a dramatic background of events won an overwhelming majority to the side of the Bolsheviks, and the insurrection of 25th October (7th November in the new calendar) in the name of the assembling congress of Soviets met with negligible resistance.

The lazy hackneyed argument of most pro-capitalist historians is that the October revolution was a conspiracy organised behind the scenes by a secretive Bolshevik cabal: a “coup”.

The truth is that at the time of the collapse of the Tsarist regime the Bolsheviks had numbered no more than 8,000 throughout the length and breadth of Russia, with its population of more than 150 million. Once the Tsarist regime had fallen, the so-called “Provisional Government” which had stepped uninvited into the vacuum had no following in the Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasants which had sprung up overnight as a true parliament of the masses. Caught unawares and overcome with confusion, the local Bolshevik leaders on the spot (among them Stalin) prepared to join forces with the Mensheviks. Lenin returned to Russia in April to find the Bolshevik party thrown into confusion by the unexpected fall of Tsarism and the assumption of power by liberal politicians. Greeted on his return with bouquets and flowery speeches by Menshevik leaders, Lenin spoke over their heads to the crowds, welcoming the “advance guard of the world proletarian army“, condemning the capitalist government and calling for the victory of Soviet power. On this basis, Trotsky’s group promptly joined the Bolsheviks.

Within five months their membership had grown more than twenty-fold, to 177,000. And by September, on the eve of the revolution, in the words of Sukhanov (a Menshevik, by the way, and a bitter enemy of Bolshevism): “for the masses, [the Bolsheviks] had become their own people… They had become the sole hope… The mass lived and breathed together with the Bolsheviks.”

The overthrow of the capitalist government had been a simple matter of hours, with practically no fighting in the capital and only a short burst of gunfire in Moscow. The Russian ruling class had forfeited all authority, and the “socialist” stooges in the “Provisional Government”, behind whom they had been forced to shelter after April, had lost all trace of credibility. The people were clamouring for “peace, bread and land”. Kerensky had led a million more to the slaughter on the front, halved the bread ration, and turned his guns on to peasants spontaneously taking over the great landed estates. No one respected theory more than Lenin, but he summed up very simply what had happened: “The masses learn more in a day of social revolution than in decades of socialist theory…An ounce of experience is worth a ton of theory.”

There is another variant of the same argument: was the October revolution perhaps a mistake? As if we could construct our own historical context…

The insurrection was conceived by an entire generation of militant Russian workers as merely a preliminary step towards a European-wide socialist revolution. If they had let slip the opportunity, the alternative could only have been a bloody defeat at the hands of General Kornilov, the contemporary Franco or a Pinochet, from which it would have taken one or two generations to recover. It was taken for granted that unless it were to spread westwards, the Russian revolution would inevitably be crushed. No one at the time could have conceived of the possibility that the Soviet state could survive in isolation for decades, even as a grotesquely mangled bureaucratically deformed monstrosity.

Driven beyond breaking-point by slaughter at the front and hunger at home, the Russian workers, soldiers and peasants had overthrown their oppressors. If they had foreseen the tribulations ahead of them in 1917, would they have launched their revolution? Who can say? History had not granted them the luxury of contemplation. They were impelled by the immediate duress of slaughter at the front and hunger at home. It was not their revolution but its isolation in conditions of virtual barbarism – the failure of the revolution elsewhere, not their victory at home – that doomed them to the privations ahead.

In the hour of danger that was approaching, with the brutal intervention of no less than twenty-one armies of foreign capitalism, it was the active support of working people throughout Europe that was the crucial factor in saving the revolution from defeat.

Internationalism

Power was at last concentrated in the hands of democratically elected representatives of the urban workers and of soldiers recruited from the peasantry. But for how long could they hold it?

It was not at all fanciful for the Russian workers to rely on their counterparts throughout Europe to come to their aid. It was an absolutely reasonable, practical and almost commonplace assumption that had led them to place their struggle firmly in the context of a Europe-wide revolution. After all, as late as in November 1912, meeting at an Extraordinary International Socialist Congress at Basel, the Socialist International – not a fringe sect but the established voice of millions of organised workers throughout Europe and beyond – had unanimously warned the ruling classes of Europe:

“Let the governments remember that… they cannot unleash a war without danger to themselves. Let them remember that the Franco-German War was followed by the revolutionary outbreak of the Commune, that the Russo-Japanese War set into motion the revolutionary energies of the peoples of the Russian Empire, that the competition in military and naval armaments gave the class conflicts in England and on the Continent an unheard-of sharpness, and unleashed an enormous wave of strikes. It would be insanity for the governments not to realize that the very idea of the monstrosity of a world war would inevitably call forth the indignation and the revolt of the working class. The proletarians consider it a crime to fire at each other for the profits of the capitalists, the ambitions of dynasties, or the greater glory of secret diplomatic treaties.”

And in actual fact, within months of their own uprising, revolution really was raging throughout Germany, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Italy, France and elsewhere. As the British Prime Minister Lloyd George wrote in a confidential memorandum: “The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution.” The royal dynasties of Europe were rudely dethroned, as the Hohenzollerns and Habsburgs followed the Romanovs into oblivion. In Britain, growing militancy was displayed in the general strike on the Clyde, the great mutinies among the British forces in France, the Triple Alliance of trade unions, the adoption by the young Labour Party of a socialist programme (the famous Clause Four which was to define the party’s socialist aspirations for the next eighty years) and the mass Councils of Action which sprang up expressly to defend the Russian revolution and impede the intervention; councils which Lenin called “Soviets, in essence if not in name”.

The mass of participants in the Russian revolution understood that they were part of an international tidal wave. On the very day of the October revolution, the resolution of the Petrograd Soviet affirmed its conviction that “the proletariat of the countries of Western Europe will aid us in conducting the cause of socialism to a real and lasting victory”. In his classic eye-witness account, the American journalist John Reed recorded the common thoughts of working-class Petrograd insurgents on the streets: “Now there was all great Russia to win – and then the world!”

The historic proclamation made the next day to the Congress of Soviets ended with an explicit call to the workers of Britain, France and Germany to “help us to bring to a successful conclusion… the cause of the liberation of the exploited working masses from all slavery and exploitation”. Lenin addressed the delegates with the hope that “revolution will soon break out in all the belligerent countries”, and Trotsky warned that “if Europe continues to be ruled by the imperialist bourgeoisie, revolutionary Russia will inevitably be lost… Either the Russian revolution will create a revolutionary moment in Europe, or the European powers will destroy the Russian revolution.” Reed reports that “they greeted him with an immense crusading acclaim”.

He gives ample evidence of the extent to which these internationalist ideas had percolated through to the working population. He quotes a Red Guard who “plied me with questions about America… Are the American workers ready to throw over the capitalists?” He also quotes a soldier fresh from the front: “We will hold the fort with all our strength until the peoples of the world arise”, who then addresses Reed directly: “Tell the American workers to rise and fight for the social revolution!”

Reed continued:

“Something was kindled in these men. One spoke of ‘the coming world revolution, of which we are the advance guard’; another of ‘the new age of brotherhood, when all the peoples will become one great family’.”

Even the peasants – illiterate, superstitious, steeped for centuries in veneration of Tsarism and Russian orthodoxy – became inspired. Their heroine Maria Spiridonova addressed their congress days after the October revolution:

“The present movement is international, and that is why it is invincible. There is no force in the world which can put out the fire of the revolution. The old world crumbles down, the new world begins.”

The Bolsheviks knew that ultimately their only strength lay in the common class interest of workers everywhere. They granted autonomy and the rights of secession to all the nations of the former Great Russian Empire. They chose to suffer the humiliating terms of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany, ceding large areas of territory and provoking crisis within the party and a government split with their Left SR allies, rather than break the faith of the people and allow them to drift into the clutches of the White terror. They made open appeals for peace, renounced all claim to booty and annexations and published the secret treaties, to expose to the workers the real interests of the capitalist governments. Their supreme task was the foundation in 1919 of the Communist International, the world party of socialist revolution.

No one reading Lenin’s writings and speeches at the time could doubt the spirit of international solidarity pulsing through his veins and embodied in his every word. He emphasised that “without aid from the international world revolution, a victory of the proletarian revolution is impossible…We did our utmost to preserve the Soviet system under any circumstances and at all costs, because we knew that we are working not only for ourselves, but also for the international revolution.” In March 1918, he wrote that there could be “no hope of the ultimate victory of our revolution if it were to remain alone… If the German revolution does not come, we are doomed.”

He was even prepared to sacrifice the accomplished victory in backward Russia if that was the price to be paid for a successful revolution in industrial Germany. In an emergency debate in 1918 over whether or not to seek a peace treaty with Germany, Lenin had even said:

“If the German movement is capable of developing at once in the event of peace negotiations… we ought to sacrifice ourselves, since the German revolution will be far more powerful than ours… It is not open to the slightest doubt that the final victory of our revolution if it were to remain alone, if there were no revolutionary movements in other countries, would be hopeless… Our salvation from all these difficulties… is an all-European revolution.”

Civil war

Just as the Russian workers, soldiers and peasants understood that their revolution was doomed without international support, so too the world’s capitalists understood that the October revolution constituted a mortal threat to their own survival. Suddenly the rival powers that had spilt the blood of millions for the previous four years in the scramble for markets joined together in combined attack on their common enemy. Early in 1918, British naval forces landed in Murmansk on the flimsy pretext of “helping to defend the gains of freedom won by the revolution against the iron hand of Germany.” Within days they were in fact marching South on Petrograd, disarming the workers and shooting local Bolsheviks. In April the Japanese landed at Vladivostok, and an “Omsk All Russian Government” was set up – an alliance of Cadets, Mensheviks and SRs which, having no forces to rely upon other than Tsarist officers, was shattered after two months by a coup installing Admiral Kolchak as dictator. Meanwhile, Germany occupied the Ukraine in collusion with White Guard Generals Krasnov and Wrangel. While the Allies screamed that Lenin and Trotsky were “German agents”, Germany countered that “in the Bolshevist movement…the hand of England is seen. By these movements England has gained much, since owing to Bolshevik phrases and money the strike movement was called forth in the Central Empire.” The police mentality sees in social clashes only the malevolent plots of conspirators. Every major capitalist power, and many minor ones too, joined in the rush to smash the revolution. It was officially admitted, for instance, that “the North Western (Baltic) Government was organised by General Marsh in 45 minutes’ time.“

Soon the occupying forces had replaced their initial claims with the hackneyed pretext that they were assisting the “vast portions of the population struggling against Bolshevik tyranny.” Respectable British diplomats and officers on the spot, however, more sensitive to the mood of their subordinates, revealed the true situation. Colonel Robins of the British Embassy in Moscow telegraphed home in March 1918: “Know of no organised opposition to Soviet Government.” Kerensky’s revolt had been crushed in hours and in April the Don Cossacks mutinied, murdering the hated General Kornilov and driving their Hetman (Chieftain) Kaledin to suicide. Colonel Robins wrote: “Death Kornilov verified, this final blow organised internal force against Soviet Government.” The British secret agent Bruce Lockhart admitted: “I had little faith in the strength of the anti-Bolshevik Russian forces…The one aim of every Russian bourgeois – and 99% of the so-called ‘loyal’ Russians were bourgeois – was to secure the intervention of British troops (and failing British, of German troops) to establish order in Russia, suppress Bolshevism and restore to the bourgeois his property.” Colonel Sherwood-Kelly of the Siberian forces said, “I formed the opinion that the puppet government set up by us in Archangel rested on no basis of public confidence and support, and would fall to pieces the moment the protection of British bayonets was withdrawn.” General Gough recognised that “the Russians are determined to prevent the return to power of the old official classes, and if forced to a choice, which is what is actually happening at the moment, they prefer the Bolshevik Government.” Count Kokutsev, for the Whites, put it even more delicately: “Without intervention, we cannot get through, for, while the moderate element exists, it is not concentrated…” Meanwhile, the counter-revolution could hardly offer the people of Russia a very alluring programme programme; in the words of Count Kidovstev: “To start with, it is clear that you must have a military dictatorship, and afterwards that might be combined with a business element…“

The unspeakable atrocities of White Guards Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, Wrangel, etc., reflected the panic of a doomed elite. Wrangel boasted that, after shooting one red prisoner in ten, he would give the others the chance to prove their “patriotism” and “atone for their sins” in battle. Thus, most White soldiers were actually press-ganged Red prisoners. What crushed the White generals was not superior force of arms, but mass desertion, mutinies and constant risings in occupied areas (in Archangel, Ukraine, Kuban and elsewhere). The Red Army grew to become a militia of five million workers and peasants.

However, the Bolsheviks understood that their ultimate strength lay in the power of workers’ solidarity. The Socialist International had to its eternal shame betrayed its ringing call in 1912 for a European-wide general strike in the event of war. On the contrary: the members of its constituent parties found themselves instead in army uniforms, shooting at one another across the battlefields. Following the collapse of the international at its moment of greatest need, the supreme task was the urgent foundation of a new international: a world party of socialist revolution.

The revolutionary government granted autonomy and the right of self-determination, up to and including secession, to all the nations of the former Great Russian Empire. They made open appeals for peace, renounced all claim to booty and annexations and by publishing the Tsarist regime’s secret treaties exposed the real interests of the capitalist governments.

Once the intervention had begun, they greeted the soldiers of the invading armies – working-class conscripts exhausted by years of war – with leaflets published in all their languages, explaining that they had been sent by their bosses to crush a workers’ republic, reporting news of the revolution raging throughout Europe and appealing for active support. This had an immediate effect. Russia was starved of arms. At one point, only a small area surrounding Moscow and extending barely to Petrograd had been in the hands of the Red Army. But mutinies broke out in the British, German, Czechoslovak and other armies, and in the French fleet stationed off Odessa.

In Britain, the main contributor to the intervention, General Golovin reported on his negotiations with Winston Churchill in May 1919: “The question of giving armed support was for him the most difficult one; the reason for this was the opposition of the British working class to armed intervention.” The Trade Union Congress condemned the Siberian occupation in September 1919 – and Siberia was evacuated within days. In May 1920 workers on London’s East India Docks refused to load the “Jolly George” ship with hidden cachements of arms for Poland. Mass demonstrations were held throughout the country, and a joint meeting of the TUC, the Labour Party NEC and the Parliamentary Labour Party threatened a general strike unless the intervention was called off. The intervention stopped most abruptly, and the Red Army had no difficulty in clearing up the native Tsarist relics within a few weeks. At indescribable cost, for the moment the revolution survived. The capitalist chain around the globe had been broken; the world revolution had begun.

Retreat and Reaction

It was at its weakest link that the imperialist chain had snapped. The most revolutionary working class in the world had taken power earliest in a country of age-old backwardness, with little industry, low productivity, long hours, mass illiteracy and a per capita income about one tenth of that of the USA. Less than 10% of the population were wage earners, and a far smaller proportion of heavy industrial workers.

Three years of savage civil war had aggravated conditions still further. In 1921 industrial production was down to one-ninth of the 1913 figure, and agricultural produce had slipped below the pre-1900 level. Seven million homeless waifs roamed the country, the people were starving and the peasants, thirsting for private land and fair prices, were becoming restive once the immediate danger of Tsarist restoration had been removed. The country had been forced to the stark emergency restrictions of War Communism – “Communism in a besieged fortress”, as Trotsky described it. Grain requisitioning at bayonet point, famine which brought in its wake cases even of cannibalism, malaria, over-hasty nationalisation, payment in kind, militarisation of labour, and the scarcity of finance, technical expertise and spare parts – this was the terrible price paid to save the Soviet republic. Their country was already steeped in age-old backwardness, with only pockets of industry, low productivity, long hours, mass illiteracy and a per-capita income about one tenth of that of the USA; but by the time they emerged from three years of civil war and foreign armed intervention, Russia was plagued with mass starvation, deadly epidemics, a desperate scarcity of finance, technical expertise and spare parts. Years of civil war and unremitting hardship had sapped the energies of the generation of October.

In such barbaric conditions, what prospect could possibly exist for the flowering of a democratic socialist civilisation? What is surprising is not that the revolution suffered gross, hideous, monstrous distortions, and survived as a grossly mangled caricature under the jackboot of a vile ruling clique… but that it was not immediately overrun and crushed underfoot by a victorious imperialism.

As soon as the exigencies of the civil war had ended, the hard-pressed peasantry revolted. At Kronstadt – formerly the rock-solid proletarian fortress of the revolutionary sailors – a disaffected body of newly conscripted peasants drafted from the rear mutinied. Riots broke out. So critical was the danger to the revolution that the tenth party congress in March 1921 was compelled to resort to the emergency expedient of temporarily forbidding factions within the Party – a measure quite unprecedented, even at the crucial moment of the October Revolution itself, when even dissident members of the Bolshevik central committee were able with complete impunity to campaign openly against its decision to call the insurrection.

Lacking a Bolshevik leadership steeled in struggle, the revolutionary wave which swept Europe finally subsided. The failure of the German Revolution in 1923 marked a decisive turning point. Victory in a socially and industrially developed country could have come to Russia’s rescue. In a state of retreat, isolation and hostile encirclement, bitter concessions to foreign companies, native entrepreneurs and a privileged intelligentsia became unavoidable.

Bolshevism and Stalinism

Another stock vilification of the revolution is the insinuation that it was Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks who had paved the way to the monstrous excesses of Stalinism. Once again, this is standing the truth on its head.

It was a fundamental principle of Marxism thatthe state itself was a barbaric relic, an instrument of class oppression which would begin to wither away from the very inception of the workers’ dictatorship. “Government over people” would be superseded by the mere “administration of things”.

Once the revolution found itself stranded within the confines of a backward semi-feudal Russia, how was this principle to be applied? In such conditions a smooth transition to a classless and stateless society was inconceivable. That’s precisely why Lenin and Trotsky placed the utmost priority on the urgent spread of the revolution to the more developed Western countries. But even in Russia, until foreign intervention had imposed the exigencies of “war communism”, the Bolsheviks enforced the strictest measures to stand guard against bureaucratic encroachments, including all those principles of workers’ democracy enacted by the workers of the Paris commune in 1871 and subsequently underlined by Marx. These were:

* no standing army, but the armed people;

* election of all officials by the workers’ organisations with direct right of recall;

* no official to receive a wage above that of a skilled worker;

* popular participation in all administrative duties;

* direct management and control by soviets (“When everybody is a bureaucrat, nobody is a bureaucrat“)

It is significant that when a communist regime briefly held power in Bavaria, Lenin’s first piece of advice was to introduce a seven-hour working day, to give every worker the opportunity to participate in administrative duties and check incipient bureaucratism.

But didn’t the Bolsheviks suppress rival parties? No! The first government established by the October revolution was actually itself a coalition of two parties: the Bolsheviks and the Left Social Revolutionaries (representing the poor peasants). At first even the capitalist parties (apart from the fascist Black Hundreds) were left free to organise. It was only under conditions of civil war and armed attacks by saboteurs and counter-revolutionaries that the Bolsheviks were compelled to impose an emergency temporary ban on other parties.

However, the working class was ruling in conditions of weakness and exhaustion. Already a tiny section of the population, it had been decimated by the civil war, the intervention and the famine, in which another five million people had died. It had to work long hours in excruciating conditions in the effort to reconstruct a devastated economy. Vile elements were crawling out of the crevices once the harsh regime of “war communism” had been replaced by a New Economic Policy, under which painful concessions had been wrung out of the government permitting a limited licence to private entrepreneurs. Worse still, in the extreme conditions of a backward and isolated Russia, there was no alternative but to enlist the services of the administrative personnel of the old Tsarist regime, luring them back by conceding to them a relaxation on the limit to their payment to allow a maximum wage differential of four to one; a concession frankly admitted by Lenin to be “a capitalist differential“. That is what Lenin meant when he complained that “we still have the same old Tsarist state machine today, with a thin veneer of socialism spread on top.”

Demoralised at the isolation of their revolution, nauseated by the antics of the “NEPmen” – speculators, kulaks (rich peasants), profiteers and black marketeers – and taunted by the return of a triumphant bureaucracy, it is hardly surprising that the Russian working class fell under the darkening shadow of a new form of despotism.

In such conditions, the party drowned in a cesspool of careerism. It was the sly and ambitious mediocrity Stalin (previously described as a “grey blur”) – a perfect personification of the resurgent bureaucracy – who surreptitiously accumulated more and more administrative power into his own hands.

Speechless on his deathbed after an unsuccessful assassination attempt and subsequent strokes, Lenin conducted a desperate struggle to the last against Stalin and the emboldened bureaucracy he represented. Increasingly aware of the powerful machine he was constructing, the blatant growth of careerism and corruption, and even the deception and intrigue he personally suffered at Stalin’s hands, Lenin broke off all relations with Stalin, formed a “bloc against bureaucracy” with Trotsky and sent a testament to the Party Congress urging Stalin’s removal from his post, which was suppressed. Lenin’s widow Krupskaya commented as early as 1927: “If Vladimir Ilyich had been alive today, he’d be in one of Stalin’s jails.”

Stalin did not create the reaction – he was its most lethal expression, and once created, he prolonged it. Bureaucratic degeneration was inevitable, given the isolation of the revolution and the weakness of the working class. It led Stalin inexorably along the road to the murder of all his comrades, the enslavement of the Russian working class, and the outright betrayal of the world revolution. The shrewd Georgian proceeded pragmatically, taking the line of least resistance at every turn; and this made him as ideal a focus for the Soviet bureaucracy as Lenin and Trotsky had been outstanding leaders of the revolutionary working class. The nonentity who had hypocritically donned the mantle of Lenin was to transform himself not into a revolutionary leader but into an Oriental despot.

To create a society founded on the principle “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need,” it must have at its disposal highly developed technological resources capable of providing for the needs of all. Where there is shortage there is inequality. Marx had said: “A development of the productive forces is the absolutely necessary practical premise [of socialism] because without it want is generalised and with want the struggle for necessities begins again, and that means that all the old crap must revive.” When a policeman is needed to control a food queue, as Trotsky explained, he will always see to it that he eats first and best. In the peculiar circumstances in which the revolution was isolated for a whole period to backward Russia, the state, far from withering away, rose to domination over the masses. For the workers, the only solution was the world revolution. For bureaucrats with a stake in the status quo, it was “socialism in one country.” Their privileges and power were after all secure.

Its relevance today

History has seen countless working-class uprisings: the Paris Commune in 1871, Germany in 1918-23, Barcelona in 1937, France in 1968 and many more. Russia in 1917 remains an inspiration, irrespective of the deformities which ultimately crippled it. It remains a historical testament to the truth that another world is possible.

And now more than ever, another world is necessary. In every continent today, a new generation is waking up to the reality that the only future it faces under capitalism is one of poverty, homelessness, hopelessness, discrimination, environmental destruction and war. Millions of people are in revolt, casting around for alternatives, sometimes seduced by false demagogues, but increasingly determined to find a road to change. Those commentators who used to scoff at the idea of revolution are today falling silent. In a recent Greek opinion poll, 33% called for “revolution”. And last year in the USA, 54% of respondents voted yes to the idea of a “political revolution to redistribute money from the wealthiest Americans”. That included 68% of Afro-Americans, 65% of Hispanics, and 68% of 18-29 year-olds.

It is time to rescue the Russian revolution from the history books and return it to its rightful place as a guide to action.