By Barbara Humphries, Ealing Southall CLP (personal capacity)

1918 saw the end of the First World War and major political change sweeping across Europe. In Russia, the old regime was overthrown by a revolution. In Britain, there were strikes across the country for shorter working hours and the Representation of the People Act increased the electorate threefold. For the first time all men over 21 got the vote, and some women over 30. The majority of those newly enfranchised were working class. Although Liberals and Tories had their eyes on the working-class vote, the Labour Party was to benefit most from this extension of the electorate.

Ahead of the 1918 General Election, the Labour Party adopted a new constitution. This allowed for an individual membership. Before this, the Labour Party (originally the Labour Representation Committee, founded in 1900) had been an electoral alliance of trades unionists and socialist organisations such as the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the Fabian Society. The creation of divisional Labour Parties in all parliamentary divisions, allowed the Party to campaign across the whole country, not just in the industrial heartlands, like mining constituencies. The Party could now organise in areas where the trades unions were weak, attracting women members, with its policies on housing, public health and welfare reform.

Nevertheless, trades unions were still affiliated to the Labour Party at a national and local level, and played a large role in financing the party, providing many of its local activists. An important part of the new constitution was Clause IV, Part Four.

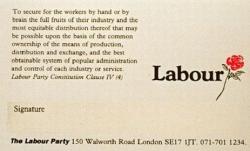

‘To secure for the workers by hand and brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.’

This was the first time that the Labour Party had committed to a specifically socialist programme. In contrast to the socialist parties in continental Europe, Labour had been set up as a party of the working class, to represent trades unions in Parliament. The socialist ILP had been a component part of this, but the Marxist Social Democratic Federation declined to affiliate. Keir Hardie always said that as a working-class party, inevitably the Labour Party would adopt a socialist programme and he urged the SDF to reconsider their position.

In 1917 the Co-operative Party was founded to provide political representation for the Co-operative Movement. It had the aim of common ownership, which it hoped would replace the capitalist middleman and provide consumers with a better deal. Clause IV, Part 4 was deliberately vague in what form ‘common ownership’ should take. This made an early alliance between the Labour and the Co-operative Parties possible, as they had similar political aims, representing the working class as workers and consumers, the latter aimed at women voters in particular. Reference in the Clause to the workers ‘by hand or by brain’, signified the diverse nature of the working class, not just coal miners and textile workers, but office workers, teachers and engineers.

In the 1918 General Election the Labour Party gained the second highest number of votes, and became the main opposition in Parliament, having withdrawn from the wartime coalition government. The leaders of the two established parties, the Liberals and Conservatives, were outraged that this new party had claims to win the working-class vote, in a country where manual workers were a majority of the population.

They dubbed Labour as ‘the socialist menace’, and resolved to join forces to defeat it. However, Lloyd George for the Liberals and Winston Churchill (now a Conservative) could not agree on which of them was best placed to take on Labour! The British ruling class were also divided over free trade and protection, the Conservatives supporting tariff reform, the Liberals ardent free traders.

It was this division which led to the first Labour Government in 1924, although it was not the largest party in Parliament after the 1923 General Election. The Conservatives were the largest party, but advocating tariff reform, their Kings Speech was voted down by Labour and Liberal MPs, and early in 1924 Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald was asked to form a government.

In spite of Clause IV, there was not much commitment to socialism in the first two Labour Governments in 1924 and 1929-1931. In both cases, the governments were dependent upon the Liberals and no significant nationalisation of industry was proposed, although nationalisation of the coal mines was Labour Party policy. However, the Minister for Health in 1924, left wing Clydeside MP, John Wheatley, was able to increase government subsidies for public housing across the country. This allowed local Labour councils in particular to continue building council estates in the interwar years, in some cases, as with the London County Council, providing a model of what public ownership could deliver.

It was not until 1945, that the Labour Party set out the aims of Clause IV, Part 4 in its manifesto, Let us Face the Future. It sold over a million copies, outlining a programme of nationalisation of Britain’s staple industries, coal and transport, and public utilities like water, gas and electricity, as well as plans for universal welfare, or better, for a welfare state, as well as the National Health Service.

In the 1945 General Election Labour was elected with a landslide majority and overwhelming support from the British electorate. This was after five years of war, in which substantial public control had been put in place by the wartime coalition government. No-one wanted a return to the days of mass unemployment, which had affected large parts of the country in the 1930s. The Bank of England was also nationalised for the first time. In other countries, government ownership of the national bank had been the policy of centre-right governments, as in France. The British Conservatives however had a deep attachment to private ownership, with their heads stuck in the 19th century.

Public ownership did not achieve all that had been hoped for. It was a top down approach. The old owners were heavily compensated and even sat on the boards of nationalised industries. There was no direct worker representation. But it was a new beginning, and the Tories, when returned to government in the 1950s, did not try to undo Labour’s reforms. There was no wide-scale privatisation of public utilities until the 1980s, when most of them were privatised in an alleged attempt to create a ‘people’s capitalism’ by the Thatcher government. Everyone could be a shareholder, or so it was argued. In fact, very few of those who bought or were given shares in the 1980s hold them now. Council houses were sold, many of them now are in the ‘buy to let’ housing market – not owned by occupiers at all. Councils were not allowed to build houses to replace the ones they had sold – hence the housing crisis that we face today. Perhaps the worst example of privatisation however, and the most unpopular, was that of the railways. That was carried out by the government of John Major in the 1990s.

After four election defeats for Labour, Tony Blair, as leader, set out the mission of ‘modernising the party’. This included getting rid of Clause IV, Part 4. This was not the first time that a Labour leader had set out to do this. After the general election defeat of 1959, Hugh Gaitskell had also tried to get rid of Clause IV, but it had been decisively rejected by the November Labour Party conference in 1959. In what turned out to be his final public speech, left winger Nye Bevan made an impassioned speech to retain Clause IV

“What are we going to say, comrades? Are we going to accept defeat?….Are we going to send a message from this great labour movement, which is the mother and father of modern democracy and modern socialism, that we in Blackpool in 1959 have turned out backs on our principles because of a temporary unpopularity in a temporarily affluent society?”

In 1994 Blair, in spite of opposition from much of the party membership, was successful. He wanted to convince the neo-liberal establishment, that a Labour Government would not reverse the policies of the Thatcher years and would be ‘business friendly’. In government, Blair and Brown extended Private Finance Initiative (PFI) deals, allowing the private sector to run public services.

All was going swimmingly, or so it seemed. Then came the world financial crisis (2007/8) and the collapse of Northern Rock and the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS). These two banks were bailed out and taken into public ownership, with the tax payer footing the bill. One of the private rail franchises, on the East Coast Line, also fell into the public sector. The private sector was no longer dependable. To let the banks go to the wall would have led to a recession, possibly deeper than in the 1930s. The Tories, however, were not slow to blame the Labour Government for economic incompetence and have used the resulting black-hole in public finances, to implement the deepest cuts to public services since the 1930s.

The collapse of Carillion makes a re-evaluation of Clause IV very timely. Yet again we have seen the failure of a profit-making private company to deliver public services. Labour members now may well ask, why did they get rid of Clause IV? In the 2017 General Election, Labour gained a lot of support for a manifesto calling for re-nationalisation of the railways and public utilities. Now it is also time to take back the PFI contracts, as advocated by the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, John McDonnell, and dust off the basic outlines of a socialist policy as it was envisaged in Clause IV.

January 21, 2018