By John Pickard

After coming across a review in the Financial Times of Varlam Shalamov’s two books of short stories, about his experiences in the Russian gulags, I decided to give them a go. I’m glad I did. The two volumes are a marvellous addition to modern political literature, although most of the short stories were written in the 1950s and 1960s. More to the point, they are much better and have much greater depth and insight than the books of his more celebrated contemporary, Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Shalamov’s books, newly translated into English (published by New York Review Books), are called Kolyma Stories and Sketches of the Criminal World, further Kolyma Stories. Each is composed of three collections or ‘cycles’ of stories, the longest over forty pages and many as short as two or three. Shalamov is a master of the short story genre, but what leaves a profound impression is the content of the works.

Impossible to ever get warm

Kolyma is a region in the far North West of Siberia, a frozen hell, where temperatures frequently go down to 50o or 60o below zero. There are no thermometers available, of course. It is only possible to gauge the temperature by how much it hurts to breathe and whether or not a gob of spittle will freeze before it hits the ground. It was here that Shalamov spent 18 years of his life, up against brutality, hunger, overwork, scurvy, lice, typhus and an utterly demoralising blank wall where for most people there would have been a ‘future’.

For days and weeks on end, Shalamov explains, it was impossible to get warm: whether working, eating, walking or sleeping. Frost-bite was ever-present. It was only possible, as he explained over and again, to live one day at a time. Many didn’t manage that, succumbing to hunger, cold, disease or the everyday brutality of the guards and other prisoners, especially the ‘non-politicals’ – common criminals, referred to as ‘gangsters’ – who were always favoured by the guards and the camp regime.

Lenin’s Last Testament

As the Stalinist bureaucracy began to establish and consolidate itself in the 1920s, its first target for rounding-ups and incarceration were the supporters of Trotsky. Shalamov was one of those. He was first arrested in an illegal print-shop in 1929, as he was helping to prepare the distribution of Lenin’s “Last Testament” which had been suppressed after his death, because of its denunciation of Stalin. That was the first of his three spells in the camps.

After the Trotskyists, all the former leaders of the Bolsheviks, one after another, were tried in the great ‘show trials’ of 1936 and 1937 and shot. Anyone with links to the ‘old’ Bolshevik Party (meaning 1917), no matter how minor, became a victim. Stalin drew a line of blood between his regime and the traditions of the October Revolution. The smallest sign of independent or critical thought was suppressed. Not only were genuine ‘dissidents’ arrested, but so too were hundreds of thousands who were not even involved in politics, arrested for no other reason than being denounced by some personal enemy or other.

All Russian prisoners-of-war sent to the camps on release

In the years before World War II, Stalin completely purged the officer corps of the Soviet armed forces, debilitating the country militarily by the time of the Nazi invasion. Later, after the war, anyone who had been captured by the Nazis – no matter that they may have fought heroically for the Red Army – was arrested and sent to the camps. The only well-organised break-out that Shalamov describes is one conducted by a group of battle-hardened Red Army soldiers who managed to organise themselves well enough to break out.

As Shalamov writes, “In the 1930s, arrests happened to people by chance. They were victims of a terrible and false theory that the class struggle would intensify as socialism became established. The professors, party workers, military officers, engineers, peasants and workers who filled the overcrowded prisons, had no particular virtues except, perhaps personal honesty or perhaps naivety – in short, qualities that made the punitive work of the “justice system” at the time easier rather than harder…they were neither enemies of the authorities nor state criminals, and when they died, they still didn’t understand why they had to die.”

Once denounced, the family would follow

Shalamov was a ‘political’, a prisoner held under the notorious ‘section 58’ for “counter-revolutionary activities”. His ‘crime’ was one of the worst, as it happened; his case file included KRTD, the ‘T’ standing for ‘Trotskyist’, counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activity. That one letter made a big difference and later on he was able to have it surrepticiously removed. Perhaps it saved his life.

Once having been denounced, family members would follow. In one story, Shalamov describes how a grandfather was denounced and both he and his son were shot. Even his 16-year-old grandson was given 10 years hard labour in Kolyma. So much were ordinary workers terrorised by the Stalinist apparatus, that getting a ‘tenner’ was thought to be a good result – it was better to get ten years in a camp, with at least a hope of coming back, than being put against a wall.

What constituted ‘anti-soviet activity’? As Shalamov says, no-one really knew. “Nobody needs to be told what constituted counterrevolutionary agitation outside the prisons in 1937. If you praised a Russian novel published abroad, ten year for ASA (Anti-Soviet Agitation). If you said that the queues for liquid soap were extremely long, five years for ASA.”

Samizdat publications amended his work

Shalamov began to write his stories when he eventually got out of the gulags, following the denunciation of Stalin by Kruschev in 1956. However, sometimes the early samizdat publications ‘improved’ the text of his stories without his permission. Later international publishers, like the New York-based, New Review (Novyi Shurnal) even cut out whole paragraphs. The new English edition of these two volumes, translated by Donald Rayfield, has at last kept to the original composition and integrity of the works, thanks to the translator’s access to all the original Russian manuscripts.

We have to ask the question as to why it is that Alexander Solzhenitsyn is so well known, but Shalamov is not? It must be because politically and stylistically, they are opposites. Solzhenitsyn, according to Shalamov, was playing “according to the rule book of Cold War cultural politics…Shalamov never disavowed the Soviet project”.

Shalamov remained an atheist and materialist

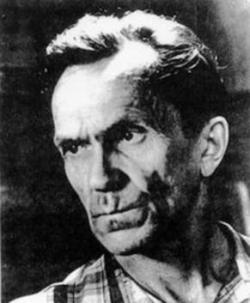

Solzhenitsyn embraced Catholicism and became a strident opponent of socialism and the very idea of a state-owned, planned economy, as Russia then was. Shalamov was the opposite. He was opposed to the monstrous bureaucratic apparatus of Stalinism, but he still embraced the idea of an economy that was state-owned. For the remainder of his life – he died in 1982 – he remained an atheist and retained a firmly materialist view of literature. He was anti-authoritarian for the rest of his life and had no time for the glamour of western literary ‘celebrity’.

Shalamov can be researched on Wikepedia, for anyone interested in his life. The two volumes of books on Kolyma are not short; the first is 740 pages, the second 540, but they are well worth the read. All things are relative: after Kolyma Stories, you will never feel cold in bed again.

February 19, 2020