By Ray Physick

The Durham Miners’ Gala is and has been one of the most important gatherings in the labour movement calendar. The great historical significance of the Gala and its origins in the decades-long struggle of the miners, over a century ago, is explained in this article, first published in the newspaper, Militant, in 1983.

Throughout the 1800s, the miners of County Durham fought many battles with the coal owners. The miners’ organisation came out of these struggles, often violent, often leading to defeat, or leaving militants imprisoned or blacklisted by the coal owners. The 1832, 1844 and 1869 strikes stand out from the many.

When the annual Gala began, it was a reflection of the fact that the union which on previous occasions had been smashed by the employers, was now of a firm footing. And how better to celebrate a strong union than by having an annual political and social gathering!

Conditions in the 1800s were grim. Long hours combined with bad conditions at home and at work. At this time, boys went down the pit at the age of 6 and worked up to 17-18 hours a day. There were no schools or provision to develop young people and any attempt to provide young miners with a basis of education was jumped upon by the coal owners. The coal owners did not want the miners to have any semblance of independence.

The main form of repressions found expression in the hated Yearly Bond. At each pit, the coal owners drew up a bond which tied a miner to a particular colliery owner for a year. If the miner attempted to leave the area or to find alternative work, they would be charged and imprisoned. In effect, the miner was a bonded serf and was forced to tolerate the bad conditions of work and pay.

Strikes arose continuously over the bond and the conditions laid in it. The first important strike came in 1810. The men refused to bond and were duly locked out. Delegates from different collieries held frequent meetings both in Durham and Northumberland. The aim was to unite the men – by no means an easy task in those days.

Activists hunted

The activists were hunted from place to place by the owners and magistrates, assisted by the military, and large numbers of miners were committed to prison. When Durham prison was full, the Bishop of Durham offered his Christian charity by opening his stables as a stand-by prison. The men were guarded by the Durham Volunteers and Special Constables and later by the Royal Militia.

The strike, which lasted seven weeks, ended in partial victory. Binding time was agreed on April 5 and was negotiable each year. Previously, the coal owners had simply laid down their own terms. But negotiation gave rise to many conflicts in areas.

It was not until 1830, however, that discontent brought the miners to organise better, when the miners of Durham and Northumberland joined together in one large union which was called ‘Hepburn’s Union’ after its leader Thomas Hepburn. By 1831, the miners felt strong enough to take on the coal owners. When the bond expired on April 5th 1831, they struck to a man for better wages and shorter hours.

An early feature of these miners’ organisations was the mass meeting: often bringing together 25,000 or more miners. Every colliery would march to the field, bearing its banner and some had bands. The tradition of the Gala was being set. Whenever they were going forward, the miners came together in a show of strength and solidarity.

The 1831 strike again saw an advance for the miners. They secured better hours, particularly for boys who now worked 12 hours a day instead of a working day almost without limit. The coal owners were aware, however, that allowing this new union, a new union prepared to campaign in the areas, to gather strength, would threaten their profits. Consequently, they began to hire mercenaries with the object of driving strike leaders out of the locality. With the ground set, the coal owners refused to bind any men belonging to a union. The mean stayed united and once again struck to a man.

The employers recruited scabs. The scabs needed homes, therefore, the miners were evicted from their tied homes with great brutality. By using scabs, the military and general repression, the 1832 strike was crushed and the union beheaded. Hepburn, the major leader, was also broken. At first, he could not get a pit job and sold tea about the colliery districts to sustain a living. Later, he agreed to renounce the union and found employment as a miner. The union being broken, the coal owners commenced making reduction after reduction in their wages.

Every July, on the Gala day, delegates from miners’ lodges visit the grave of Thomas Hepburn in Heworth, Gateshead, where wreaths are laid and tributes are paid to Hepburn’s work a century ago.

The next major union of the miners arose out of the 1842 General Strike. This was a decisive turning point for the British working class. It marked in clear terms, in Engels’ words, the “decisive separation of the proletariat from the bourgeoisie.” After 1842, major sections of the working class began to move in the direction of forming truly national unions. The most powerful of these was the Miners Association of Great Britain (MAGB). The objects of this union were to “bring about the lessening of hours of labour, to secure themselves a fair remuneration for their labour, to agitate for government interference and for inspectors to be appointed to enforce laws enacted for the protection of the men.”

Centralised union

The coal owners immediately saw the Association as a great threat to themselves. Here, the leaders of the Miners’ Association showed a weakness, despite the lessons of the past, imagining they could develop the union without interference from the coal owners. The Miners’ Association was both a centralised and a democratic organisation. The backbone was made up of its lecturers (full-time officials) who were the key in developing the organisation at grass roots level. Often, persecution by the coal owners was so intense that merely to hold union membership was enough to get a miner the sack and eviction from his cottage. So men had to be discreet about expressing their beliefs. It was only the lecturers, with no mining jobs to lose, who could come out in open defiance of the masters.

By the power of their personal example, lecturers banished timidity and imbued workers with the will to resist. But at the same time, they were expected to devote eleven days a fortnight to the Association and were required to give an account of their labours. Lecturers were also subject to recall by the national delegate meeting which met every six months.

The July 1844 conference instructed each lecturer to: “collect every kind of information appertaining to the interests of the miners in particular and to society in general, especially statistics regarding the wages of labour, the habits and conditions of working men and all those causes that mainly affect the present state of things, and when meeting with men to use the simplest means for the purpose of digesting the information acquired and to mature the plans laid by the Association” (Miners Advocate, July 1844)

The sinews of war

As with all working class organisations, the union relied upon the sacrifices of the workers themselves. The following is from a circular to the union branches: “Mr Roberts is determined to break down tyranny under which you have been so long groaning: no effort or energy on his part will be spared; his labours have already been successful. But it is you who must furnish the sinews of war!! Much that ought to be done is now prevented by want of money. This ought not to be.”

That is roughly the sort of organisation that the owners had to contend with. They prepared themselves to smash such a dangerous organisation of the working class. The union’s national conference had voted against a strike as premature, but the owners of Durham and Northumberland forced the hand of the miners by offering worse conditions. They hoped to use this as a position of strength to weed out prominent union men.

On April 5, 1844, the miners refused to bind and every pit came to a standstill. At a meeting of 35,000 miners at Shildon Hill, the miners resolved, “this meeting avows its intention and determination to procure individually and collectively a better remuneration for their labour than has heretofore been paid and to abstain from working until such remuneration be obtained.”

As in 1832-3, the coal owners used the tactics of blacklegs and evicting whole families from their homes to make way for the scabs. The owners were ruthless. Pregnant women, bedridden men and women, children in the cradle, were all remorselessly turned out.

At Pelton Fell colliery, near Chester-le-Street, the owners turned out an 88-year old blind woman on the streets. The evicted families had to make do with the homes made out of chests and furniture covered with canvas. On the instructions of their executive, the miners were constrained from defending themselves and therefore could not use effective picketing to stop the scab from going down the pit. They hoped to show by moral example how good their case was.

Weak tactics

But these weak tactics only emboldened the owners. The Marquis of Londonderry, for example, ordered tradesmen on his estate to refuse credit to the strikers – to starve the miners back. By the end of July, almost every colliery in the two counties had commenced work with imported scabs. The resolve of the miners was beginning to weaken.

By mid-August, after 18 weeks on strike, starving and destitute, great numbers of men began to break away from the ranks of the union and return to work. Many of the strike leaders never found work again. The union was effectively broken. In the words of one coal owner, “the bond enables us to get rid of the bad characters as they show themselves.” The Miners Advocate declared, however, “As capital can alone successfully invade through a division in its ranks, it is clear that nothing short of all Labour united can effectively defend it.” The miners’ paper was saying that the miners would return.

After 1844, a boom occurred in the economy. Many of the evicted miners found work as coal production expanded. The period of boom enabled the wounds of defeat to heal. But by the mid 1860s, the coal industry began to flounder again. As a result, the owners once again went for the wages of the miners.

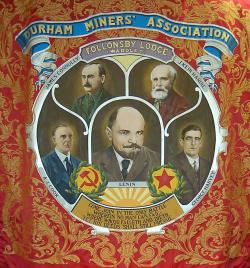

In 1866, 1867 and 1868 material reductions were made in wages in various parts of Durham. In 1869 a general reduction took place throughout the whole of Durham. Strikes occurred. Out of these struggles, the lodges of Thornley, Trimdon and Monkwearmouth bonded together and laid the foundation of what soon became the Durham Miners’ Association. By May 1870, the union was firmly established with 216 lodges representing 140,000 men.

In early 1872 more disputes broke out over the yearly bond. This time, however, the miners secured its abolition, a recognition by the owners that this time a struggle over the bond might not be won

The first Gala, in 1871, representing upwards of 200 pits and 150,000 miners, was a demonstration that miners’ unity was established and was here to stay.

July 6, 2018

First published in Militant, July 15th, 1983.