By John Pickard

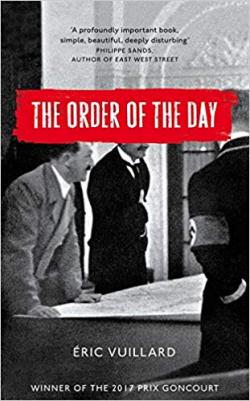

I read a review for The Order of the Day, by Eric Vuillard, in the Financial Times. It is a mixture of fiction and fact, set in the 1930s, in Germany and Austria, with cameo elsewhere, like in Austin Chamberlain’s house, where the British Prime Minister entertained the soon-to-be Nazi Foreign Minister, Ribbentrop. The book won the 2017 prestigious Prix Goncourt.

Contrary to the impression given in the Financial Times review (suggesting that the reviewer hadn’t read the whole book), the bulk of the book explores the actions of the Austrian Prime Minister in 1938, Kurt Schuschnigg. It documents real events but gives a fictionalised portrayal the hypocrisy and ultimately the complete indifference of Austrian right-wing politicians to the Anschluss, the forced unification of Germany and Austria under the Nazis.

But key episodes at the beginning and end of the book deal with another issue: the support given to Adolf Hitler by German big business magnates. It is a topic to which Vuillard has returned today. Speaking at the Hay Book Festival in May of this year, Vuillard expressed his concern about the rise of the extreme right-wing across Europe. Although history does not repeat itself, he said, looking at French politics today, he saw “similarities between certain situations that are worth of examination. They help our understanding of events, past and present. He cites the concentration of economic power, a growing lack of transparency as major decisions are made away from the public gaze, and a failed dialogue between the ruling classes and the general population.” (Financial Times review, May 31)

Nazis putting the squeeze on business chiefs

One of the key passages in the book describes a meeting in 1933 between Hitler and two dozen top industrialists, brought together to be tapped for money by the newly-appointed German Chancellor. Elections were about to take place – this was when Hitler was still consolidating his position – and the Nazis needed money for their propaganda and campaigning. Vuillard describes the demeanour of these businessmen – meek, subdued and deferential – and what they represented: “…these twenty-four men are not called Schnitzler of Witzleben, or Schmitt, or Finck, or Rostberg, or Heubel, as their identity papers would have us believe. They are called BASF, Bayer, Agfa, Opel, IG Farben, Siemens, Allianz, Telefunken. By these names shall we know them.”

By this time, within only weeks of having been appointed Chancellor, hundreds of Jews were already being rounded up and send to Dachau. Gangs of Nazi thugs, sometimes hundreds strong, were attacking socialist, communist and trade union offices and many thousands of labour activists were being taken off to Dachau. Yet it is worth recalling that even in the midst of this terror campaign, when the Nazis were taking violent control of the streets and neighbourhoods, they failed to get a majority in the election and the Socialists and Communists combined still got 12 million votes. It was the last free election until Hitler and the Nazis were overthrown.

Towards the end of the book, Vuillard outlines the benefits that had accrued to big business for having supported the Nazi election machine in 1933. Looking back in retrospect at these companies, he listed how they had used forced labour – slave labour – often from concentration camps in the Nazi era.

“…they did very well. The war had been profitable. Bayer took on labourers from Mauthausen, BMW hired in Dachau, Papenburg, Sachsenhausen, Natzeeithr-Struthof, and Buchenwald. Daimler in Schirmeck. IG Farben recruited in Dora-Mittelbau, Gross-Rosen, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Ravensbruck and Mauthausen and operated a large factory inside the camp at Auschwitz, impudently listed as IG Auschwitz on the company’s organisation chart. Agfa recruited in Dachau. Shell in Neuegamme. Schneider in Buchenwald. Telefunken in Gross-Rosen, and Siemens I Buchenwald, Flossenburg, Neuegamme, Ravensbruck, Sachsenhausen, Gross-Rossen and Auschwitz. Everyone had jumped at the chance for such cheap labour…”

Dickens and Zola or John Stuart Mill?

The book is a work of fiction mixed with facts, but Vuillard makes no allegation that the specific events he describes actually took place, at least in the exact way they are described. But we know that big business really did finance Hitler and the Nazis, so his portrayal of events is at least plausible and based on the political trends of the time. In any event, he argued at Hay, “Dickens and Zola are better guides to the realities of the 19th century than the likes of John Stuart Mill”. Perhaps this is true in relation to Mill, but on the other hand, he might also have mentioned The Conditions of the Working Class in England in 1844, by Friedrich Engels and other works by him and Karl Marx, which were certainly not works of fiction. They were as much a guide to the realities of the day as Charles Dickens or Emile Zola.

Vuillard’s book is quite a slim volume, at 130 pages, and hardly worth the £9.99 it costs new, but if you see it in a charity shop for a quid, it might be worth a read. Big Business did finance Hitler and the Nazis. In the end, they saw it as their only option to stave off a revolutionary movement by the German working class. But there are far better books out there that deal with the mutual link between business and the Nazis and far better books on the Anschluss.

June 12, 2019