By Cain O’Mahony

May 3, 1921, saw one of the greatest modern tragedies in Ireland: its partition into a six-county ‘province’ of Northern Ireland, still part of the United Kingdom, and a twenty-six county Republic in the South.

The partition followed the massive upheaval and popular outrage at the suppression of the Easter Rebellion of 1916. That event was itself one of the greatest tragedies of the twentieth century, a premature rising in Dublin, largely by-passing the mass of the population, even in that city itself. As heroic as the Easter Rebellion was, it led to the execution of that giant of Irish socialism, James Connolly, and it shattered the last remnants of his Irish Citizens Army, a potentially revolutionary force of armed workers. At this, the hundredth anniversary of Partition, it is important to examine how this loss plunged Ireland into decades of conflict.

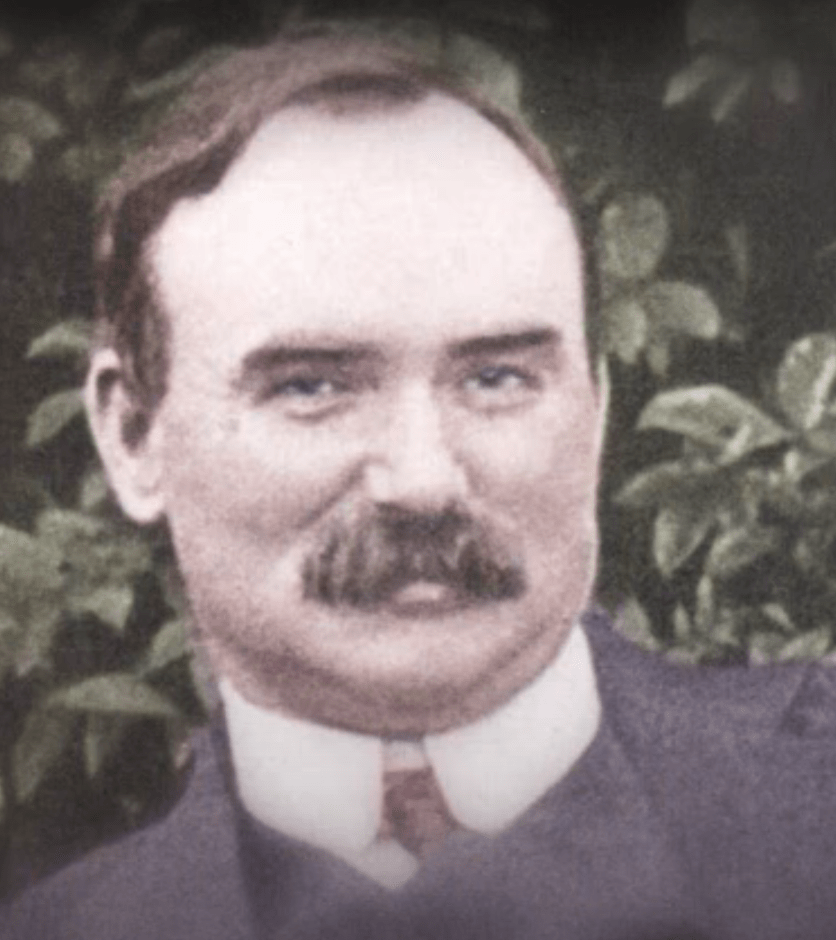

James Connolly was a Scottish trade unionist, born of Irish parents, who was blacklisted after standing as a Labour candidate in Edinburgh. He became active in Ireland, founding the Irish Socialist Republican Party, then he spent seven years organising workers in the United States with the IWW. He then returned to Ireland, summoned by trade union organiser, James Larkin, to help in unionising the lowest paid and exploited section of the working class in the British Isles.

Ruling class shaken

Larkin had already sent shockwaves through the British Imperial establishment by uniting Protestant and Catholic workers in Belfast in the dock and transport strikes of 1907. The ruling class were shaken, after their age-old method of ‘playing the Orange card’ to divide the workers had totally failed. As Connolly commented in his marvellous book, Labour in Irish History, “…the presence of a common exploitation can make enthusiastic rebels out of a Protestant working class, (and) earnest champions of civil and religious liberty out of Catholics, and out of both a united social democracy”.

There was a further momentous struggle in 1913, with the great Dublin Lockout. After a series of successful strikes, Jim Larkin and Connolly’s Irish Transport & General Workers Union began to organise the United Tramway Company. Its owner, William Murphy, who also owned much of Dublin’s media, called together 400 of the city’s employers and they joined him in locking their factory gates to any who belonged to the trade union.

Despite six months of hardship and ferocious police attacks which left three dead and hundreds badly injured, over 100,000 workers stood by Connolly and Larkin, until they were literally starved back to work. The struggle had become isolated, after the sympathy strikes that broke out in Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham were disgracefully shut down by the British TUC leadership, who then confined British trade unions to only fund-raising for the ITGWU.

This massive defeat was then compounded by the outbreak of World War I. By 1916, the ITGWU had seen its membership and funds dwindle: Larkin was dispatched to the USA to raise money – unfortunately, his visit coincided with the huge purge of the US labour movement by the American state, and Larkin was imprisoned in Sing Sing gaol until 1922.

The killing fields of France

By 1916, the prospect for the Irish working class looked remarkedly bleak and was now set to be compounded by the threat by the British government to impose mass conscription in Ireland for the killing fields of France. It was bad enough to be a subjugated people, but now they were expected to die for their oppressor too.

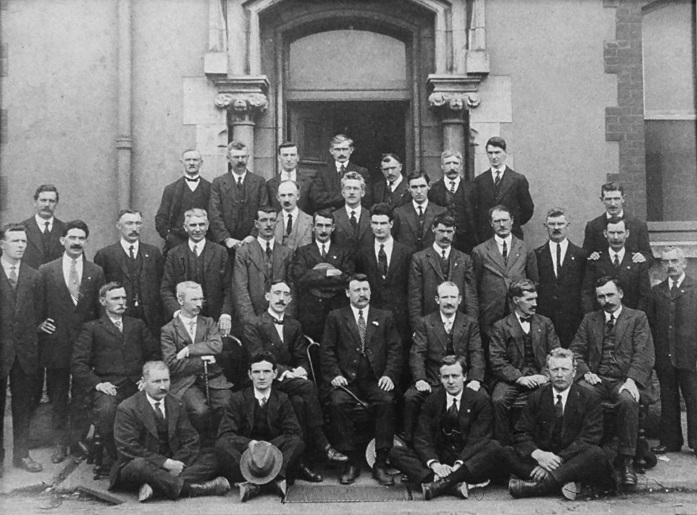

In desperation, Connolly joined with the ‘physical force’ Nationalists of the Irish Volunteers who also understood the immediate threat of mass conscription, though this time to their goal of an Irish Republic. Connolly took his small cadre of the Irish Citizens Army (see picture above) – formed in 1913 to defend picket lines against police attack – to fight alongside the Irish Volunteers for the ill-fated Easter Rebellion.

Connolly had no illusions about the policies of the Nationalists, telling Citizen Army volunteers a week before the uprising: “The odds are a thousand to one against us. If we win, we’ll be great heroes; but if we lose, we’ll be the greatest scoundrels the country ever produced. In the event of victory, hold onto your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting [ie their ‘allies’ among the nationalists’] may stop before our goal is reached. We are out for economic as well as political liberty.” (C Desmond Greaves, The Life and Times of James Connolly)

The ill-timed uprising received little support and was swiftly crushed by the British Army. The consequences were disastrous. It played into the hands of labour’s enemies in the North of Ireland, who would forever link socialism to Irish Nationalism to scare Protestant workers away from revolutionary ideas. With the removal of the best elements of the Irish labour movement, it also gave a free hand to the Nationalists whose demagogy would go unchallenged. But most of all, it was premature, and removed a potentially powerful revolutionary cadre, the cream of the labour movement, from this stage of Irish history, and from the events that would begin to unfold the following year.

Citizen Army could have played key role in 1918-20

Connolly was reviled by right-wing labour leaders internationally for his action, from the British labour leaders through to Plekhanov in Russia. Only the ‘Zimmerwald Conference’ leaders, and Lenin and Trotsky in particular, stood by him. In an essay on the lessons of the events in Dublin, Trotsky wrote: “… the historical role of the Irish proletariat is only beginning. Already it has brought its class anger against militarism and imperialism into this rising, under an out-of-date flag” (Lessons of the Events in Dublin, 1916).

Unfortunately, the removal of Connolly, Larkin and cadre of the Citizen Army, which could have played a key role in the events of 1918-20 – meant the workers continued to take up the struggle under that ‘out-of-date’ flag.

After the brutal suppression of the Easter Rebellion, British Imperialism thought the ‘Irish Question’ had been put to bed for the foreseeable future and they could focus on the war in Europe. They were oblivious to the sea-change that was beginning to happen in the consciousness of Ireland’s workers. While few had joined the Rebellion, there was outrage across Ireland at the treatment and the summary execution of its leaders. Connolly was the last to be shot in Kilmainham Prison, brought straight from hospital where he had been treated for serious wounds, and shot whilst tied to a chair to keep him upright.

Trade union membership began to rocket

The anger was evident in 1917, when Sinn Fein, a new radical nationalist party, won four by-elections. At the same time, trade union membership began to rocket. In 1916, the National Union of Railwaymen had just 5,000 members in Ireland, but within nine months, it had risen to 17,000. In 1917, the trade union of Connolly and Larkin, the ITGWU, had just 5,000 members, but, reorganised, it began recruiting. All new members received a free copy of Connolly’s pamphlet, Socialism Made Easy. By 1920, the ITGWU had 120,000 members. In October 1917, around 3,000 workers were on strike in different disputes in Dublin. Between 1917 and 1920, there were 18 general strikes in different towns around Ireland.

As Irish society was clearly coming to the boil, British Imperialism blundered into blowing the lid off. Facing a dire lack of troops on the Western Front after the calamity of the German Spring Offensive of 1918, the British government finally announced mass conscription for Ireland. It was met with an immediate and effective one-day general strike across the South on 23 April. People began attending Sinn Fein rallies in their thousands.

British Imperialism blundered on. They fabricated a ‘German Plot’, alleging that Sinn Fein were conspiring to bring in weapons from Germany for a new uprising and they arrested 73 leading party members. This attempt to behead the movement caused fury, many noting the fact that when the Protestant Ulster Volunteer Force was formed in 1914 – to stop Home Rule – it was provided with 25,000 rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition by Germany. Yet not one UVF leader was arrested. Nonetheless, the War for Independence had begun, and the Irish Republican Army was formed.

Economic ‘liberty’ and not just national liberty

The struggle for national liberation sparked a massive social movement because, as Connolly had demanded, workers were demanding economic and not just national liberty. For many, the struggle was not seen as separate, but as an extension of the ideas of the Russian Revolution.

Particularly in rural areas, between 1919 and 1921, Dail Courts (or Republican Courts) sprung up across the country. People had never trusted ‘British justice’ and as far back as 1880, had established their own courts to resolve land or other disputes. Now they became vehicles for the redistribution of land, cattle and wealth, mainly in the west of Ireland, with wide-scale land seizures (there is an excellent portrayal of a Dail Court in action in Ken Loach’s excellent film, The Hand That Shakes the Barley).

The British and Unionist landed gentry were dealt with too, and during this period 192 stately homes were attacked and burnt down, and often their extensive ranches and estates redistributed by the Dail Courts. For the advanced layers in the industrial working class, this was the beginning of the socialist revolution, and the goal was a Workers’ Republic.

In Leitrim, the miners took over the Argina coalfields. In Limerick, thirteen creameries were taken over, and a soviet declared, even producing its own currency – ‘Labour Notes’. In the main creamery in Knocklong, a Red Flag was hoisted with a banner declaring ‘We make cream, not profits. Knocklong Creamery Soviet’.

There were similar soviets formed in County Claire, with the Buree Flour Mills also hoisting banners declaring ‘Soviet Mills – we make bread not profits’. Beside the general strike against conscription, there was a further three-day general strike against the imprisonment of Republican leaders, while workers in the docks and railways refused to handle ammunition and supplies for the occupying British Army.

No leaders of the calibre of Larkin or Connolly

Unfortunately, this unfolding revolution did not have a labour leadership of the calibre of Connolly or Larkin. Instead, the Labour leadership allowed themselves to become an auxiliary of the nationalists of Sinn Fein, who represented the rising capitalist class and upper middle class – those who would supplant British Imperialism in the new state.

A sign of the class antagonisms to come was seen at the Cork City creamery in 1920. A strike there by members of the ITGWU saw their pickets stop deliveries of milk. Local Nationalists commanded the IRA to break the strike and disperse the pickets. Fortunately, many of the IRA volunteers ordered to carry out the task were also members of the ITGWU, while many of the pickets were also members of the IRA. The rank and file of both sides took the dispute to a Dail Court and a settlement was reached. But it was a warning of whose interests some of the Sinn Fein leadership prioritised.

These right-wing nationalist elements, though, were still haunted by the spectre of Connolly and the legacy of his support amongst the working class. They were therefore obliged mouth left wing slogans. Even the nationalist leader, De Valera, declared on the election trail: “If I were asked what statement of Irish policy was most in accord with my views as to what human beings should struggle for, I would stand side by side with James Connolly.”

The labour leaders fell for such lip-service, and in the crucial 1918 General Election, De Valera demanded that the Labour Party – formed in 1912 through the intervention of Connolly – should stand aside to allow Sinn Fein a free run, under the slogan: ‘Labour must wait!’ Unfortunately, they did exactly that.

Sinn Fein received massive support, with many of its members being elected even while in prison: such as Sean O’Mahony, a founder of the Irish Volunteers, elected MP for Fermanagh South in the North while serving his sentence in Lincoln prison. Across the whole of the island of Ireland, Sinn Fein won 73 seats out of 105.

Revolutionary struggles across Europe

These events terrified British Imperialism. Across Europe, capitalism had been shaken by the Russian Revolution, and revolutionary struggles were now ripping across Germany and Central Europe. Three long-standing imperial dynasties had been overthrown, in Russian, Austro-Hungary and Germany. Britain in 1919 faced an upsurge in class conflicts, from the Red Clydeside revolt in Scotland to the mutinies by British soldiers demanding demobilisation in France.

It was these fears that drove British Imperialism to enact the partition of Ireland. There were of course immediate material considerations. They wanted to retain the more profitable heavy industries of the North, and, from a military-strategic point of view, to maintain the northern Irish ports to protect Britain’s Western flank from its European rivals.

But its prime motivation was that a partition would act as a brake on the growing revolutionary social movement emanating from the South. On May 3, 1921, they enacted the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which split Ireland into two, imposing a Northern Ireland House of Commons at Stormont and a Southern Ireland House of Commons (immediately renamed the Dail Eireann), with the offer for Southern Ireland to become a Free State.

The Assembly in the North, established a hundred years ago, was a fait accompli, and Ireland was split from that point on, but it was still many months before the South accepted partition. From the point of view of Britain, the tactic had been successful – it split the Republican movement in two. The closeness of the split could be seen in the Dail’s vote to accept the ‘Free’ State – 64 votes to 57.

A new election was called in the Free State in June 1922, and two ‘Sinn Feins’ stood. The Pro-Treaty SF received 240,00 votes and the Anti-Treaty SF 140,000. Significantly, demonstrating the legacy of Connolly and the depth of support for his ideas, the Labour Party received over 21 per cent of the total vote and only one thousand less than the Anti-Treaty SF. But unfortunately, again, the labour leaders had sat on the sidelines, offering little leadership.

As historian Michael Hopkinson comments: “Irish Labour and trade union leaders, while generally pro-Treaty, made little attempt to lead opinion during the Treaty conflict, casting themselves rather as attempted peace-makers” (Green Against Green, 1988).

The last straw for many of the Anti-Treaty forces was the new Dail refusing to allow Sean O’Mahony, the only Republican MP elected in what was now Northern Ireland, from taking his seat, because of the new Free State constitution imposed by British Imperialism, with O’Mahony being told to take his seat up in the Northern Parliament. Many saw this as the final abandonment of any quest for a united Ireland.

Vicious but short-lived civil war in the South

A vicious but short-lived civil war followed, but the Anti-Treaty forces were soon crushed, after British Imperialism supplied the new Free State with machine guns, artillery, aircraft and vehicles. The forces of the Free State used methods of repression against the anti-Treaty forces, including the murder of hostages, every bit as vicious as the British government had before them.

Connolly had warned that the partition of Ireland could lead to a “carnival of reaction” and nowhere was that perspective truer than in Northern Ireland in the succeeding decades of the twentieth century.

Displaced Scottish agricultural peasants and workers had originally been ‘planted’ in Northern Ireland by English monarchs in the seventeenth century, to act as a bulwark against the Catholic south, in the game of chess that was the Catholic-Protestant conflicts of the period. From the English Civil War through to the Thirty Years War, English monarchs feared that Ireland would be a back door for the invasion of Protestant England by its Catholic European enemies.

In the close of the eighteenth century, as the industrial revolution was beginning, the British ruling class had been rocked by the revolt of the United Irishmen, where Catholics and Protestants (its leader was a Protestant) had joined together in the fight for Liberty, a movement inspired by the French and America Revolutions. The new industrial capitalist class reinforced sectarianism to divide Northern Irish workers, using the Protestant ‘ascendancy’ to buy their loyalty. Divide and Rule was institutionalised.

A general strike unfolded across Belfast

The Orange bosses and the British ruling class had thought that the events of 1914 – where Edward Carson and the Unionists formed the Ulster Volunteer Force and threatened open revolt against Home Rule – had finally re-enforced sectarianism, immunising the Protestant workers against the radical ideas emanating from the South. Yet working class unity returned to Belfast in 1919. The North was not unaffected by class movements, not only in the South, but in Britain too, not least Red Clydeside, where the battle was on for the 44-hour week.

Following their lead, a general strike rapidly spread throughout Belfast, with the shipyard workers being led by a Catholic. The significance of the Belfast 1919 general strike, however, was that it awoke the consciousness of many Protestant workers, who moved onto the political plane – and towards socialism. Independent labour parties were formed – ‘Belfast Labour’ and the established Independent Labour Party – who for the first time, fielded candidates for the 1920 Belfast municipal elections, and stunned everyone by winning 13 seats, breaking the usual ‘sectarian headcount’.

If the movement in the South had been one led by Connolly and the ICA/ITGWU, with the clear offer of ‘economic liberty’ and even solidarity with ‘Red Clydeside’, at this crucial moment they would have found willing ears on the streets of Belfast for the idea of a Workers Republic.

Unionist press whipped up fear of Home Rule

Instead, faced with a potential social revolution in the South and a rising voice of independent labour in the North, the Belfast bosses and their sectarian lapdogs instigated vicious pogroms. The Unionist press whipped up fears about Home Rule and called on Protestants to expel not only Catholics but also “unreliable Protestants and Socialists” from the workplace.

Their call was answered by the Belfast Protestant Association, an extremist Orange group. Armed with sledgehammers and other weapons, they swarmed into the shipyards, factories and mills and attacked Catholics and trade unionists. By the end of the maelstrom, 9,000 workers had been beaten from their workplace, the majority of them Catholics, but also 2,000 Protestants, mainly trade unionists, who had attempted to defend their brothers. The aftermath of the 1920 pogroms was the end of trade unionism in Northern Ireland for the immediate future.

As Connolly had predicted, a ‘carnival of reaction’ was indeed being played out on both sides of the new border. In the South, the final crushing of the Anti-Treaty forces saw the establishment of an impoverished capitalist theocracy, where unemployment and low wages were matched only by the lack of basic human rights and welfare services.

Sectarianism my yet boil over again

In the North, Protestant workers were rewarded for their loyalty with drastic wage cuts and an unemployment level of 24 per cent by 1925, not to mention a seething cauldron of sectarianism and pogroms that has continually boiled over through the decades (the ‘Troubles’ of 1969-1994 left over 3,000 dead and 100,000 injured) and may yet boil over again as the Tories blunder around the issues of Brexit and the border.

The loss of Connolly and the beheading of the Irish labour movement in 1916 came only two years before the momentous events of 1918-20 which, with a dynamic socialist leadership, could have changed the course of history in Ireland, in Britain and possibly the world.

That was not to be. But it is the responsibility of socialists today to learn the lessons of missed opportunities and, as Connolly himself did, clearly distinguish between the interests of the ruling establishment, both Orange and Green, and the interests of workers.