By Mark Langabeer, Newton Abbot Labour member.

Modern day Iraq is practically a ‘failed state’, incapable of providing basic services for the majority of its population and it is still suffering from the death and devastation of the brutal invasion by the USA and Britain.

A new BB2 documentary series, Once Upon a Time in Iraq, gives some good background the war and describes its effects, using personal accounts given by civilians, journalists and soldiers of the War.

The first programme begins with footage of Bush, USA President of the time, declaring war on those states that he alleged were ‘harbouring terrorism’. The horrific attack on the Twin Towers in New York was the pretext for wars against nations described by Bush as the Axis of Evil.

Tony Blair’s lies and the ‘dirty dossier’

Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was firmly in Bush’s sights, even though his regime was opposed to Al-Qaeda, the supposed originator of the Twin Towers attack. Tony Blair, UK Prime Minister, had already agreed to support the US invasion and the lies he told about “weapons of mass destruction”, in what later became known as the “dirty dossier”, were merely the pretext. The stated aim of removing Saddam was the restoration of “freedom and democracy”, although the end result was anything but.

The programme reminded viewers that by the time of the invasion Iraq had already been subject to thirteen years of sanctions and a no-fly zone by US forces. Many Iraqis could be forgiven for believing that a state of war already existed and that the invasion in March 2003 was just its final act. Within a month, Saddam’s forces were defeated, and he was forced into hiding.

Although Bush was quick to declare “victory”, the invasion was only the beginning of the problems. There had been little or no planning for the aftermath of Saddam’s regime and the vacuum left behind saw an orgy of looting, lawlessness and chaos. Anything that wasn’t nailed down was ransacked, including museum artifacts thousands of years old.

Iraq was awash with arms. There was even a picture of doctors with guns trying to prevent the looting of drugs and medicinal equipment. It was noted by one contributor, that US troops occupying Iraq were protecting the Ministry of Oil and its instillations, but little else. Dexter Filkins, of the New York Times, believed that the looting of state assets was the beginning of a downward spiral in the relations between the Americans and Iraqis.

There were no police, electricity or water. Donald Rumsfeld, the US Defence Secretary, described this as an example of new-found freedoms, even if it meant freedom to make bad choices.

The Insurgency begins

Following the invasion, there were around 150,000 US troops in Iraq, tasked with “security”. and Paul Bremer was appointed as head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, given the job of reconstruction, but little was done in reality. Iraq was a huge open cess-pit of corruption. There were stories at the time of US cargo planes importing – literally – palette loads of dollar bills, amounting to billions, to pay off officials, warlords and business and political leaders. This was money that disappeared into a black hole of corruption.

Filkins believed that the decision to ban all members of the Baathist Party, the which had been led by Saddam, from their posts and the decision to completely disband the Iraqi armed forces, provided ideal conditions for the insurgency that developed subsequently.

Many Iraqis had welcomed the fall of Saddam, particularly those from the Shia community, the majority sect in Iraq, and the Kurdish population, because of the past history of repression against these groups. But that was not true among Sunnis, who had been favoured by Saddam and who were therefore the epicentre of the first uprising against the USA. As one contributor to the programme said, “we were all Baathists”. The first attacks on US forces spread to the major cities, including the capital, Baghdad.

Enter Lt Colonel Nathan Sassaman, who was head of a battalion of US troops. He was regarded as someone destined to reach the rank of general, and he began his time in Iraq with the idea of ‘winning hearts and minds’. But following the death of a colleague, it turned into its opposite. One contributor described Sassaman’s forces as “savage” and that they were more like “occupiers” than “liberators”. Sassaman was reprimanded following an assault by troops under his command, later leaving the army and going right over to an anti-war point of view.

The Fallujah uprising

Fallujah, a majority Sunni city, was the centre of the insurgency and only 40 miles away from Baghdad and here four US soldiers’ bodies were strung up on a bridge over the Euphrates. By this stage, the home-grown insurgency was joined by Al-Qaeda – ironically previously suppressed in Iraq – and one of its leaders, Al Zarqawi, an extreme Sunni nationalist.

So only a year after Bush’s declaration of “victory”, an order was given for 8,000 US marines to attack Fallujah and kill all of those who resisted. Many of the population had already fled the city, but 50,000 civilians remained, mostly because they were too poor to move and in the subsequent fighting at least 600 civilians were killed.

An Iraqi mother told the programme makers that chemical bombs were used by the US forces and that the Americans even detained doctors. The New York Times correspondent, Filkins, made the point that the rules of engagement had changed from firing “only when fired upon” to firing at anyone who was a “suspected terrorist”. Winning hearts and minds was over.

The capture of Saddam

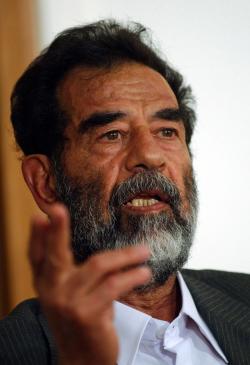

After the initial invasion, Saddam had escaped capture and there was a belief in the British/US camps that his capture would end the insurgency and a bounty of $25 million was offered to anyone who gave information on his whereabouts. Saddam (pictured above) was eventually found on a farm in a small underground bunker.

John Nixon, described as the CIA analyst who interrogated Saddam about the weapons of mass destruction, described a man who had “a certain aura” about him. One of his guards even said that Saddam had told him that he could restore order in Iraq in an hour, “forty-five minutes to get changed and have a shave, and fifteen minutes to announce his return as leader”. That could well have been true.

The trial of Saddam and his televised execution by hanging was cheered by many Iraqis, but one contributor in the documentary believed that the word on the street was that Saddam was seen as a “martyr” and rather than the insurgency declining, it actually intensified after the execution. In fact, CIA agent Nixon thought that the public hanging was a big turning point, including in his own outlook on the conflict.

Civil war and the rise of ISIS

With the insurgency under the command of Sunni fundamentalist Al Zarqawi, it took on a sectarian colouration, with attacks on Shia religious gatherings. These were clearly intended to provoke retaliation and sectarian conflict. Many civilians fled from Baghdad and around two million left the country altogether, but it was the least well off who were forced to remain as the civil war intensified after elections in 2005.

These elections were held under an artificially-imposed constitution that reinforced sectarianism, with the President, Prime Minister and parliamentary Speaker all being designated from particular sectarian groups. The fixed proportions of patronage extended right through all government ministries and all the way down to the streets. Thus, the imposed US/UK constitutional arrangement, instead of establishing “freedom and democracy” more or less guaranteed sectarian conflict and chaos.

Sure enough, the election of Prime Minister Maliki, a Shia, intensified the divide and as the conflict intensified, US forces stood aside, unless they were under attack themselves. By 2011, US forces had begun to withdraw, leaving only enough troops to man airbases and train Iraqi troops.

ISIS stopped by Shia and Kurdish militias

By 2014, with the revolt against the Assad regime in Syria to the north gaining ground, the twin Sunni insurgencies in the two neighbouring countries merged in the form of The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), a movement that quickly gained a huge area under its control.

Mosul, the third largest city in Iraq, was taken with little resistance from Iraqi forces which disintegrated, leaving their weaponry for the ISIS forces to pick up. Most joined the Iraqi troops had only joined up to get a wage in the first place, there being little else in a devastated country to provide a livelihood. The Islamic State advanced as far as Tikrit, the birthplace of Saddam and not far north of Baghdad. Here, the Iraqi officers fled, leaving army cadets to be massacred by ISIS forces.

ISIS gained some support among the Sunni population at first, by pointing to the sectarian advantages allegedly given to Shia Muslims and to the corruption of the whole Baghdad regime. But they were bitterly opposed by Shia Muslims and it was due to Shia militias, recruited in large numbers at relatively short notice, that the ISIS advance was stopped and reversed. It has been the Shia-based forces, with a significant contribution by Kurdish militias, that have driven ISIS out of Iraq in the following years.

Before the conflict, Iraq was no democracy. Saddam Hussein ruled with an iron fist, prepared to use all the military means at his disposal, including poison gas, against his own people. But the real aims of the USA and UK in Iraq were not “democracy” – after all, they had armed Saddam in his long war with Iran – but oil and strategic influence. In the event, they turned what had been regarded as one of the more cosmopolitan states in the Middle East, into a sea of rubble and a nest of corrupt sectarianism.

2019 uprisings in Baghdad.

What about the future of Iraq? One contributor in the programme said that he had left Iraq but had then decided to return because he missed his mum and his brothers and sisters. He even tried to organize a ‘reunite party’ with old high school friends, but one of them refused to go because a Sunni had been invited. Clearly, as was said, “the old Iraq has gone”, and you are now “either Shia or Sunni”.

However, it has to be said that in 2019, when there were mass demonstrations against corruption, social conditions and low wages – demonstrations in which over four hundred were killed by security forces – the participants were Shia and Sunni together.

The rottenness and corruption all across the state is bleeding the life out of the population. Even in the last month, with temperatures in Baghdad reaching as high as 50oC, there were power cuts, meaning that air conditioning and electric cooling equipment couldn’t be used – despite Iraq being awash oil. All the conditions exist today for a revival of struggle and resistance and that, at least gives some hope for the future.

The BBC series of five episodes is available on i-player and is well worth watching.

August 13, 2020