By Harry Hutchinson, Labour Party member, Northern Ireland .

This period marks the centenary of the partition of Ireland, the establishment of the separate state in the North and the ‘treaty’ state in the South, the latter eventually becoming the Irish Republic.

A hundred years after these events, the National Question remains the unsolved fundamental issue facing the people of this island. North and South, politics has been dominated through generations by parties that have maintained divisions on this question, and they will continue to do so for as long as the question remains unresolved. It was the creation of the border in 1921 that has since divided politics more than anything else.

This division is the product of attempts to resolve the National question from an imposed capitalist perspective, something that has not and will never be the basis of a solution of the issue. Driving British Imperialism from the 26 Southern counties was indeed a major advance, removing British landlordism from rural and urban areas. But this came at great cost in Irish lives, in both the War of Independence before the 1921 Treaty, and in the Civil War that followed it, between pro- and anti-Treaty forces in the South.

“…your efforts will be in vain”

If anything is to be learned from events a hundred years ago, it is that imposing a solution on the ‘Irish problem’ from a British or even an Irish capitalist perspective is usually dealt at the end of a gun, and in fact it doesn’t resolve anything for the majority of the people of Ireland as a whole.

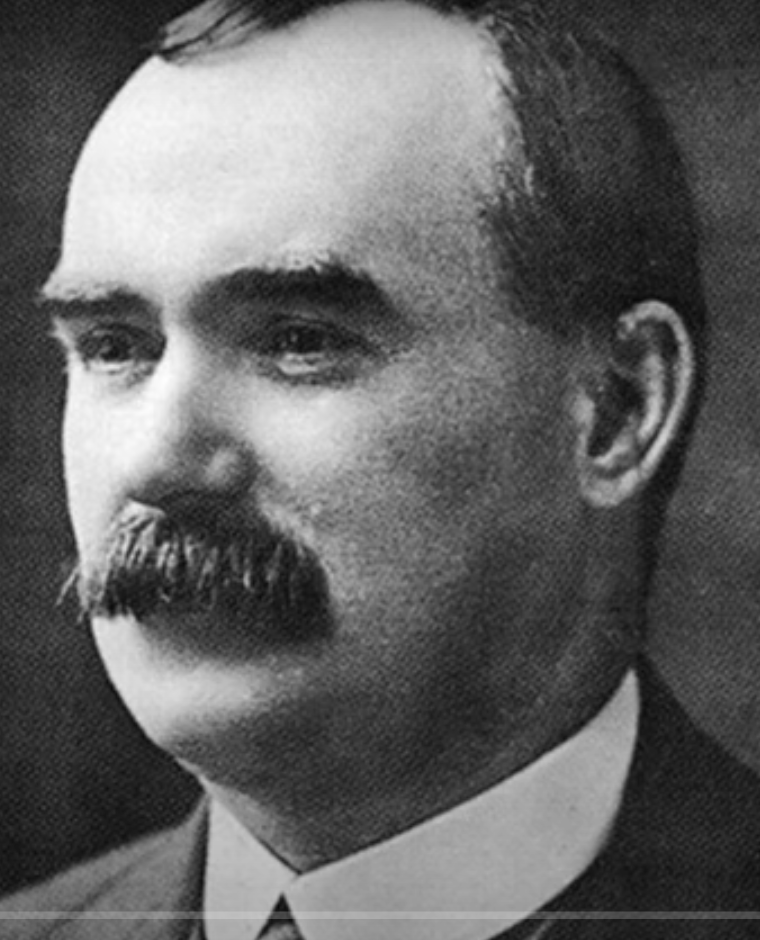

As James Connolly once said, “if you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of a socialist Republic your efforts will be in vain. England will still rule over you.” Much has changed since Connolly’s era, in relation to capitalism internationally, particularly the utter collapse of Britain’s power and prestige on the world stage in the last hundred years. Nevertheless, Connolly’s words still resonate today, in the sense that in any approach to the Irish national question, the essential requirement is a socialist agenda, to empower the overwhelming majority of people – the working class – to own and control the means of production, distribution and exchange, and thereby to properly determine their own destiny.

Partition between the North and South, and within the Northern state, between Catholics and Protestants, was a deliberate act by British Imperialism. It was a means of maintaining a ‘divide and rule’ policy, principally by means of the different religious and culture traditions in the North, to check the movement of the working class at that period.

Calls for a capitalist united Ireland

To the detriment of the people of the whole of Ireland, partition has dominated the political scene for the last century. Capitalist Unionist and Nationalist parties have dominated the Northern state for decades and in the South, Treaty and non-Treaty parties. Sinn Fein emerged as an all-Ireland political movement calling for a (capitalist) united Ireland. The terms still set today by Sinn Fein for a united Ireland remain based on capitalism, despite nods in the direction of ‘radical’ reforms, and they risk further division and at least the potential of renewed civil conflict.

After partition, discrimination against Catholics in the North in terms of jobs, housing and education were continued throughout the whole period of Unionist Government. Gerrymandering of boundaries ensured that Catholic majority cities like Derry remained in Loyalist hands and there were voting restrictions that limited Catholic votes and boosted Protestant votes.

Likewise in the South, the ethnic cleaning of Protestants continued throughout the century. Arson, intimidation and looting drove over 10,000 out of Dublin alone in the early 20s. Attacks on Protestants took place in 19 of the 26 counties in Ireland. Even in the recent centenary of the Easter Rising, in 2016, Protestant churches were forced to close.

Any attempts for a solution left to the capitalist and sectarian parties is doomed to failure, as is any from a British and/or Irish government intervention. None of these parties have the political capacity to bring workers together in a way that would resolve the problem of partition. On the contrary, there is a danger that the Northern state, which is more divided than at any time in its history, could degenerate into further violent conflict, leading to further ethnic cleansing from Protestant and Catholic enclaves.

Intelligence gathering during the Troubles.

One of the main objectives pursued by the British throughout all of the period of the Troubles was intelligence-gathering. It is estimated within one year of the Thatcher Government coming into office, there were hundreds of Republican informers working for the British state. By 2002, when the IRA broke into Castlereagh Barracks and stole documents listing informers, one senior security officer claimed there were so many that the IRA were unable to act on their findings. Effectively, for them the ‘war’ was over.

Republican, Loyalist and British sources have claimed there was hardly one terrorist incident that the British security services did not know about in advance. British security either turned a blind eye or directly instigated killings, largely though the notorious Glenanne Gang, made up of British security personnel and Loyalist paramilitaries. The brutal gunning down of innocent civilians within a five-month period in Ballymurphy and then Bloody Sunday by paratroopers is today recognised as an International war crime.

Atrocities throughout the Troubles, like the 1974 Dublin/Monaghan bombings, which killed 34 people, to the 1998 Omagh bomb, the single largest loss of life in one incident, killing 29 people, were known in advance by British intelligence. Nothing was initiated to prevent these attacks, which included sacrificing RUC officers, to protect the identities of informers. Intelligence-gathering took precedent over people’s lives.

Ruthless repression used by British Army

The families of victims seeking justice have been frustrated by the British. Half a century later, some inquiries have taken place, like the Bloody Sunday and Ballymurphy Inquiries, and they have exposed the ruthless repression used by the British in Northern Ireland. Of the number of inquiries by the Historical Investigations Unit, almost all have pointed to British security involvement. Yet only one British solder is facing trial for his crimes.

For the Britain to allow genuine and open inquiries into terrorist incidents during the Troubles, it would expose the role of MI5 and other security establishments. Terrorist incidents led to over 3,500 deaths. It remains one of the highest numbers in any conflict zone in the world and Britain cared nothing for the deaths.

The flaws in the Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement heralded a new era in Northern Irish politics, and it was supported overwhelmingly in both the North and the South, as a welcome ‘new dawn’ after 30 years of troubles. Workers both Catholic and Protestant were tired of the senseless sectarian deaths on both sides.

However, the Good Friday Agreement was founded effectively on the institutionalisation of sectarian parties. The Unionist and Nationalist Parties had no intention of bringing the people of the North together. On the contrary, they have used every opportunity to maintain the divide between working people to maintain their electoral base. The divisions can be seen in the increase in the number of so called ‘peace walls’, which are more like ‘division walls’ at the interfaces between Protestant and Catholic communities.

After the GFA and the reopening of Stormont, the two main Parties, the DUP and Sinn Fein, formed a coalition, their cosy power-sharing arrangement isolating all other political parties. Unlike in the past, Sinn Fein are no longer able to act as a opposition to cuts in public services, and alongside the DUP, they have supported ruthless cuts in spending on hospitals, schools and other services. They have essentially abandoned the most vulnerable by handing over benefit reform to Westminster, with resulting hardship to many and tens of thousands of premature deaths.

Any illusions that a new all-Ireland agenda can be based on these neo-liberal sectarian parties or on building something on the Good Friday Agreement must be dispelled.

Labour and the trade unions.

The first Irish Labour Party, formed by Connolly, Larkin and O’Brien in 1912, was an all-Ireland Labour Party. Partition cut across this and it resulted in a reactionary “Unionist” Northern Irish Labour Party and an Irish Labour Party in the South that abandoned both the North and, since the 1950s, any pretence of working-class struggle in the South.

The NILP actively supported the Northern state remaining part of the UK. In the 1973 border poll, it urged people to vote to remain in the UK. This position split the party and its Catholic members left en masse. In the same year, the NILP even supported a strike called by the Ulster Workers Council that effectively brought down a Stormont government. It brought the Northern state to a standstill, although it was largely by roadblocks and intimidation, rather than by democratic work-place mass meetings or trade union votes. The NILP at that time, despite a momentary shift to the left, was soon supporting a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people.

The NILP effectively wound up and the newly-formed SDLP – although largely a Catholic party – is looked upon by the British Labour Party as its ‘sister’ party. In the South, the participation of Labour in successive capitalist coalitions has reduced the party to a machine for the furtherance of a handful of parliamentary careers. It has not a single trade union affiliated to it today.

Neither of these two parties, therefore, is in any position to advance the struggle to defend the living standards and interests of the working class in Ireland, or to take up the challenge of the National and border questions.

Many missed opportunities

At different periods in the last century, there have been opportunities presented to both Labour Parties to unite workers around a struggle for change. In the run up to partition and after the involvement of the Irish Citizens Army in the Easter Rising, and subsequently the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, Labour emerged as a potential major force in Ireland, including in the more industrialised North.

With partition looming, the Irish Labour Party leadership unfortunately failed to intervene and to appeal for unity between Northern Protestants and Catholics, as they could have done, on the basis that a British-engineered Parliament had nothing to offer them. They were being offered rule by a reactionary capitalist Unionist government that would offer them at best meagre advantages over Catholic workers.

Just as important, Irish Labour failed to struggle for an alternative to a capitalist Home-Rule, all-Ireland state, leaving the scene to be dominated by Sinn Fein. Their policy offered nothing to change Irish society, only a state dominated by the Church. This was in the context of a wave of workers’ struggles and revolution sweeping Europe in the wake of the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Sinn Fein given a free run in 1918

Instead of an independent class programme, the Irish Labour Party even stood to one side and allowed Sinn Fein a free run to win a landslide in the 1918 all-Ireland election, an event that opened up the perspective of a Catholic Church-dominated all-Ireland state, in the eyes of the Protestant North.

Decades later in the late 1960s, we had the Civil Rights movement and the Battle of the Bogside in Derry. Although the CR movement was predominately Catholic, it had passive support among important sections of the Protestant working class and particularly among the youth. Again, the Northern Ireland Labour Party and the Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions failed to intervene and unite workers – as they could have done, linking civil rights to the issues of low pay, housing, unemployment, education, and so on.

That left the Civil Rights movement to be taken over by largely Catholic nationalists and Church figures and then to be brutally crushed by the British state. Events that followed, like internment, the massacres in Ballymurphy and Bloody Sunday were the inevitable consequences of the suppression of the Civil Rights movement two years earlier.

There have been crucial opportunities, therefore, for the Labour and Trade Union movement to intervene and change the course of Irish history, but such opportunities have not been taken.

Workers’ unity persists in the workplace.

A key question facing the labour movement today is the campaign for a border poll. A significant head of steam has been built up by the Trade Unionists for a New United Ireland, which, although it appeals for workers’ unity in words, is in fact entirely based on the notion of a capitalist united Ireland. As it was in 1918, it is a case of first unification, and only then socialism.

The central question facing socialists today is exactly as it was a hundred years ago. Any campaign for a new Ireland can only be based on workers’ unity between Protestant and Catholics in the North and between workers North and South. This is not an incidental extra; it is the essential element of any resolution of the National Question.

The main organisation of the working class is the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, which represents over 800,000 workers across the whole of the island. The Northern Ireland Committee of the ICTU represents over 200,000.

These trade unions, their leaders and their tens of thousands of shop-stewards, reps and branch officials have a vital role to play in the struggle for unity that is the essential foundation for any development towards a genuine new Ireland. It remains the case today, despite the sectarian divisions in the North in terms of housing, that most large workplaces, particularly in the public sector, are fully integrated. This essential integration of the workplace could be a foundation on which a mighty new unified workers’ movement could be built.

Bread and butter issues, not constitutional issues are key

It would be a movement that focused not on ‘constitutional’ issues or the border per se, but on the issues of low pay, job insecurity, unemployment, health, education, welfare, housing provision and all the necessities of working-class life. It would raise the issue of socialist demands and socialist change to put into effect measures in the interests of working -lass people. The only way that a ‘new Ireland’ can be brought about in a way that respects all religious and cultural rights, along with human, civil and sexual rights, is on the basis of such a campaign for socialist change.

Across the whole of Ireland, including in the South, there are many community-based campaigns and struggles. There are environmental campaign groups, like the anti-mining movement. There have been huge campaigns in the South against the imposition of water rates, and there have also been very successful campaigns on women’s rights, on abortion, divorce and for marriage equality and reproductive rights. All of these have been supported by the trade unions and overwhelmingly by young workers. All of these campaigns can play a part in shaping a new Ireland.

An all-Ireland Labour Party.

What is missing is a political voice to challenge the parties of capitalism and the status quo and to take up the National question on the basis of a unified front and bring people together with a socialist agenda to create a new Ireland. Ireland needs a new political voice, based on the Irish Congress of Trade Unions and for the whole of the Island of Ireland.

What is absolutely essential now is bringing together all the community campaigns, environmental campaigns and especially the trade union movement in a new all-Ireland party of labour.

Build confidence and trust among Protestants and Catholics

A new Ireland Labour Party would need to deal with the Irish question from the standpoint of the day-to-day needs of workers, with social questions at the core of its programme: homes, pay, employment, investment, democratic state/community control of education and health services, and so on. Only on that basis would it be possible to build confidence and trust among Protestant and Catholic workers in the North. Uniting workers around a socialist agenda would be the main priority of an all-Ireland Labour Party, not just a thin veneer to hide a sectarian head count.

More than anything, a new Irish Labour Party would have to rest on the solid foundation of the trade union movement. It could provide a basis for building strong links with the labour movements in Scotland, England and Wales and with the trade union movement in Europe.

An-Ireland Labour Party could be a voice for working people in the whole of the island of Ireland. It could form the basis of a real unity among workers, instead of division. In a skilful and meaningful manner – meaningful in the sense of concrete day-to-day workers’ needs – it could bring the working class of this island together. It could be a solid foundation for a united movement to end centuries of capitalist exploitation and for a fight for a socialist united Ireland.