By Michael Roberts

There is much talk among ‘progressive’ economists that the IMF and the World Bank have turned over a new leaf. Gone are the days of supporting fiscal austerity, demanding that national governments get public debt levels down and insisting on conditions for countries borrowing IMF-WB funds that their governments privatise their state assets, deregulate markets and reduce labour rights.

Now after the experience of the unprecedented COVID pandemic slump, the old ‘Washington Consensus’ is over and has been replaced by a new ‘consensus’. Whereas the ‘Washington Consensus’ for international economic policies of the 1990s saw government failures as the reason for poor growth performance and advised governments ‘to get out of the way’ of market forces, now the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation’s chiefs call for more fiscal spending, more funds for lending, and measures to reduce inequality between nations and within nations through higher taxes on the rich.

Such ‘progressives’ like Martin Sandu in the Financial Times are excited by this change of heart and policy.“Back in the ‘90s, it was a truism the Washington consensus reflected the aligned priorities of two DCs: the international institutions based there and the US government — with the latter to a significant degree driving the former…but it is hard to argue today that the IMF and the World Bank simply parrot US preferences.”

IMF rhetoric certainly seems different

And the rhetoric of the IMF and World Bank as posed by the likes of IMF chief Georgieva certainly seems different. Throughout the virtual Spring meeting of the IMF-WB last week, and on the IMF blogs, the message was that more fiscal stimulus was acceptable and necessary, and rising public debt was tolerable while the COVID crisis is dealt with. This appears to be the opposite of the IMF-WB policy message after the Great Recession of 2008-9, when these international agencies called for balanced budgets and reduced debt levels. For example, the IMF backed the draconian conditions imposed on Greece during its debt crisis in 2012-15 that led to a 40% reduction in average living standards there.

Now Georgieva’s IMF policy agenda sounds different. Global Policy Agenda “Policymakers must take the right actions now by giving everyone a fair shot. That includes a fair shot at accessing the vaccine, a fair shot at support during the recovery, and a fair shot at the future in terms of participating and benefitting from public investments in green, digital, health and education opportunities. “Economic fortunes are diverging dangerously. A small number of advanced and emerging market economies, led by the U.S. and China, are powering ahead—weaker and poorer countries are falling behind in this multi-speed recovery,”she said. “We also face extremely high uncertainty, especially over the impact of new virus strains and potential shifts in financial conditions. And there is the risk of further economic scarring from job losses, learning losses, bankruptcies, extreme poverty and hunger.”

What’s the answer now? The IMF proposes more debt relief, ie delaying repayments on existing loans made to poor countries and reducing interest costs through to 2022. At the Spring meeting, it was also announced that IMF funding based on Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) liquidity approved by the key member states would be increased by SDR500bn. So extra funding firepower.

Has the policy really changed?

But has the IMF-WB policy consensus really changed? Has the commitment to free market forces and fiscal stability in return to conditional loans to desperate countries really been dropped? The new consensus, if it really exists, is one of necessity, not change in ideology. Just as governments in the major capitalist economies have been forced to let the fiscal taps flow and inject humongous amounts of credit into the economy to avoid a total meltdown in the COVID slump, so the IMF-WB have seen the necessity to try and avoid a global debt disaster as governments of poor countries around the globe default on their debts to banks and other international financial institutions.

I have posted several times on the impending emerging market debt disaster and the IMF-WB is well aware of this. But when we dig down below the rhetoric and examine the terms that the IMF and the World Bank are still holding to on existing loans and future ones, little has changed. As a recent incisive report by the International Trade Union Confederation ITUC) comments: “The “new” IMF says it has changed and supports a green and inclusive recovery but keeps acting a lot like the old IMF. …market fundamentalism still underpins the IMF’s growth narrative and advice”.

And the ITUC points out that the IMF ‘conditionalities’ were unsuccessful in helping poor countries out of the economic difficulties into sustained growth. On the contrary: “A close look at the IMF’s growth narrative shows that claims about the benefits of many preferred policies are overblown while the negative effects are well documented. Countries that have successfully moved up the income scale over the past decades did not follow the laissez-faire prescriptions of the IMF. Thus, it is not a track record of results but engrained market fundamentalism that underpins the IMF’s policy advice.”

COVID emergency lending has not been significant

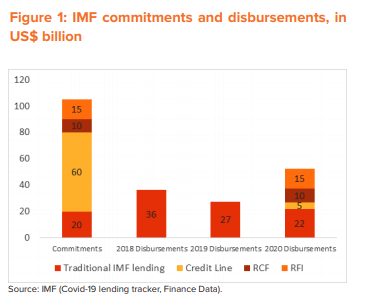

Indeed, emergency lending needed during the COVID slump has not really been significant in IMF largesse. “Out of the committed assistance, the largest part is in the form of pre-approved credit lines offered to Peru, Chile, and Colombia. Only Colombia has utilised its credit line thus far. The disbursements through rapid emergency lending, which comprise the support offered to almost 70 countries, only amount to about $30 billion. Combined with traditional lending arrangements, the IMF disbursed about $50 billion to 81 countries in 2020. Disbursements for 2020 are only slightly larger than in previous years, when IMF assistance went to a much smaller number of countries.”

When you look at the IMF reports on new lending the supposedly new calls for more public investment are only directed to countries that have “fiscal space” ie ones that can afford spending anyway. The ITUC comments “in general, the IMF continues to recommend fiscal consolidation as a pillar of a medium-term fiscal strategies once the crisis is over.” In a survey of IMF staff reports for 80 countries, the European Network for Debt and Development found that 72 countries forecast cuts to spending levels below their pre-pandemic baseline as early as 2021, with all 80 countries doing so by 2023. And these austerity plans were met with approval from Fund staff.

IMF loans still in line with structural reforms including labour deregulation

The ITUC analysis shows that the IMF still follows a ‘supply-side approach’ to economic growth that “focuses on creating ideal conditions to attract private sector investment. The Fund commonly states that the goal of its advice is to boost “confidence” and “competitiveness”, leaving the rest up to markets.” A study of conditionality in IMF loan agreements between 1985-2014 confirms this pattern and finds that while the number of conditions in loans fluctuated over time, their content was consistently in line with structural adjustment programmes comprised of structural reforms including labour market deregulation, along with fiscal consolidation.

While the IMF and its advanced economy masters are allowing ‘debt relief’ and offering more funds, the cancelling of onerous debts already incurred by ‘global south’ economies engulfed in the pandemic slump is not being offered. So if there is a new ‘consensus’ on international lending and economic support by multi-national agencies it sits on the surface of talking; when the walking begins, nothing has really changed.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.