By Raphaëlle O, PCF Paris

The immediate cause of the Russian Revolution of 1917 was the devastating impact of the First World War on Tsarist Russia. It began on February 23rd, (or March 8th according to the Western European calendar), on International Women’s Day.

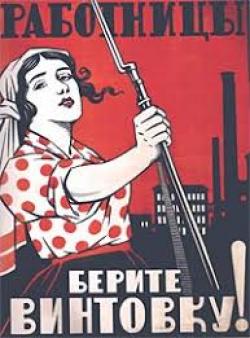

Hundreds of women workers in the Vyborg district of Petrograd walked out of the textile mills, going from one factory to another demanding that the workers – men and women – should join the strike. Here and there, they forced their way into the factories, and insisted that all the workers follow them out of the gates. The police attacked them. They fought back, throwing sticks and bricks. They felt they had nothing to lose. Working twelve and sometimes up to sixteen hours a day in the dirt and noise of the mills, heavily exploited and harshly treated, desperate for bread and other basic necessities, their lives had become intolerable.

The women demanded bread, but not only bread. The characterisation of the movement as being “spontaneous” is not really correct. Yes, the women were pushed into action by suffering, but this was not blind, unthinking rage. These women fully understood the cause of the problems that affected them. The demands for food and higher wages was mixed in with others with a far-reaching and revolutionary content: “Down with the Tsar!”, “Down with the war”!

These women knew that if the movement was to have any chance of success, they would have to engage thousands of other workers in the struggle. They also knew they had to win the active support of the soldiers. The lessons of the beginnings of the earlier revolution of 1905 – which was also provoked by a disastrous war, against Japan at the time – were in their minds. On January 9th, 1905, peaceful demonstrators had been pitilessly shot down by the Tsar’s troops. These two tasks: spreading the strike and winning the soldiers, went together. The soldier who refuses to obey orders and joins a revolt is punished by death. To win the soldiers to the cause of the people, they must be convinced that this was not just an episodic struggle, after which, when the clamour dies down, the old order will still be standing. In that case, the generals would still have the power to can take their revenge on the rebels. The soldiers have to be convinced that the movement will bring about fundamental change. This was the challenge the women workers faced in those first few days of struggle.

In his remarkable History of the Russian Revolution, published in 1930, Leon Trotsky wrote : “A great role is played by women workers in relationship between workers and soldiers. They go up to the cordons more boldly than men, take hold of the rifles, beseech, almost command: ‘Put down your bayonets – join us!’ The soldiers are excited, ashamed, exchange anxious glances, waver; someone makes up his mind first, and the bayonets rise guiltily above the shoulders of the advancing crowd.”

This role was indeed of vital importance. Through their understanding of what was necessary for the success of the struggle, through their audacity and their inspiring courage, the women of Petrograd had provoked a massive movement. Even on that first day, some 100,000 workers joined the strike. The numbers grew day by day and within just five days, the Tsar was forced to abdicate.

This first revolution, which overthrew the monarchy, would have to be completed by another, several months later. The soviets, which were democratic assemblies of workers’, soldiers’ and peasants’ deputies formed during the February strikes, would then take state power into their own hands. This would not have been possible without the political leadership of the Bolshevik party and of outstanding revolutionary leaders such as Lenin and Trotsky. In the months between these two revolutions, women workers and militants did not fall into the background. They were to play an important role during at each new stage of the revolutionary process.

At the time of the revolution, Russia was still a predominantly peasant society. Serfdom had been abolished in 1861, but this historically progressive development had mainly benefitted the wealthiest and most powerful landlords and capitalists. At the same time, it created a huge mass of landless and impoverished peasants. The desperate position of these poor peasants – living “from hand to mouth”, leading precarious lives and dying early in filthy hovels – was particularly hard on the women. Their legal status was one of subordination men. They were burdened with back-breaking labour in the fields, the endless drudgery of domestic chores and the mortal danger – both to mothers and infants – of childbirth. Even more than in the towns, women in the rural Russia could expect to be regularly beaten and mistreated.

However, in the decades before the First World War and the revolution, Russia had undergone major social and economic changes. Production of oil, coal and iron were rapidly increasing. Railways linked up distant cities. Modern industrial techniques and big factories were transforming the towns and cities, and large numbers of women were drawn away from the rural areas and towards an urban environment. The new machinery and the intense exploitation led employers to look for cheap and “docile” workers. They recruited women from rural backgrounds with this in mind. Hundreds of thousands of women moved away from the moral and intellectual stagnation of the villages to work in the factories, or else as servants, shop-girls and nurses in the towns. The textile industry (cotton, wool, silk), employed mainly women. Many women found jobs in ceramics, or in paper mills.

However, the employers’ hope that women workers would prove to be more docile than their male counterparts proved to be largely mistaken. In the 1890s, a number of important strikes involving women workers took place in the textile industry, and the many accounts we have of the 1905 revolution show that women workers took an active part in the events. Strikes took place in many industries where women workers were preponderant, such as textiles, tobacco and laundry services.

The 1914 war, which drained massive numbers of males from both town and country, had a major impact on the condition of women. In 1914, Russia’s standing army was close to 6 million soldiers. By the time of the revolution, the number of men mobilised had reached 12 million. About 2 million of them were slaughtered in the bloodbath. Another 4.5 million were wounded. This increased the burden on women, at home and at work. It also increased the numbers of women moving into towns and cities to work in industry. Statistics indicate that just over a quarter of the urban workforce was made up of women in 1914, but that they amounted to almost half (45%) of the workforce in 1917. Significantly, whereas the female contingent among metalworkers had only been 3% before the war, it had risen to 18% by the time of the revolution.

The increased social and economic weight of working class women led to greater political awareness and militancy. Working in factories had an effect on women that was similar to that of military service for the poor peasantry. Instead of suffering in isolation, just as it had organised the peasants into regiments, the war brought women together under common conditions of factory discipline and exploitation.

As would be expected in a culturally backward country such as Tsarist Russia, contemptuous and oppressive attitudes on the part of male workers were widespread. Even among the militants of revolutionary organisations, the political intelligence and capabilities of women workers were not always recognised.

The Bolsheviks were the only ones to have a clear revolutionary policy, and they took the problems of women very seriously in their programme and in their general aims. They stood for the complete overthrow of the old ruling class, of the landed aristocracy and the capitalists. They stood for an immediate end to the war on the basis of the publication of the secret treaties in which the great powers planning to divide the world among themselves. They stood for placing the factories and all the main levers of the economy under the control of the working people, through the soviets, trade unions and factory committees. They demanded that the land be under the control of the poor peasants, an end to all forms of national, cultural and linguistic oppression, and an end to the power of the Church. They declared that religion was a private matter of conscience, and should not be used as an arm of the state for the purpose of justifying oppression.

This audacious revolutionary policy opened up the perspective of a radical improvement in the lives of the working people. By contrast, what hope could there be for change if the war was to continue and if capitalists, princes and high priests would continue to rule? No matter how many “feminist” radicals were to be found in the ranks of the more moderate – that is to say, pro-capitalist – parties, concretely, they could offer little or nothing to working class women.

Over the tumultuous months which separated February from October, the Bolsheviks won the support of a large majority of the workers and soldiers in Petrograd, Moscow, and elsewhere. The soldiers – and the entire people – wanted an immediate end to the senseless slaughter of the imperialist war. After the victory of the soviet uprising led by the Bolsheviks in October, the new revolutionary government set about laying the foundations for a new social order. They knew the revolutionary regime could not survive unless the revolution spread to many other countries. Counter-revolutionary forces would try to destroy the revolutionary government by all possible means.

In the midst of so much backwardness and the ravages of war, Lenin, Trotsky, and the new socialist government could not overcome all obstacles immediately. They needed time, but did not know for how long they would remain in power. By publishing many new laws and declarations, they strove to indicate, to the workers of the world and to future generations, the kind of state and the kind of society they wanted to build.

The laws in relation to the family and women are particularly instructive. The old form of religiously sanctioned marriage was abolished and replaced by a simple civic registration procedure. Divorce was to be immediately granted on the request of either partner. It was not necessary to provide a reason for the request. Men and women were declared to be completely equal in all respects. A woman’s property and money was her own, to use as she pleased. Soviet Russia gave the right to abortion on demand, and was the first country in the world to do so. The distinction between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” children was abolished.

Given the failure of the revolutions in other countries, the revolutionary soviet democracy did not and could not last. As Lenin and Trotsky had understood, unless the revolution was victorious in other countries, the working class could not remain in power, especially in such a backward and ravaged country as Russia. The bureaucratic degeneration of the regime, which led to “Stalinist” dictatorship and then finally, much later on, to the restauration of capitalism. But this does not in any way diminish the tremendous historical significance of the 1917 revolution, in which working women played such a momentous part.