By John Pickard, Brentwood and Ongar CLP, personal capacity

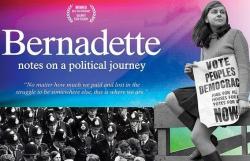

Brentwood and Ongar Labour Party held an excellent film night last week, showing Bernadette, Notes on a Political Journey, followed by an excellent political discussion. The film is an account of the tumultuous political career of Northern Irish activist Bernadette Devlin-McAliskey and it conveys marvellously the volatile sectarian environment in Northern Ireland in which she rose to power. The film night was attended by the director, Lelia Doolan, which was an additional bonus.

Bernadette Devlin, as she was then, was a leading activist in the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement and later the Peoples’ Democracy and she was first elected MP for Mid-Ulster in 1969 as a 21-year-old student.

The film contains a wealth of archive footage from the period of Devlin’s career, particularly that crucial period in the late 1960s, including the Civil Rights marches, the Battle of the Bogside in Derry, the foundation of Peoples’ Democracy, the introduction of internment without trial and Bloody Sunday, when British paratroopers shot thirteen unarmed demonstrators in Derry.

This was a period in which I and many other Labour Party Young Socialists were inspired by the heroic struggles for civil and equal rights and yet at the same time appalled at what seemed to be an inexorable drift towards sectarian politics. Prior to this period, the Northern Ireland Labour Party stood candidates in elections and could potentially offer a class alternative to the traditional parties. It gained 26 per cent of the vote in 1962. But after this period – and right up to this day – the only choices on offer at election time are those parties perceived to be (whatever their small print might say) as Protestant or Catholic.

This film is a biopic of the life of a passionate and sincere socialist activist and is not a straightforward historical narrative. For those unfamiliar with the events – in the early period particularly – the exact chronology can be a little confusing. The historical material is also interspersed with extracts from a series of more recent interviews.

Nevertheless, for older activists in the movement, the newsreel footage of those days leaps from the screen like a living reminder of the intensity of that period. Who can forget the diminutive figure of Bernadette, a feisty third-year student who was not only a socialist but a natural orator, who blew into the House of Commons like a hurricane?

After Bloody Sunday, she strode across the Chamber of the House and slapped the Tory Home Secretary Reginald Maudling, an act for which she was banned for a long period from the House. There is footage of the interview she gave afterwards. Asked if she would apologise for her actions, she said she was only sorry she did not get him “by the throat”. A short clip of that marvellous interview can be seen on YouTube at: https://youtu.be/3EKx0wOFQP8

The Establishment detested Bernadette Devlin – not that she cared. Later, during the period of the H-block protests, there is more than a hint of collaboration between the British Army and those assassins who tried to kill her, pumping eight bullets into her. She survived, which is more than can be said about the other members of the H-block protest committee.

For a more complete view of that period of Northern Irish politics, it is worth reading around. The film has certainly stimulated this viewer into looking at the old documents, newspapers, pamphlets and books of the time. John Throne, who was an active member of the Strabane Young Socialists and who participated (with scores of other YS members) in the defence of the Bogside, has recently published a book, We’ll Take a Cup of Kindness Yet. In it, he described the invasion of the Bogside by sectarian bigots, assisted by the police. The Bogside uprising, which lasted five days in August 1969, was no “skirmish”. “Thousands of people participated, over 1000 people were injured in the fighting. Over 350 police sustained serious injuries. The Battle of the Bogside, as it came to be known, was a real mass uprising.”

Underlying the Civil Rights struggle that was to catapult Bernadette Devlin to national and international fame, was the blatant discrimination against Catholics in local government, particularly in Derry. John Throne writes,

“Derry was the second largest city in the North…the electoral boundaries were drawn so that if voting took place along religious lines the two-thirds majority Catholic population could only elect one third of city councillors…along with this religious discrimination there was class discrimination. In local elections only people with property could vote. Those who lived in local, publicly-owned housing could not vote. People who owned multiple houses could have up to six votes. In parliamentary elections there was the so-called business vote, which was only for those who owned businesses. These electoral laws affected Catholics as almost 90% of commercial property was owned by Protestant business people…an estimated one quarter of a million potential voters were prevented from voting in local elections…60% of these were Protestant.”

The tragedy of Northern Ireland was that the leadership of the official labour and trade union movement offered no class alternative that would have appealed to both sides of the sectarian divide. Protestant and Catholic workers suffered from unemployment, low pay and poor housing but the marginal advantages given to the former as against the latter were used by the ruling class to divide and rule.

Protestant working class switched off

The Civil Rights movement and its successor the Peoples’ Democracy, were not able to win footholds of support among the Protestant working class and despite their good intentions, were increasingly perceived as a ‘Catholic’ movement. One of the six points in the PD programme, mentioned in the film, was for fair placing on the waiting list for council houses. This might be a perfectly democratic demand in itself, but by undermining the tiny advantage of Protestant workers, it cut off any possibility of winning them. A socialist alternative, offering homes for all workers would have been a better option than ‘fair shares’ in the hardship queue.

John Throne made similar arguments in his book: “…with the privileges and power of the Protestant elite and the marginal privileges of the Protestant working class, it would have been hard to win Protestant workers to the civil rights movement under any conditions. But when the leadership of the civil rights movement fell into the hands of the Catholic nationalists and republicans, it was impossible.”

This is not the place for an extended socialist history of the last fifty years in Northern Ireland. Readers of Left Horizons must go back to the literature and read for themselves what was written at the time and come to their own conclusions. But I would recommend any Labour Party to show this film as an inspiring introduction to a discussion on the recent history of Northern Ireland.

The film, by the way, was the winner of the International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in Glasgow and the Best Feature Documentary prize at the Galway Film Fleadh. And even after paying for Lelia Doolan’s trip from Ireland to Essex, our event raised £350 for the Labour Party, and stimulated an excellent political discussion.

November 11, 2018

John Throne’s book, We’ll Take a Cup of Kindness Yet can be obtained here:

http://www.books.ie/we-ll-take-a-cup-of-kindness-yet-memoir-and-manifesto