By Mark Langabeer, Newton Abbot Labour Party member.

The second episode of the BBC Andrew Marr series on the making of modern Britain covers the period of the 50s and early 60s. The first episode ended with the election of Churchill in 1951. He was quickly replaced by Anthony Eden, described by Marr as being in the shadow of Churchill for 15 years.

Harold Macmillan described his last sighting of Churchill as Prime Minister as follows:

“I last saw him propped up in bed, dictating correspondence to his secretary. He had a bird standing on his head, which flew down and began drinking his glass of whisky and soda”. Bizarre, to say the least.

France, Israel and Britain in secret agreement

Marr described Eden as ‘popular’ and during the 1955 general election he travelled by train and at each station was greeted by women with flowers. Whether this was fundamental to the re-election of the Tories in that year is doubtful, but his premiership proved to be short-lived. The biggest crisis in this period was over the invasion of Egypt, after the nationalist leader, Colonel Nasser, had the temerity to nationalise the Suez Canal.

The canal was part owned by Britain and France and 25% of all imports, including 67% of oil supplies, passed through it. A secret agreement was reached between Britain, France and Israel, which involved an Israeli attack on Egypt followed by an invasion of British and French forces as alleged “peace-makers”. This was no more than a pretext to re-take the retaking of the canal. Britain had failed to consult the US in any of all this and the US (and USSR) demanded British and French withdrawn, which is what happened. It was an ignominious humiliation and an unmitigated disaster for British capitalism, showing for all the world to see that Britain was reduced to a second or third-rate military and diplomatic power. As Marr said in the programme, the Suez affair was a military success, but a political disaster.

Reservists refusing the call-up

There were also repercussions on the home front. Labour were critical of Eden’s actions and there were even many reservists who refused to report for duty over the invasion. Some wrote B*****ks on their call-up papers, according to Marr. Despite a campaign of vilification in the western press against Nasser, which included the claim that he was a ‘Arab Nazi’, around half of British people, according to polls, opposed the action, which caused a shortage of oil shortages and cash. Eisenhower, the US President at the time, refused to give any assistance until Britain withdrew its troops.

Eden, who lied to Parliament about the secret agreement with Israel, went on holiday to Jamaica and when he returned, a cabal of senior Tories asked for his resignation. That was how it was done in those days – no voting among Tory MPs, just a group of ‘men in grey suites’ deciding that he had to go. He was replaced by Harold Macmillan. According to Marr, Macmillan was one of only a handful of Cabinet members who knew of Eden’s conspiracy. Even Lord Mountbatten, former Viceroy of India and an adviser to the Queen, described many of Tory ministers as “lunatics”. The Suez Crisis had revealed Britain’s much diminished role in the world, leaving at that time only the USA and USSR as major world powers.

Aristocratic leadership of Tories

It is interesting that Marr comments on the narrow circle of upper-class Tories who ruled Britain at that time. They all had aristocratic and public-school backgrounds as essential requirements for high political power. Macmillan was personally related to 35 of the 85 ministers in parliament. There were seven in the cabinet and only two hadn’t gone to ‘public’ (ie private) schools. This extended even beyond Parliament. Marr devoted a part of his programme to the West End Theatre which was run by Hugh “Binky” Beaumont, another toff, who became one of the most successful and influential manager-producers in the West End in this period. The West End catered for respectable middle-class and middle-aged people, but by the late 50s, some of the deference and snobbishness began to be undermined by a growing challenge from comedians and satirists.

Hundreds of black youth fought racists and police

Marr described the events of 1958 in Notting Hill, in West London, as Britain’s first ‘race riot’. It began as a minor incident, allegedly an argument between a couple, and it ended in four nights of rioting. Large gangs of whites entered the area with the intention of attacking black people. Marr observed that there was little reaction from the police, but the white racists and police got more than they bargained for as around 300 blacks fought them and the police.

The 50s and early 60s were rife with open racism; the idea of racial superiority was built into the whole justification for the British Empire and colonialism. It was common for notices in the windows of some boarding houses to read, “no coloureds, no Irish and no dogs” and the lack of housing fuelled these prejudices.

‘Empire’ rebranded as Commonwealth

The humiliation of Britain in the Suez crises and the struggle for political independence among former British colonies resulted in the former empire having to be re-branded as the Commonwealth. It also drove Macmillan to seek membership of the European Common Market, as it then was, the forerunner of the EU. However, negotiations failed, with the French leader, Charles De Gaulle putting a French veto on a deal. According to Marr, the talks failed because the French demanded an end to links with Commonwealth countries like Australia and Canada.

Then, as now, for Britain to have a so-called ‘independent’ nuclear capability was seen by the Tories and Labour’s right-wing as the only way of posturing as a ‘world’ power. There were early attempts by Britain to develop its own rocket technology – ‘Blue Streak’ was the British-designed rocket – but it proved far too expensive for a relatively small economy like Britain’s, so in 1961 a deal was struck with the US to supply nuclear missiles that could be launched from submarines. They are still based today in a loch near Glasgow, the third largest city in the UK, and when Macmillan questioned the advisability of having missiles near a city, Eisenhower promptly dismissed him.

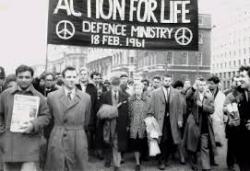

From that time to this, the so-called ‘British’ nuclear deterrent has never been independent, but no more than an appendage to the US arsenal, fully under the command and control of the Pentagon. What those controversies did lead to, however, were large demonstrations against nuclear weapons and the rise of CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, with its iconic logo, supported by probably a significant number of rank and file Labour members. According to Marr, around 33% of people in the UK opposed the deployment of nuclear weapons in Britain.

Profumo – the big scandal of early 1960s

Finally, Marr described how the British establishment were good (and still are) at covering up scandals. There were scandals involving the royals, politicians and many other dignitaries. One of the best known, the Profumo scandal, involved the then ‘Minister for War’ (equivalent to Defence Minister today) having an affair with prostitutes who were also patronised by Russian diplomats. Not only did John Profumo resign, but the Prime Minister, Harold McMillan, went as well, and almost certainly this sealed the Tories’ fate in the next general election in 1964.

McMillan was replaced by Lord Home – again through a secretive cabal of men in suits – who as a peer had to relinquish his title and seat in the Lords, before becoming Prime Minister. Alec-Douglas Home, as he became, was cut from pretty much the same aristocratic cloth as previous Tory leaders: landed gentry, speaking with a plum in his mouth and from another planet as far as ordinary people were concerned. Home was to lose the next election to a pipe-smoking Labour leader with a northern accent and more than a nodding acquaintance with the twentieth century.

Shop stewards’ movement

Marr began this programme by stating that even in the 1950s Britain was still the world’s second richest nation. He also mentioned the power of the trade unions in those days and in particular, the growth of the shop stewards’ movement across all areas of industry. There was more or less full employment and that was a huge factor in strengthening the position of organised labour. One down-side of this programme is Marr’s apparent interest in matters that seem secondary in nature and the lack of emphasis on more important issues.

The 50s were the beginnings of the long post-war boom that was to last for 25 years. For the majority in the industrialized world, living standards improved more or less uninterruptedly for that whole period, in sharp contrast to the interwar years. Macmillan even fought the 1959 general election with the slogan, “you’ve never had it so good” and he wasn’t far wrong. He won that election for the Tories. Strangely, that wasn’t even mentioned by Andrew Marr.

New Labour under a different name

Marr also failed to mention the term “Butskellism”, which in reality was a forerunner of New Labour. The main architect of Tory economic policy was ‘Rab’ Butler, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Labour’s leader, Hugh Gaitskell, was considered to be so close to the Tories in his general outlook that the two names were put together as Butskellism. This was also reflected in Gaitskell’s attempt to remove Labour’s socialist heritage, its famous Clause 4, part 4 of the constitution. Labour leaders who follow these ideas are what we would call today ‘Tory-lite’.

The similarity in their policies was the fundamental reason for 13 years of Conservative rule from 1951 to 1964. Why vote for Tory-lite, when you could vote for the real Tory? Although Britain enjoyed improved living standards, Britain was falling behind its rivals. There was also a growing opposition among young people particularly to the mores and supposed ‘standards’ of the day. The programmes dealing with the next period will reveal this.

May 21, 2020