By John Pickard

In a movement with revolutionary significance, millions of workers and youth have continued to defy the ban on strikes and protests in Myanmar. This is despite growing threats from the military and the shooting dead of two protesters last weekend.

On February 1, the military – known as the Tatmadaw – seized power, arresting the state President, Win Myint, the state Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi and more than a hundred elected representatives of the National Democratic League (NLD) which had won a landslide majority in the parliamentary elections last November. The military declared a one-year ‘state of emergency’ and promised new elections, but popular credibility in this commitment is negligible.

After previous military coups, in 1962 and 1988, the military brutally crushed all opposition movements, banned trade unions, imposed martial law and imposed house arrest on opposition leaders. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that few in Myanmar takes the military at their word. Since the coup there have been non-stop protests the length and breadth of the country.

Escalation of military crackdown

Strikes have taken place in every region, shutting down workplaces, including the Tatmadaw-controlled Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, Myanmar National Airlines, railways and public transport, schools, colleges, mines and government ministries as well as construction sites and garment factories.

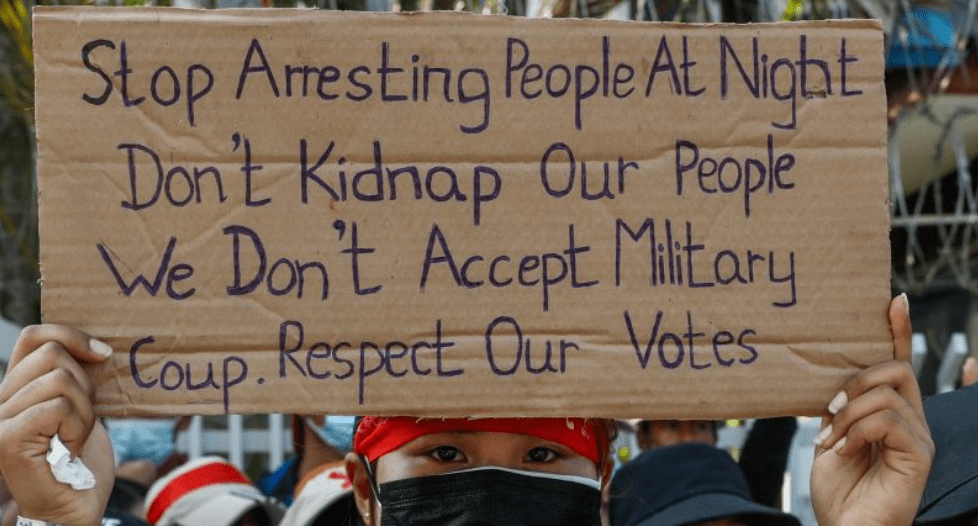

In response to the protests, the last three weeks has seen an escalation in the clamp-down by the military. Dozens of activists and protest leaders have been spirited away in the night. As the Myanmar Frontier reports, “It has become a sad ritual of life in post-coup Myanmar: scanning Facebook each night for reports – even livestreams – of the latest arrest of an activist or dissenting civil servant”.

“Grainy videos show armed military and police officers in the dark of night urging suspects to leave their homes, using a phrase – “kanar lite ke par”, (“please come with us for a moment”) – that has historically been associated with arrests of dissidents”.

But workers are pushing back. In many towns and cities, but especially Yangon (formerly Rangoon) and Mandalay, residents have been successful in foiling arrests by livestreaming military raids on social media.

Getting around the internet ban

The military have responded to the demonstrations and social media by frequent internet blackouts. Almost every day, the internet is cut overnight and restored the following morning, but this has not stopped the wave of protests. Not all of the internet services available have been banned and, in any case, many young workers – probably more ‘tech-savvy’ than the military – have been able to use software on phones to get around it. With the right app, blue tooth, which is a feature of all modern phones, allows phones to effectively operate as walkie-talkies to pass around messages and videos.

So the restrictions on the internet have not stopped the protest movement. In an article in the Myanmar Frontier newspaper, one journalist wrote, “The Tatmadaw underestimated the social forces that are coming together to resist the coup, and it will ruin the country and itself if it fails to negotiate a way out of its own mess.”

Myanmar is the former British colony of Burma, and it has been under military rule for most of the eighty years of its independence. It was the former Burma Independence Army that wrested independence from Britain and formed the basis of the modern military council, the Tatmadaw.

Where former military leaders tried to manage the economy through nationalizations and an element of economic planning, since that time most nationalized industries have been re-privatised and the current military are up to their necks in shady deals and corruption. Their governance of the economy has led to ruin, chiefly in public services where the military has no expertise whatsoever, like education and health.

Ethnic cleansing of over half a million Rohingya

Generations of ethnic minorities and indigenous communities have suffered the indignities and oppression of military rule. Most recently, we have seen the appalling ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya people, half a million of whom have been driven from their land and homes and now live as desperate refugees in Bangla Desh.

But whereas the military clearly expected a relatively easy ride – intimidating political leaders and especially the leaders of the NLD – it appears they have been taken by surprise by the huge groundswell of opposition to the coup. This is not 1988, and the class balance of forces has shifted decisively in the last thirty years in favour of the working class.

Monday saw the biggest protest yet, as a general strike rocked the country. Millions have joined workers in protests, including students, doctors, engineers, bank staff, lawyers, civil servants and even the police in some places. A civil disobedience movement has developed – with CDM now inscribed on many banners and placards in all demonstrations – that has snowballed beyond anyone’s expectations.

General strike Monday

Before the general strike, the military issued a chilling warning, that “confrontation” would “cost more lives”, but it did not deter the millions who took strike action. As one worker commented to a Myanmar newspaper, “If we oppose the dictatorship, they might shoot us. Everyone knows it. But we have to oppose dictatorship. It’s our duty. That’s why so many people are coming out today against them.”

It is still too early to say where this movement will go or what actions the military might take. Their options are extremely limited. If they back down and allow the elected NLD movement to take office – or even if they call fresh elections – there could be a tidal wave of demands for the military to be removed permanently from civil political life. But that would mean the end of the perks, privileges and graft with which they are tainted and for that reason, it is an option they are desperate to avoid.

There is no doubting the courage of the workers and youth and the scale of the protests. The international labour movement must extend its greatest possible support for their struggle for democratic norms and rights. Socialists around the world are hoping that that the movement maintains its momentum, and more, that it succeeds not only in restoring democracy to Myanmar, but that it moves towards expropriating the corrupt owners of land and industry. A socialist Myanmar would be a beacon to workers and youth right across southern Asia.

There still remains a danger, however, that the military will further escalate their bloody clamp-down; as much as they are a reactionary and counter-revolutionary movement, they may have some advantage over the protesters in being a clearer about their aims and their goals in the short term.

Youth are furious at being ‘robbed’ of their future

But there is no guarantee that the military can stifle the protests, much as they would like to. As one correspondent wrote in the Myanmar Frontier: “Even if it manages to quell demonstrations, popular resentment will morph from the creative, thoughtful, and passionate public protests we see today into more chronic forms of resistance, led by a generation of young people who are more connected and more exposed to the world, and who have experienced what is possible under a more democratic, liberalised and globally integrated Myanmar. They are now furious at the daylight robbery of their future.”

The economic perspectives for Myanmar are not good. The country is already suffering from a coronavirus-induced economic slump. The country, even before Covid, had a per capita GDP of $1,105, one of the lowest in southern Asia. Its poverty rate, at 37.5 percent, is one of the highest in the region. Among ASEAN countries, Myanmar has the lowest life expectancy and the second-highest rate of infant and child mortality.

Economic facts on the ground are unforgiving, and the military, desperate as they are to hang onto their privileges and power, have nothing to offer the mass of the population in economic policies. They will get no cooperation from workers, white collar workers, professional workers, or even small and medium-sized businesses and they will be found wanting. Of the total Myanmar population of nearly sixty million, half are under 25 years old. They will not be cowed for long, even if the military did succeed in temporarily dampening down the protests.

Even as a movement that is fighting to maintain its elementary democratic rights, the magnificent struggles in Myanmar are an inspiration to workers and youth across southern Asia and the world. But if that movement progresses in the direction of social revolution, expropriating land, oil, industry and big business under democratic control, it would have twenty times the effect on workers internationally; it would be a movement that would spread its influence even further and wider.