By Abigail Pollock, key worker and single mother

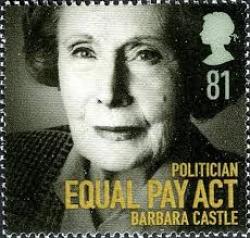

On Friday a press release from Helen Pearce of Labour Unions harnessed the moment, stating “on this day 50 years ago a Labour Government passed the Equal Pay Act outlawing workplace pay discrimination”. Times have been tough recently and if anyone ever gets off furlough it is nice of the Party to remind women that they get paid the same as men.

Women’s pay still lags behind that of men

Unfortunately, those women members still reading the Guardian post-Corbyn would have noted in a simultaneous article that women’s pay was 37% behind men in 1973 and is now 17% behind, and please – don’t ask a BAME woman about her pay, or lack of it. The optimism falls even flatter when women across Britain realise, they were so busy applying to the Trace and Track temporary jobs with the NHS, advertised last week on Mumsnet, they forget to load the dishwasher.

However, it is worth remembering that The Equal Pay Act was a revolutionary piece of legislation, that along with the Pill and mini-skirts, transformed women’s lives forever. In the public mind the victory has become forever associated with Red Babs, Essex Girls and the biggest council estate in Europe, formally called the Becontree but known to everyone else as Dagenham.

The dispute with Ford Motors had been rumbling since 1965, at least, and was a reflection of wider social change. The global corporation opted for Dagenham, way back in the 1930s, citing its unparalleled access to the River Roding the Thames and, according to the film; actually filmed in derelict Basildon just before they “regenerated”; cheap mini-skirted Labour.

Dagenham was a hotbed of radicalism

Nevertheless, By the late 1960s, Dagenham was a hotbed of radicalism and female workers were at the forefront of Trade Unionism. Lead by a coterie of older women with mouths to feed and younger women working for pin money, they ousted a stale, male patriarchy of bored shop- stewards to reinvigorate the floor in the car upholstery section of Ford’s biggest car plant in Europe. All of this clearly demonstrating that Dagenham is really a little place with a big name, just like Sally Hawkins is a little actress with a big love for Paddington, and Dagenham, and Bob Hoskins is a loveable little shop steward.

The smash hit film, Made in Dagenham (MID) put the original heroes of socialist feminism back on the map, but for those of us on the female left, the work of these women has long been known. Judith Garfield, founder of Eastside Heritage, and the Labour candidate for the GLA seat of Havering and Redbridge in the upcoming elections for a London Mayor and Assembly, was the one of the first to research the story. “In the 90s”, she told me, “I had the privilege of interviewing many of the Fords Dagenham machinists, many of whom participated in the 1968 strike. I was surprised that many of them said to me “Why do you want to know? We did nothing special, except fight for our fair share to feed our kids and support our families”.

Hard-fought strike for equal pay

“Like many women” Judith added, “their story was forgotten. However, they felt that the Equal Pay Act campaigners had failed to recognise how hard-fought their strike for equal pay was. They made huge sacrifices as working class women for this legislation to reach the statue books. They had all made a huge difference. They were all skilled workers treated as unskilled and were fighting for in their words ‘What was right and fair’”.

Clearly, there was a huge fear of the skilled and educated woman as Judith notes in an anecdote about favouring the young and inexperienced over the hard-bitten, more mature lady

“One of the women interviewed told me a story that I have never forgotten and am pleased to say has now been used extensively, documenting how skilled and talented these women were:

“One of the ladies who worked with me had been a machinist for [Norman] Hartnell,” she said. “She’d been a dressmaker making the Queen’s clothes. She went for a test at Ford and they turned her down. Now if you’re working for Hartnell you must be a good machinist mustn’t you? [Her brother] had been at Fords quite a few years then. He said: ‘Why have you turned my sister down? She’s been making the Queen’s clothes and you’re telling me she can’t machine?’ So they had her back and gave her a job”.

Fake garment factory on BBC

On Saturday the BBC have got in on the act by commissioning a three-parter called Back in Time to the Factory. In it, Alex Jones from the One Show, took an attractive cast of Welsh dolls and installed them in a fake garment factory, presumably re-enacting Dagenham in the Rhondda. In next week’s episode they will all go on strike, showing that you can’t beat a bit of nostalgia to show you how lucky you are, not to have a job in the 21st Century, even if you’re not actually paid or are an intern.

The yearn to celebrate 50 years since the Equal Pay Act is a bit like the mania for the suffragettes in 2018. It is a keystone of democracy to celebrate certainties: the vote, paid labour, white-goods – without interrogating the basic economics of the state. The movement for waged work for women was a long-time brewing. The film tried to crystallise it into one 90-minute cinematic strike, but the real battle was harder fought and distinctly linked to the two Great Wars.

The impact of the WWI on women and suffrage is well known, but the pushback against women in the workplace after WWII was at its hardest in 1950s UK and US industry.

An in-built aversion to wage appreciation

The late Twentieth Century housewife was a consumerist creation but at the core of the post-war boom was an economic conundrum. 1960s affluence was based on white goods and domestic luxury, the income of working-class families had to be raised but capital has an inbuilt aversion to wage appreciation, particularly towards the lumpen proletariat and its wife.

Long after the EPA, Jayaben Desai would fight at Grunwick, females in the NUT would still grapple with the marriage bar in their long-running 80s dispute, but capitalism would declare the battle won.

For some liberal feminists it is, but for radical feminist the issue still rankles.

According to the Guardian (May 25) “Since the 2007-08 financial year, employment tribunals in England and Wales have received more than 368,000 complaints relating to equal pay, an average of almost 29,000 complaints a year.” Recently I sat with a hard-bitten trade unionist at the musical of MID; he was entranced by the motley crew of Pans People cast-offs gyrating and protesting. In the end, he concluded, “you’d think all unions are bad, all men are bad”.

The notion that value is linked to pay rate is as stubborn a credo of the working -class as it is to the old-fashioned convener. But what the EPA shows is that women might be far better trade unionists than men, by virtue of their lower status. Every day, I thank my lucky stars for the Bill, the Pill and my washing machine.

June 3, 2020