By Andy Fenwick, Worcester Labour Party

Discussion on what Socialist Art would be is often confused with an elitist overview pushing an ideal that only the Artist knows what Art is. We see it today in the offerings that are presented for the Turner Prize.

However, in the USSR just after the revolution, a hundred artist manifestos were published, all denouncing ‘bourgeoisie’ art and proposing a new form of art and culture. An exponent of this new art was Dziga Vertov, a Russian film maker, who created a movie for the cinema called Man with a Movie Camera, which was a simple concept to show life in the USSR, warts and all. It was a documentary, without any dialogue, just showing ordinary soviet citizens going about their business. We are all aware of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, but unlike a scripted drama, Man with a Movie Camera needed no artificial theatrical tools to carry it.

When it was released, Vertov’s film was a sensation, not only in Russia but internationally, but was the art form or the political/social context of the time diluting the strength of the documentary to tell truth to power? The examination of truth and reality has to go beyond the style of the film making or the political constraints. However, it is not possible to ignore these issues out of hand as the influence can be seen in the movie itself. This work needs to put into context: Vertov was making films in a time and place very different from ours.

Artists abandoned easel painting

For any analysis of Man with a Movie Camera it is necessary to understand the mood and perspectives of the art intelligentsia in post-revolutionary Russia. Just after the October revolution, soviet artists and designers attempted to put their talents to the use of the new communist state. Most of them abandoned formal easel painting because even in its most radical forms, like cubism and futurism, it was seen as overtly ‘bourgeois’. They turned instead to geometric design. The slogan for these “constructivists” was “Art into Life” and their goal was, as Vladimir Tatlin, the most influential of these avant-garde artists put it, “to unite purely artistic forms with utilitarian intentions.”

In their most extreme formulations, the constructivists announced “Art is finished! It has no place in the human labour apparatus. Labour, technology, organization…that is the ideology of our time.” These ideas were fully expressed in a “realistic manifesto”, published in August 1920, and written by sculptor, Naum Gabo. “The artist constructs a new symbol with his brush. This symbol is not a recognizable form of anything which is already finished, already made, already existing in the world – it is a symbol of a new world, which is being built upon and which exists by way of people.”.

The constructivists found an echo in Vertov’s film. “The film drama is the Opium of the people…down with Bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios…long live life as it is!” It is this phase that has had an echo down the years and is still reflected in social realism cinema today.

Artistic ideals endorsed by Lenin

The freedom to pursue these artistic ideals was endorsed by Lenin, who in his vast array writings only committed 264 words to cinema, and suggested only two conditions, first that film should be without obscenity or counter-revolutionary and, second, that it should represent the life of peoples of all countries. In a reminiscence reported nine years after his death, a phrase linked to the Lenin was, “You must remember always that of all the arts the most important for us is the cinema”. However, this can be challenged, as the article also refers to Lenin proposing “Soviet realities” in cinema: this was part of the later falsification of Lenin’s ideas by Stalin, to prop up the Stalinist idea of ‘socialism in one country’ and it produced the sterile “soviet realism” school of Stalinist art.

Vertov was shooting his documentary at a most decisive time in the USSR; Stalin was consolidating his authority and in 1927 he was powerful enough to expel Trotsky and the Left Opposition, followed a year later with the first of the Stalinist show trials. Yet the full weight of reaction was not yet perceived by workers and Vertov was able to film ordinary Soviet life, albeit safely away from Moscow and mainly in the Ukraine. The argument has been put forward that “it may not obviously be marching to Stalin’s orders; but at its heart, a lesson in conformity it most definitely remains”, but this is not backed up by the evidence that Vertov’s art suffered much from the needs of ‘soviet realism’ and scripts needing approval. Even Eisenstein eventually compromised his own artistic integrity, through subservience to the party line, while Vertov courageously declined to do so.

Camera being filmed while filming others

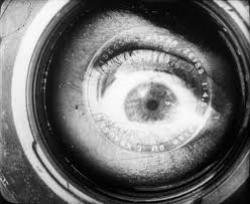

In the opening scenes of Man With a Movie Camera, we see the camera as an eye, recording not just simple images but highly complex images-within-an-image. A constant theme running through is the idea of the artist as the worker and the worker as the artist, with the cameraman being filmed whilst filming others. The film editor has skilfully spliced film into a cut-away to millworkers spinning yarn and replicating each other’s skills.

Vertov enforces his 1922 manifesto We, “We make peace between man and machine”, by use of a ceaseless motif of happy workers at their work-stations. He was praised by artists like Charlie Chaplin, a view according Jean-Pierre Dardenne in a TV documentary “Chaplin Today: Modern Times(2003)”, that Chaplin expanded upon as he viewed mechanical labour as liberating whilst in the hands of the workers, but a tool of imprisonment when Fords controlled the speed of the line. It is from Vertov’s work that Chaplin took inspiration for the factory scene in Modern Times.

Man With The Movie Camera links an empty city and an empty cinema, with its empty seats as audiences rushes in to fill its seats; we are presented with the awaking city to serve as a form of commentary that in a soviet city you are not only the observer, but also the subject of the film, within a “life caught unawares” scenario. The invasion of privacy permitted by Vertov would be doubtful today; the relationship between subject and filmmaker, as with Jack Kennedy in Primary or Bob Dylan in Don’t Look Back, gives control of access back to the subject

Glossing over harsh truths

Although Vertov came out of the Agit-Prop tradition of the post-revolutionary civil war and there was a need to gloss over harsh truths for the sake of the revolution, in the opening scenes we do not see the soviet nirvana. Instead, we see homeless sleeping rough on the streets. The reality of life has its parallels from the individual to the city, with people waking up to the awakening of the city’s transport, the washing of the young woman, the washing of the streets, the blinking of eyes and the blinking of window blinds; the greatest parallel is the eye reflected in the camera lens. The continuous use of unrelated montage to confront the existence of reality in image is present and then gone. In his book Constructivism in Film: The Man with the Movie Camera Vlada Petric suggested that Vertov was seeing his art in a dialectical, Marxist way, in that an object comes into existence and is then is no longer seen, such as in the birth and funeral sequences of the film.

Vertov is honest in the presentation of the camera’s images. As Seth Feldman illustrates in ‘Peace between Man and Machine’: Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera.” , there is a depiction of a rich soviet middle class that still existed and it is captured by the shooting of a well-dressed woman in an open top car, calling on her maid to carry a large trunk. If Vertov was to propagandise his film in response to the new Marxists state, this scene would not have made it past the edit. Again, the juxtaposing of the beer hall and its rowdy participants were a contrast to the intellectual activities at the workers’ centre.

Interview with Vertov’s brother

For some, the biggest challenge to the truth is whose movie it was. In reproducing an interview with Vertov’s brother, Mikhail Kaufman, doubt is placed in the mind of the reader. The suggestion is that the innovations and novel camera work allowed Vertov’s “capturing life unawares” theory is put into practice. In Vlada Petric “Constructivism in Film: The Man with a Movie Camera” Mikhail Kaufman describes the childhood of the two brothers, where he was interested in the visual image and Vertov was more poetically minded. In reality, this movie was more of a collaborative effort rather than the vison of a single individual.

The major question for this film is this: is it documentary, propaganda or avant-garde art? To answer this, specific criteria are needed to evaluate the movie. For the documentary the movie has to be true representation of its subjects and adhere to a communal sense of reality. Vertov is able to present a version of truth and reality with the minimal adjustments, such as the intrusion into the young woman’s bedroom.

As a propaganda film, has it shown its subjects in a positive light? In the context of the Depression of the 1930s, we would need to ask, “Would I like to live in this world presented by film?” For a time in the 1930s, a sizeable number of people outside the USSR were attracted to it, because of the mass unemployment in the capitalist countries and apparent full employment in the USSR. This helped to lead to a rapid growth in communist parties around the world. A black American activist, Harry Haywood, moved to Moscow and lived most of the 1930s in Russia where he wrote his autobiography Black Bolshevik.

How do we define avante-garde?

Before we consider if the film can be avant-garde we need to define avant-garde. The avant-garde are those people or works that are experimental, radical or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society. It is frequently characterized by aesthetic innovation and initial unacceptability. Are the techniques and visual composition more radical in form than in previous art works? The editing of Vertov’s film allows the development of a soviet montage and self-referencing back to the theme but technique is not unusual. Man with a Movie Camera give us the appearance of avant-garde but the key factor is the self-declaration in Vertov’s “We” manifesto; avant-garde art as a self-built tautology ‘we are avant-garde therefore our art is avant-garde’.

The movie is available on YouTube here and is just over an hour long. As well as a representation of soviet life, it could be a good basis for a discussion on “What is Art?” and where it links to socialist ideas.

June 25, 2020