By Michael Roberts

These notes were based on an interview with me by Swiss-based journalist Thomas Schneider in German in early May. See https://www.facebook.com/klaus.klamm.9235/

A sugar rush or economic recovery?

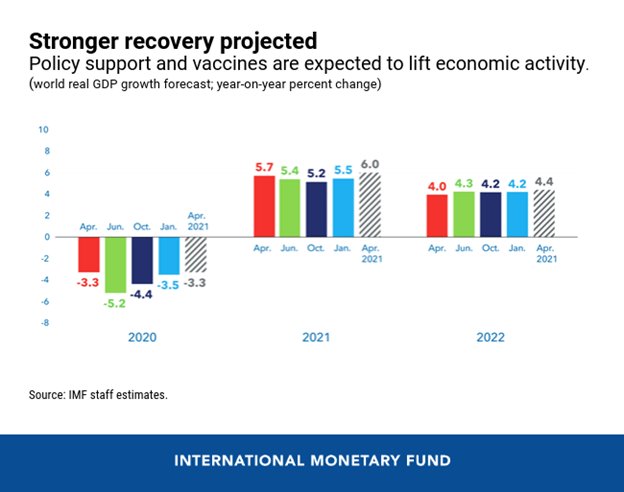

The IMF foresees a strong economic recovery. The assumption is that the virus can be controlled to such an extent that lockdowns and social distancing are no longer necessary. This is mainly due to the vaccination campaigns.

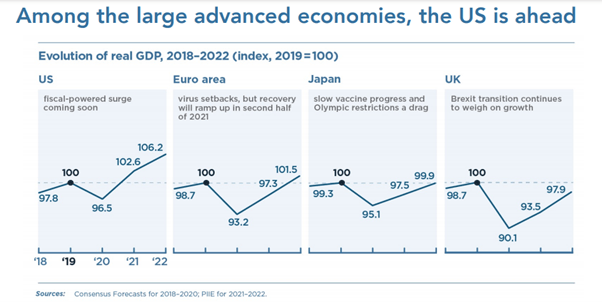

It looks like an upswing, at least in the G7 countries, this year will mean most major economies, at least the advanced countries, are likely to (more or less) reach the real GDP level of the end of 2019 by the end of this year. Europe is forecast to lag slightly behind, while the US is developing more strongly. However, the situation in the so-called Global South, or ‘emerging economies’, is different. India and other countries are in a terrible situation.

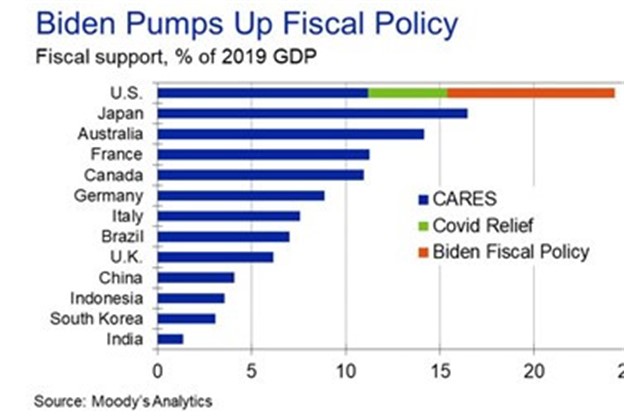

The US, along with China, is one of the countries that seems to be recovering most quickly. That’s partly because of the Biden administration’s big fiscal packages, which have reduced income losses and provided money to companies. The big question, however, is how effective and sustainable this will be.

If the IMF now says that we will have strong growth, it is mainly due to economies opening up. If a substantial part of an economy has been closed and can now reopen, there will obviously be a strong bounce back. But this pace will not be sustainable. It is really like a sugar rush and as you know, once the sugar is consumed, you feel a little sleepy and down afterwards.

The Biden administration is passing a huge infrastructure program through the US Congress to boost the economy and create jobs. Two trillion dollars sounds like a lot of money at first glance, but if you spread it over five to ten years, the stimulus then amounts to just half a percent of US economic output each year.

So Biden’s package will give the US economy an early rush, but it’s not enough to boost long-term growth. The low pre-pandemic growth rate will resume; and with it, productivity-boosting investment will be weak, wages will not grow much and jobs will remain precarious for a large part of wage-earners.

The scarring

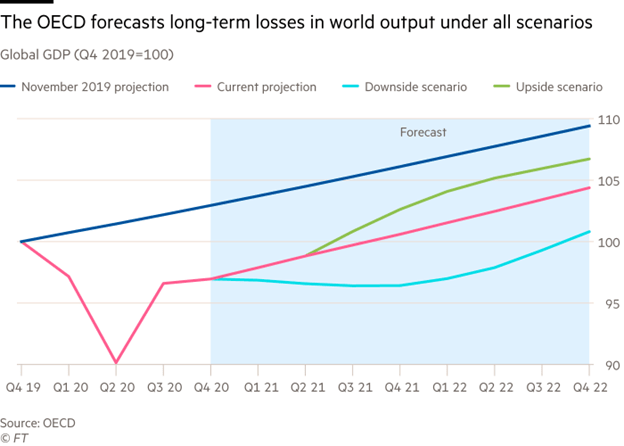

The pandemic slump has been over two years in which there have been huge losses in production, resources, income and jobs, many gone forever. Globally, the slump has pushed some 150 million people further into the most abject poverty, who were otherwise seeing some improvement. These two years have been a huge disaster. The loss of the two years will never be made up again. It’s like an abyss, down one side and up the other, but the abyss is still left behind.

Profitability and growth

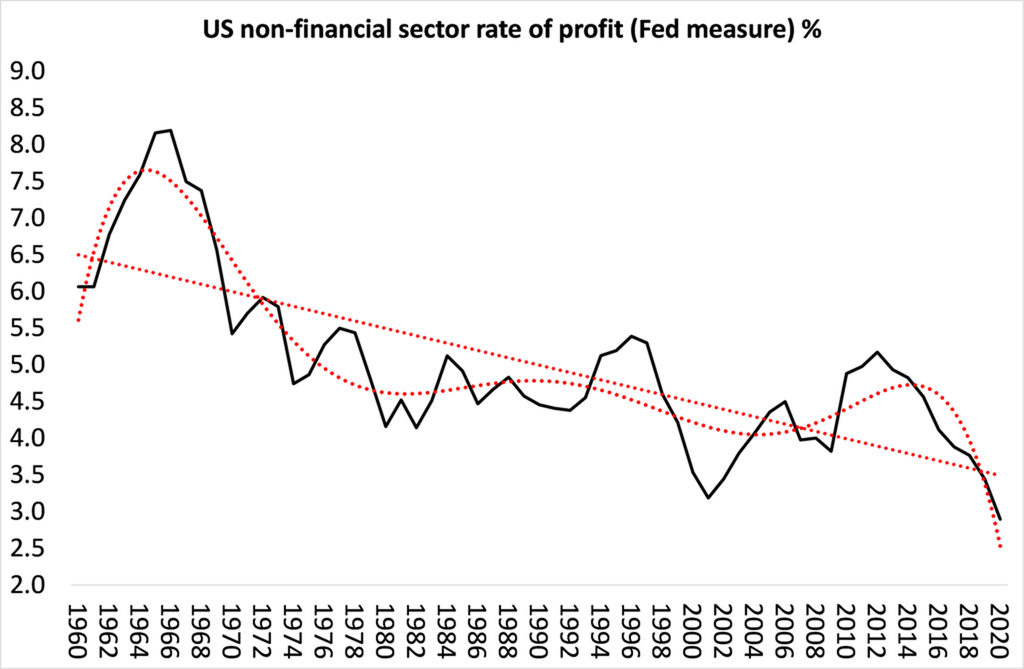

The global economy was already growing very weakly in 2019, which is likely to be the case again after the rapid recovery in 2021. That’s because capitalism grows sustainably and strongly only if profitability increases. However, average profitability was already very low before the pandemic, and in some countries, it was at the lowest level since the end of the Second World War.

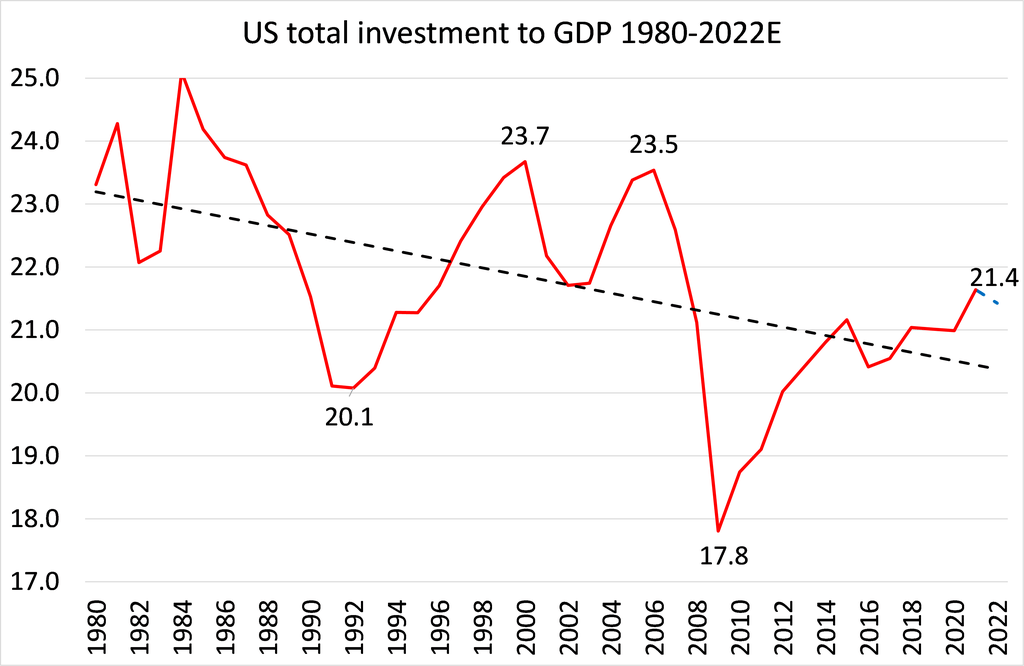

The investments now being made to boost employment and income will not restore this profitability. Profitability will improve compared to the bottom of the pandemic, but it will not go above the rates of previous years. That means that investment and growth will not improve in the longer term. In capitalism, profitability determines economic development. Investments must pay off accordingly. If we had a different economy, we wouldn’t have to worry about that.

At the moment, we see that around 15 percent of GDP is productively invested by the capitalist sector, ie not in property (4-5%) and financial speculation. By contrast, public investment is low: it contributes just 3 percent of GDP a year to productive investment, and Biden’s packages will increase that by only 0.5 percent, as above.

This will not be decisive for economic development over the long term. Indeed, even the U.S. Congressional Budget Office expects long-term average real GDP growth of only 1.8 percent per year in the US for the rest of this decade, based on its forecasts of productivity and employment growth. That rate is even lower than in the last decade.

Zombie companies and debt

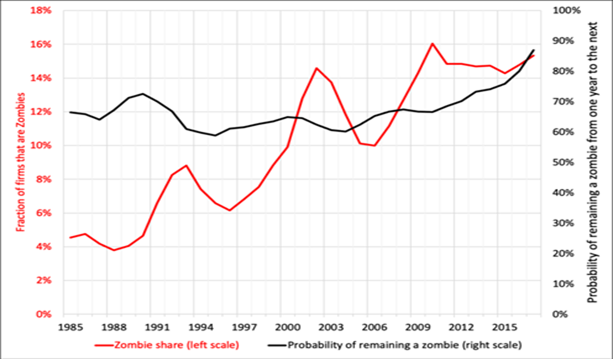

Profitability would only increase if some rotten layers of capital were removed. There are, for example, the so-called zombie companies, which make little profit and can only just cover their debts. In the advanced economies, we are now talking about 15 to 20 percent of the companies that are struggling in this situation. These companies keep overall productivity low, hindering the more efficient parts of the economy from expanding and growing.

The zombies reflect the enormous increase in debt, especially in corporate debt, globally. Debt levels are the highest since World War II in most developed economies. Interest rates are at historic lows, but the sheer mass of debt is still weighing on firms’ ability to invest productively.

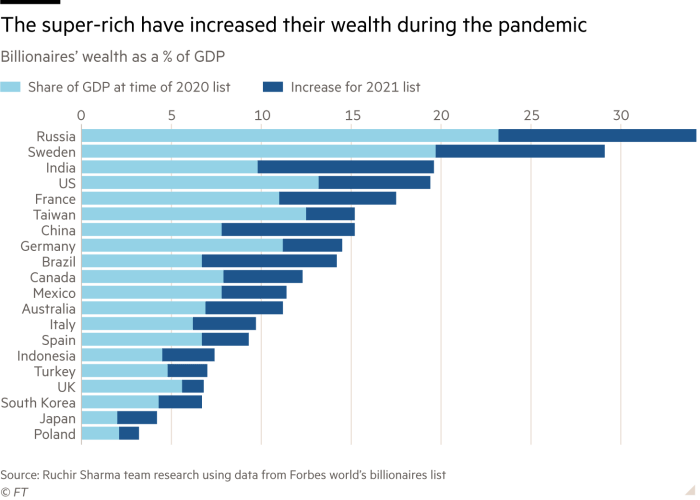

The immense debt also gnaws at profitability. When profitability falls in the productive sector, capital flees into financial speculation to make more profits. In the COVID slump, the super-rich have done so well!

When there is a financial crisis, there are defaults and devaluations, but there is no economic downturn if the productive sector is healthy. But the financial crisis can trigger a production crisis if it is combined with low profitability in the productive sector, as we saw in 2008.

Creative destruction

The burden of debt and low profitability can be overcome through so-called “creative destruction”, as Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called it. This is also the perspective of Marxian economic criticism, which Schumpeter had read very carefully. Through the devaluation (writing off) of capital and, in particular, the liquidation of inefficient, indebted companies, profitability can be raised. But that means a huge devaluation, in order to create the conditions for a new upswing.

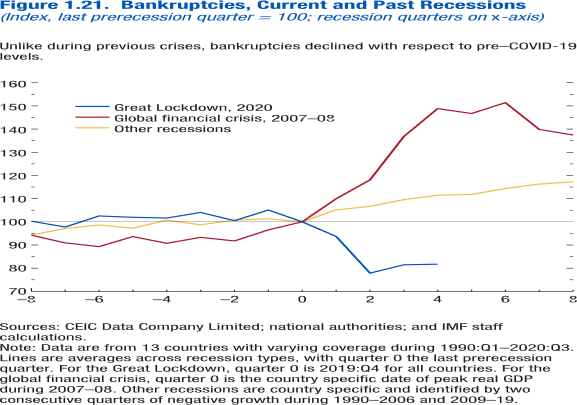

So far, there has not yet been much destruction of capital because it is a grisly thought for governments and decision-makers – instead, bankruptcies of weak firms have been very low. Governments fear the political consequences and so are forced to continue with the big credit/money glut to keep companies running even if their productivity and profitability growth slows.

Inflation

Many people have suffered severe hardship in the pandemic slump, but others have also saved money that could now be spent as economies open up. This will lead to a sharp increase in demand for all kinds of goods and services. Probably the supply side will not be able to keep up with that. So there could be stronger inflation over the next six to 12 months, especially in import prices, as international supply chains are still weakened. We could therefore see a rise in prices over a period of time.

Inflation in the late 1980s was immense. In most advanced countries, it was in the double-digit percentage range. Over the last two decades, inflation in these countries has, broadly speaking, been around 2%. But perhaps we will see inflation for the next 12 months until production can catch up with increased demand.

The monetarist theory that an increased money supply must lead to inflation has been proven wrong. Central banks have spent vast amounts of money and supported banks and firms without prices rising. While the sum of money has increased, its orbital speed has decreased. Instead, it was parked at the banks, which did not lend it onto companies. The big firms often did not need the money, the smaller ones were cautious about borrowing even at low interest rates. So the banks put the money into financial speculation. There was also an unprecedented rise in the price of financial assets. But will it continue?

The answer is complex, but there are certainly two factors that are decisive. On the one hand, how much value is present in economies, how much flows to the capitalists as profit, and how much goes in wages to the workers. The development of these variables determines demand. The capitalists drive the demand for capital goods, the wage-earners for consumer goods. The level of wages and profits is therefore central, but the supply of money also plays a major role, because this is intended to compensate for weak profits and thus to stimulate demand.

In Marxist theory, there is a strong argument for a long-term decline in inflation. Rising productivity means that less investment is made in labour power and more in means of production, which also leads to an increasing organic composition of capital. As a result, both sources of demand are undermined: wages and profits (new value) growth slows. Capitalism therefore has a tendency towards disinflation when there are no counter-measures involved. Central banks have been trying to reverse the disinflation trend with money injections for about 30 years, but with little success.

The Keynesian notion that higher wages drive inflation is not supported by the evidence. Marx had once conducted a discussion with Thomas Weston, a trade union socialist of the Ricardian school. Weston claimed that the fight for higher wages must also lead to higher prices. Marx replied that this did not have to be the case, since the higher wages would likely come at the expense of profits. Inflation only needs to occur when wages and profits rise at the same time and then demand increases, while investment remains relatively low due to low profitability. It depends on the combination of these factors.

Golden Years and neoliberalism

The golden years of post-World War II capitalism were an exception, at least for the advanced economies: near full employment, rising living standards, high profits in advanced economies, and expansion of trade. If you look at the history of capitalism, you don’t find many such periods. The closest is probably the “Belle Époque” from the 1890s to the 1910s. The big question is: why didn’t these phases last?

Neither mainstream economists nor most left-wing theorists have an answer to this question. The latter claim that the post-World War II phase was over because of the departure from Keynesianism – because governments stopped spending enough money and stopped managing the economy. The follow-up question arises: why did they stop? The answer is found in economic development itself, the declining profitability of large capitals. This led to a decline in investment, to which Keynesian macro management did not find an answer. Thus the big capitals put pressure on governments to take a neoliberal path.

The law of value and profit

The central argument of Marxian criticism is based on the law of value. This roughly means that companies only invest if they can make a profit. Profit is the centre of their actions and not the needs of the people. These are only considered important so that the products can be purchased. Profit, however, comes from the exploitation of the labour force in the production process. Labour produces goods and services that can be sold but in constant competition with other capitalists. This means that companies are constantly looking for better methods of exploitation, new technologies and new methods.

For mainstream economists, profit simply does not matter. But even among the left-wing Keynesians, profit hardly appears. For them it is all about ‘demand’, about ‘speculation’ or about ‘financialisation’. These things all play a major role, but profit is the key category for understanding the capitalist process of production and accumulation. And it is important to put it in relation to a company’s investments: the rate of profit is the key to understanding how healthy an economy is. And profitability has tended to fall over the last 50 years, not linearly, but in a wave-like movement.

The high profits of tech companies such as Amazon, Apple or Alphabet are hiding the problem of profitability across the whole capitalist economy. There are a lot of unprofitable zombie companies and for most profit rates have fallen. We need to look at how this has affected investment. This is the central aspect that Marxian economic criticism can bring to the debate on the world economy.

Empirical evidence supports Marx’s law of the tendency to fall in the rate of profit. There are the counteracting factors to this law, but the law is the dominant factor. As far as we can measure the data, they suggest that there is a long-term trend towards falling rates of profit in the major economies. Every eight to ten years, capitalism plunges into crisis. We must continue to learn why these crises take place and what the political consequences are.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.