By John Pickard

1921 was an auspicious year, full of important political events, both nationally and internationally. It is fitting that serious socialists mark the centenary of those events, sometimes in celebration, but sometimes with the simple aim of studying and learning the lessons of past failures.

The so-called ‘March Events’ of Germany 1921 fall into the latter category. They were a series of events that demonstrated a failure to understand the temper and strength of the working class in a given time and place, and ultimately, therefore, a failure of leadership.

For more than two years after the November 1918 revolution, Germany had been racked by one revolutionary crisis after another. January 1919 saw the crushing of a premature uprising by workers in Berlin, in what became known as the ‘Spartacist Uprising’, and the following year, an attempt at a right-wing coup – the Kapp Putsch – was defeated by a spontaneous general strike and a mobilisation by armed workers’ militias throughout Germany.

In the early weeks of 1921, Germany’s national and international situation was still precarious. Germany was drained economically by the drastic reparations imposed by the Versailles Treaty and its workers were exhausted by months of political upheaval. Despite these convulsions, or because of them, the temper of the working class had subsided somewhat and there was now a mood of recovery, of drawing breath and preparing for the inevitable battles in the future.

Social-democracy still had a powerful hold on most workers

What the more revolutionary elements in the workers’ movement tragically failed to take into account, was the need to win mass support among those millions of workers who still gave their allegiance to the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Independent Social Democrats (VSPD).

After the revolutionary events of 1918, effectively ending German participation in the War, the German ruling class was only able to hang on by resting on the leadership of the SPD. The SPD leadership actively collaborated with reactionary militias in shooting down workers in January 1919, and many times later. Yet, in government, they were still able to garner support among millions of workers, by reforms to the working day, improvements in workers’ housing, in welfare and in other respects. Despite their monstrous betrayal in supporting the war in August 1914, and despite their equally abhorrent betrayal of the revolutionary movements at the end of the war, by 1921, the SPD leaders still commanded huge support among workers, in fact far more than the Communists. The SPD still had many daily newspapers with a wide readership, as well as offices, full-time officials and a large apparatus.

In the Federal election in June 1920, for example, the combined SPD and VSPD vote was 39%, compared to the Communist Party’s 2%. Even in Prussia, considered a bastion of the Communist Party, in the state election of February 1921, the SPD and VSPD together got 33% of the vote, to the Communist Party’s 7.4%.

Divisions between right and left in the Communist Party

This was the background to attempts that were made to unify the revolutionary Marxist elements in Germany into a single Communist Party, under the guiding hand of the Communist International (Comintern). The unification was not entirely successful, however, and alongside the United Communist Party of Germany (VKPD) there was still a smaller Workers Communist Party (AKPD) as well as other groups.

Significantly, the VKPD was itself riven with divisions between its ultra-left and ‘rightist’ wings which differed over key issues. In early 1921, there were differences over the split that had happened in the Italian Communist Party and one of the founders of the UKPD, Paul Levi, first resigned from the leadership (in February) and was later expelled. In subsequent events, key roles were played by representatives of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) who were active in the leadership of the VKPD, attending its leading committees; these were principally, Karl Radek and Bela Kun.

The October Revolution stood behind the authority of the Comintern

It has to be borne in mind that the Comintern was an organisation with tremendous authority among the best sections of the German labour movement, because it rested on the authority of the Russian Communist Party and the October Revolution. What Radek and Kun said, therefore, counted for a lot, and they played an important role in promoting what was a disastrous ultra-left view, leading to the events in March.

In his book, the German Revolution 1917-23, (without doubt the best book on this period in Germany) Pierre Broué described the role played by these emissaries from the Comintern. “the VKPD was passing through a severe crisis, the proof of which was the fact that it did not act and merely confined itself to discussion, at a moment when nothing but action would have highlighted the problems of the day. Radek gave the impression that the ECCI wanted to ‘activise’ the VKPD.”

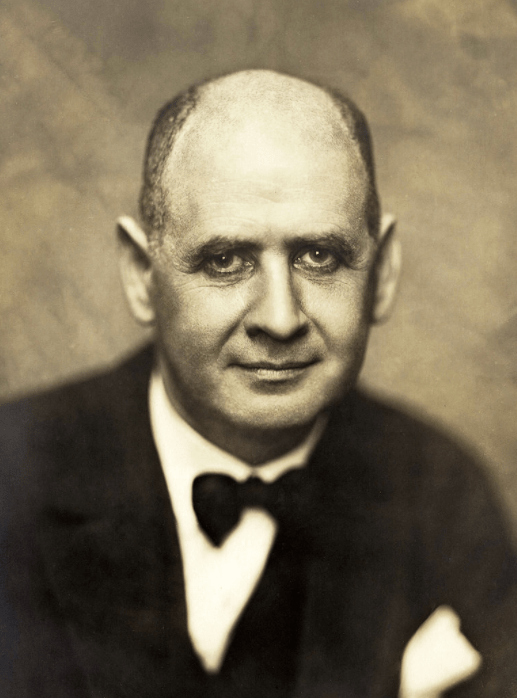

Bela Kun was one of the main proponents of the ultra-left theory of the ‘revolutionary offensive’, suggesting that activity alone could be sufficient to arouse masses of workers into revolutionary struggle. Kun and Radek actively promoted the idea that the balance of class forces in Germany could be changed merely by the activity of the Communist Party itself.

As well as their failure to find a way to win over the large numbers of social-democratic workers, there were critical political issues looming in the background, which directly and dramatically affected the workers’ movement. The world powers who had emerged victorious from the First World War – the Entente, composed principally of the USA, Britain and France – were demanding that the German government disarm all workers’ organisations (many still retaining arms from the war) and the extension of the area of Germany occupied by the victorious powers, thereby increasing their stranglehold on the German economy.

Plebiscite planned in Upper Silesia

The Entente also demanded the disarming of the Orgesch, a far-right paramilitary group, not because of its political leanings – they were more than happy to see Orgesch attacks on workers’ organisations and strikers – but because it threatened to undermine the German ‘de-militarisation’ that Versailles demanded.

There was also the question of Upper Silesia, an important industrial area to the South East, with a mostly German population, but which had been ‘granted’ to Poland in the Treaty of Versailles. A plebiscite had been arranged for March 20, but long before then Polish military units had begun to occupy parts of the territory and the German government responded with unofficial, overwhelmingly right-wing, militias which occupied other areas. Inevitably, there were clashes between the two, with German workers caught in the middle. The Entente demanded that these German units also be disbanded.

Compounding all these crises, the Oberpräsident of Prussian Saxony, the Social Democrat Hörsing, announced that several key industrial zones were to be occupied by the police, including the mining district of Mansfeld-Eisleben. Hörsing’s real aim was to disarm those workers who had kept their weapons after the Great War and had brandished them again – threateningly, in the eyes of the ruling class – in the failed Kapp Putsch the previous year. It was a direct challenge to workers in what was a Communist stronghold.

Despite these gathering crises, however, there were no indications that workers across the whole of Germany or that SPD-supporting workers were prepared or ready for a new revolutionary wave. The relatively new Communist Party did not have the necessary authority and support among enough German workers to make a decisive difference. It had support, but as to whether that was enough, and across the whole of the working class, remained to be seen.

Changing the relationship of forces by ‘action’

The promptings of Radek and Kun, therefore, ran against the grain, as far as the mood and temper of most German workers were concerned. Nevertheless, through these representatives of the Comintern, Broué argues, “The German Communist leaders were to be taught that their Party could change the relation of forces by an active intervention…”

The provocation of Hörsing was seized on by Radek and Kun as the opportunity to ‘activise’ the German working class. The Communist Party leaders in that part of Saxony were given orders from the centre to call a general strike as soon as police occupied a factory, and they were at once to prepare for armed resistance. “A draft statement appeared in [the VKPD newspaper] Die Rote Fahne for the following day, March 18, calling for the workers to be armed…justified by the refusal of the Bavarian government to disarm and dissolve the counter-revolutionary organisations of the Orgesch”

On March 20, as police units began to be deployed, Die Rohte Fahn went on to call for workers everywhere to support their brothers and sisters in Central Germany. On March 21, strikes began to develop in areas occupied by the police. However, the call by the VKPD for a general strike on March 22 in the province met with only partial success. “Reality,” Broué writes, “did not correspond to the expectations of Kun and his supporters.”

One of the leading ultra-left Communists, according to Broué, “explained to local leaders that they must at all costs provoke an uprising in Central Germany, which would be the first stage of the Revolution. No means could be ruled out for shaking the workers out of their passivity, and he went so far as to suggest organising faked attacks on the VKPD or other workers’ organisations or kidnapping known leaders in order to blame the police and the reactionaries, and in this way provoke the anger of the masses.”

Calls for a general strike went unheeded

In the following two days, small groups of armed workers went onto the offensive, in what could only be described as ‘guerrilla’ tactics. Here and there, police units were attacked or were disarmed.

Across the rest of Germany, the VKPD made efforts to gather support for the struggle in Saxony. In Berlin, there was a demonstration and a meeting to call for a general strike, but both were poorly attended. In Hamburg on March 23, there was a demonstration of unemployed workers, again demanding a general strike and occupying a part of the docks. The Communists called for a general strike across the whole of Germany.

Where there was clearly a reluctance to follow the strike call, groups of Communists tried to provoke actions, by occupying factories and denying entry to non-Communist workers who wanted to work. Groups of unemployed Communist Party supporters clashed with workers trying to get to work. The general outcome of the strike call was modest, according to Broué, with perhaps as few as 200,000, and half a million at the most, on strike. In Berlin, where the strike was practically non-existent, a joint demonstration of the KAPD and the VKPD in the Lustgarten attracted fewer than 4,000 participants.

Long after it was clear that the general strike call had fallen on deaf ears – on April 1, in fact – the VKPD ‘called off’ the non-existent strike.

Completely misunderstanding this failed movement, the Moscow editors of the Communist Party newspapers hailed the struggle of the German workers. Pravda, on March 30, under the heading of ‘The German Revolution’, saluted the German workers, giving the impression that they were on the attack, with a combination of strikes and armed uprisings.

In fact, the VKPD had inflicted a disaster on the party. Thousands of workers walked away in disgust and many links between the Party and industrial workers – forged in the titanic struggles of 1918-20 – were broken. In a few weeks, the Party lost around 200,000 members. As a result of the March events, in the next two months, Broué reports, “400 workers were sentenced to a total of 1,500 years hard labour, 500 to 800 years in jail, eight to life imprisonment and four to death.” Tens of thousands of workers were victimized and subsequently blacklisted.

The March Days demonstrated tragically that it is not possible for revolutionary leadership to ‘leap’ over or ignore the concrete objective conditions in which they find themselves or their lack of support among the mass of workers. No amount of provocation, ‘super-activity’ or shrill calls to action can compensate, if the mass of the working class are unwilling to engage in struggle at that juncture.

The mistake of 1921 compounded by 1923

It took a long time for the lessons to be learnt in the VKPD and even in the Comintern. It is arguable that the ultra-leftism of the ‘March Days’ was a main contributary factor in the later passivity of the Party leadership in October 1923, when there was indeed a revolutionary situation. From ultra-leftism, in two and a half years, the leadership swung too far in the opposite direction.

In fact, in the entire period of its existence before the take-over by the Nazis in 1933, the Communist Party was never at any time to adopt a successful tactic that was likely to win over the mass support or membership of the SPD.

It is also clear that the leaders of the Russian Revolution, and the only theoreticians of real stature in the Comintern in 1921, Lenin and Trotsky, were so preoccupied by other pressing issues that they could have been not be completely aware of the background to the March events or the processes as they unfolded.

In the aftermath of this disaster, the disputes within the VKPD were renewed with even greater ferocity and the acrimony eventually led to Paul Levi, after vigorously denouncing the March action, moving away from the Communist Party, rather than fight for his position inside it. It was in mid-April, largely unaware of the splits and furious polemics in the German Party, that Lenin drafted a letter to Paul Levi, in which he wrote,

“As for the recent strike movement and the action in Germany, I have read absolutely nothing about it. I readily believe that the representative of the [Comintern] executive committee defended the silly tactics, which were too much to the left – to take immediate action ‘to help the Russians’: this representative is very often too left. I think that in such cases you should not give in, but should protest and immediately bring up this question officially at a plenary meeting of the executive bureau.”

Comintern Congress in June 1921

Not surprisingly, at the June Congress of the Communist International, the ‘March action’ was a key discussion, and one in which the German delegation and Radek continued to support the illusion that the VKPD had followed a broadly correct policy.

At the Congress, the criticism of the German Communist Party was relatively muted, because the leaders of the Comintern did not want to subject the party to such a withering condemnation that it was crushed. But in his address in the session on Germany, Trotsky clearly described the actions of the VKPD as a “blunder”.

He first gently reprimanded the German delegation. “One gets the impression”, Trotsky he said, “that the members of the German delegation still approach the issue [the March events] as if it had to be defended at all costs, but not studied nor analyzed. And everything that we hear is, so to speak, a means towards an end – which is to defend the March action at any price…”

But then he spelt out in more detail his criticisms: “The Congress must say to the German workers that a mistake was committed, and that the party’s attempt to assume the leading role in a great mass movement was not a fortunate one. That is not enough. We must say that this attempt was completely unsuccessful in this sense – that were it repeated, it might actually ruin this splendid party.”

Lenin was scathing in private criticisms

Where the criticisms in the open sessions of the Congress were somewhat tactful, in private, the leaders of the Russian Communist Party, and especially Lenin, were scathing. In his Memoirs of a Revolutionary, Victor Serge, described the private discussions around the time. “At a meeting of the Executive of the International,” he wrote, “Lenin made a lengthy analysis of the Berlin affair, this putsch initiated without mass support, serious political calculation, or any possible outcome but defeat. There were few present, because of the confidential nature of the discussion.

“Bela Kun kept his big, round, puffy face well lowered; his sickly smile gradually faded away. Lenin spoke in French, briskly and harshly. Ten or more times, he used the phrase ‘les betises de Bela Kun’: [Bel Kun’s stupidities/follies] little words that turned his listeners to stone. My wife took down the speech in shorthand, and afterwards we had to edit it somewhat: after all it was out of the question for the symbolic figure of the Hungarian Revolution [Kun] to be called an imbecile ten times over in a written record! Actually, Lenin’s polemic marked the end of the International’s tactics of outright offensive”.

Activity in the workers’ movement is always a dialogue

The significance of the March days lies not only in its historical interest, although there is that. It lies in the fact that there are many groups on the left today, including some who describe themselves as Marxists, who take no account of the real and concrete mood of the working class and the circumstances in which they work. Political activity in the labour movement must always mean a dialogue, not only with immediate comrades and like-minded socialists, but with workers in general, in all industries, types of workplace and in all areas. Listening to workers to gauge the real mood of the labour movement is as essential as speaking in the language of socialist policies. There are no short cuts to winning mass support for socialist ideas.

Had the German Communist Party in March 1921 really gauged accurately the consciousness of the class and understood the temper of workers across the whole of Germany at that time, then things might have been different. Had the Communists developed a strategy and tactics that could realistically win over social-democratic workers, then perhaps the whole history of Germany after that point would have changed.