By Ray Goodspeed, chair Leyton and Wanstead CLP, personal capacity

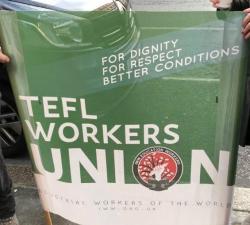

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW – the old ‘Wobblies’) is taking the lead in organizing TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) workers – teachers, as well as admin, reception and marketing staff – who have no tradition at all of trade union organization.

Precarious or temporary work is increasingly used in colleges and universities, but it is being resisted by the University and College Union (UCU). However, private language schools are the dark underworld of the education sector and it is here that most TEFL teaching goes on. However, the seeds of union organization are starting slowly to germinate among TEFL workers.

Accredited IWW representative

Although recently retired, I am an accredited representative of the IWW and can work on individual cases or collective disputes. Being retired is useful in an industry where victimisation of trade union members is routine.

The TEFL industry in the UK is split into two main layers. The upper layer is made up of language school chains, owned by relatively reputable companies or individual schools run by more responsible owners. However, beneath that are semi-criminal (or actually criminal), fly-by-night operations that flout any accepted standard of behaviour. Covid-19 has been a disaster for the whole TEFL sector, which is really a kind of specialised tourism. Many schools have closed, and workers have been treated appallingly in the process.

Even the better schools routinely employ teachers on zero-hour contracts, with low pay and inadequate or non-existent payment for preparation, meetings, marking or training sessions. My first employer in the UK granted only twelve days holiday a year, plus bank holidays, but three of the twelve days had to be over Christmas, when the school closed! The same school paid no sick pay and statutory sick pay only after the first few days. I once taught English language with no voice for a week – that’s 30 classroom hours – because I couldn’t afford to be ill. It did lead to some creative teaching methods, though! Language schools do not have the usual academic holidays, of course, and Summer is the busiest season. Only a change in the law improved it.

In the better schools, zero-hours employees get employment rights after two years and a relatively regular set of hours. But some schools find a way around that by making employees sign a series of temporary contracts. After a year and 50 weeks or so, the work mysteriously dries up, often over Christmas, and the teacher is “let go” on the clear mutual understanding that they will be suddenly needed again two or three weeks later and re-hired from scratch. One well-known chain school has been doing this for nine years! When it recently made most of its staff redundant owing to the Covid-19 crisis, all but a couple of staff received NO redundancy payments, in spite of working there for between two and eight years. Instead, the company offered three weeks additional notice pay as a ‘gesture of goodwill’, for which staff were expected to be grateful.

Another ‘reputable’ school chain went into liquidation on July 31 (the day they would be expected to contribute to the furlough payments), forcing all of its teachers and administrators into redundancy. A week later, the owners opened another school under the same name in a different city.

Prides itself on its ‘fun’ image

The whole TEFL industry likes to pride itself on its informal and ‘fun’ image. That is how it is marketed to the usually well-off foreign students who come to the UK to improve their language skills or to prepare for university-entrance English exams.

TEFL work abroad has the image of ‘something to do in your gap year’ and not serious work. In fact, most teachers I worked with were in their 30s and 40s and often older, and many had worked in the industry, either abroad or in the UK for several years.

They are nearly all graduates, with extra teaching certificates, and often have additional masters’ level diplomas or degrees. Yet the salary is often a few thousand pounds a year below the national median income and miles below the median income in London or the other expensive tourist towns and cities where the industry is concentrated. Owning a house or even renting can be almost impossible without substantial alternative sources of income, and starting a family means either living in poverty or getting out of the industry altogether.

Unpaid extra work

This ‘fun’ image leads to demands for ‘extra’ work, providing unpaid extra help to students or being expected to socialise to enhance the ‘student experience’, both often freely given by teachers who want to do their best for their students. It also brings a casual approach to disciplinary procedures. A quick chat with the boss can suddenly turn into a verbal warning with no formal notice or other disciplinary procedures. I know two teachers who were given a verbal warning ‘off the cuff’ for rolling their eyes and shrugging their shoulders in an internal team meeting! Both were non-white. A school that supplies online teaching from the UK to China fined a teacher because the students said they did not smile enough. The same school fined teachers $80 for being late to class. Bullying and harassment are rife.

A particular problem is ‘native-speakerism’, i.e. when some students and schools have the (completely wrong) assumption that native English speakers are always better teachers. Non-native teachers are thus concentrated in lower prestige schools on less money and with worse conditions. This attitude also leads to discrimination against BAME staff, even native speakers, who don’t match the stereotypical assumption of what an English person looks like.

Administration and support staff poorly treated

Administration staff such as student services, reception or marketing are treated just as badly as teachers. Sometimes they have guaranteed hours, but they are still badly paid and often badly treated. Many are ex-students who start as unpaid interns, or on expenses only. Some of these stay longer, using their vital language skills. The IWW/ TEFL workers union includes all workers in a school into one union as an organising principle.

In the lower layers of the industry the situation is, unbelievably, much worse. This is the domain of fake self-employment, with absurd contracts, where staff have to ‘invoice’ the bosses every month and then wait two weeks to be paid. This means no holidays at all, no sick pay, no pension and no employment rights. Contracts are simply terminated, and no more work offered if your face does not fit. Wages are more often than not paid late or even not at all.

Failed to pay for work already done

One school that closed in March, as a result of Covid, failed to pay thousands of pounds for work already carried out in the previous six weeks or more. An Employment Tribunal to hear this case has just taken place, which hinged on the issue of fake self-employment – brought on behalf of fifteen staff by the IWW. And we won! But even this win does not guarantee that staff will get their money, as companies of this kind simply disappear or declare bankruptcy. It is not at all unheard of for staff to turn up on a Monday morning to find the building empty and locked and owners disappeared, along with all owed wages

Organising carefully and secretly

In such a sector, it is no surprise that trade union organisation has to be very careful and even secretive. When the union leaflets schools, staff are often too scared to take one in public or to talk to the leafletters, so all contacts have to be very discreet. The first secret meetings can be in a park or café (not a pub, though!) and then, through quiet conversations in corners, or through secret WhatsApp groups, the number of members grows, until the union has enough members and they have enough confidence to declare themselves. It is good to see the surprise and annoyance on the bosses’ faces when a worker has the nerve to ask for proper written notice of a disciplinary and then turns up with a union rep.

In this business, getting employers to actually grant the legal minimum or follow ACAS guidance is a huge victory in itself. Failure to abide by procedures, or by the terms of contracts has allowed the union to stop disciplinary measures or to talk down the ‘punishment’. Written warnings become verbal warnings etc. Slightly enhanced redundancy payments have been negotiated.

Tactics, like all the staff wearing the same colour on a day, to play mind games on the managers, have been used. A ‘work-in’ to prepare lessons in the staffroom (on a Monday morning with dozens of new students arriving!) was also effective in getting concessions, like payment for training and team meetings, payment for sickness, and some minimal paid preparation time, etc.

Blitzing a school’s social media outlets

Getting other, non-TEFL, members of the union to picket schools and leaflet students in a range of their native languages has serious embarrassment value, as does blitzing a school’s social media outlets and leaving poor reviews. But the threat of victimisation of union members or even closing a school altogether is a powerful weapon in the hands of the language school owners. One school sacked made all its teachers ‘redundant’ and then replaced them with agency staff, so we picketed the agency and protested outside a different school where they had hired classrooms. This bad publicity forced them to offer a better redundancy package. We also explained the situation to the young students going in for lessons and encouraged them to ask what happened to their teacher! I am learning trade union vocabulary in several languages!

While the IWW takes on individual cases or group claims right up to an Employment Tribunal, or to court if necessary, we always stress collective action to try to win concessions. Individual grievances are generalised to include other fellow workers wherever possible. Sometimes we get victories, but there is no escaping the need to massively increase recruitment among many more schools.

A union led by its members

IWW has virtually no full-time staff, just a network or lay reps like me who take on cases in any sector as they arise – TEFL one week, brewery workers the next. We are led by our members, not by any top-heavy bureaucracy. I have been in other unions, on principle, but got nothing from them for my work, just loads of adverts for cheap holidays and insurance. The GMB failed for three years to put me in the right branch. The IWW stood outside my school handing out leaflets for an (excellent) training session on the legal rights of zero-hours workers. I went along, and here I am.

Precarious workers in a many different fields have started organising to protect their rights. While some large, long-established trade unions have played a significant role in some struggles, other, less well-known and very small, unions have often been key. The Independent Workers Union of Great Britain (IWGB) has recently helped University of London cleaners to be transferred to in-house contracts, following on from security and other staff in earlier disputes.

Their ‘tres cosas’ (three things) campaign for cleaners in the University of London, employed by Balfour Beattie, began the successful fight from 2011 for increased annual leave, sick pay and adequate pension contributions. The IWGB has also organised Deliveroo couriers, Uber drivers and foster carers. Another union, United Voices of the World (UVW) organised cleaners, security guards and receptionists at the Ministry of Justice, and organised cleaners, porters and caterers at five London hospitals, leading a strike and getting the services taken back in-house on full-rights from April 2020. These and many other campaigns, often focus on migrant workers and are characterised by vibrant, fun and unconventional protests and picketing.

Structural changes in labour market

A wider discussion needs to be had about these unions in the labour movement. The classical position of Marxists has generally been not to support splits in trade unions. Yet the IWGB was a breakaway from Unison and Unite, by workers tired of the lack of enthusiasm for taking up their particular issues. The IWW is 115 years old but is still a new kid on the block in the UK, while the UVW was only founded in 2014 but now has 3,000 members. Given the structural changes in the British labour market, for the mainstream unions not to organise super-exploited precarious workers would be disastrous, limiting them to a bunker of the existing well-organised sectors. The success of these small unions stands as a rebuke to the larger, longer-established unions.

I feel the spirit of 1889 is in the air, when the dockers and match-factory women broke the mould of the old craft-based trade unions and breathed new life into the workers’ movement. If existing unions miss the opportunity, new unions will spring up to fill the gaps.

November 25, 2020