By Cain O’Mahony

At the beginning of the 1960s, the protracted post-war economic boom gave the illusion that capitalism had resolved all its boom-slump problems of the past, and had now reached the pinnacle of civilised development.

In the West at least, it appeared to be a time of recovery and progress, with even the poorest households seeing incomes improving. The traditional vehicle of revolutionary change – the working masses – appeared somnolent; a strong trade union movement was winning pay rises and improved conditions as the boom-time bosses had money to spare for concessions, to keep the wheels of industry rolling and the profits coming in. The working class felt it was moving forward.

Yet all was not well. The oppressed backwaters of Western society, and the former colonies too, witnessed the boom times and wondered, rightly, why there still seemed to be so few crumbs on the table left for them. For the West, with these affluent times came the television. Now, all the shocks of this epoch – Vietnam, Biafra, South Africa, the beatings of the Civil Rights marchers in the Southern US states, the assassinations of the Kennedy’s, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X – could be beamed into every home: distant injustice was no longer far, far away.

The old saying goes that when the winds of change do blow, it is the tops of the trees that are first to sway. So, it was the new breed of university students that was first shaken from their slumber.

Technological advances

Universities were fewer in number than today, and still very much the domain of privilege and elitism. They were thoroughly middle class. In France, only 6.6 per cent of students were from peasant farming backgrounds, and only 9.9 per cent from the working class. Western Germany was even worse – only 5 per cent of university students were the sons and daughters of industrial workers. Britain fared better, given its post-war education reforms. Even so, in Britain in 1968, 75 per cent of university students were still from middle or upper-class backgrounds.

Even so, they still had battles to face. The prolonged economic upsurge and the rapid growth in technological advances meant society needed an expanding, highly educated labour force to administer it. There was an explosion in higher education intake. But while society’s strategists agreed on the high numbers required, it was not matched with the resources needed to cater for it.

France was the starkest example of what was rapidly going very wrong. In 1958, France had 170,000 university students; ten years later this had risen to 514,000. Yet there were not enough facilities to service this huge growth, despite attempts to rapidly build soulless ‘red brick’ monstrosities. Successive governments then tried to keep the numbers down by pushing university degree standards so high, that by 1966 between a third and 50 percent of university students were being failed mid-term and thrown off their course, causing much resentment and anger at the shifting goal posts.

Marcuse came to their rescue

But who would fight for them? Their isolation from the masses was compounded by their bitterness that the slumbering proletariat did not share their new radical ideals. Their parents – even the middle-class ones – had faced the trials of mass unemployment, fascism and war in the 1930s and 1940s, and had little sympathy for the new ‘struggles’ of their sons and daughters. The 1960s was the decade of the ‘Generation Gap’. As Jillian Becker, in her examination of the Baader-Meinhof terror group, put it:

“But some call them the spoiled children of the economic miracle… To be privileged, free, indulged, well fed, well housed, well clothed, was to stand accused! Except that Herbert Marcuse came to their rescue…he told them they were in fact oppressed and subjugated by the very plenty and comfort and tolerance which they enjoyed” (Hitler’s Children, 1977).

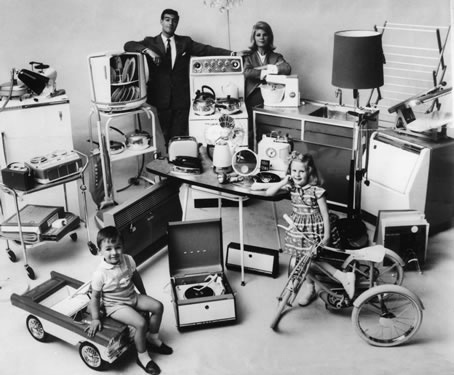

Herbert Marcuse, one of the new generation of so-called ‘Marxist’ philosophers emanating from Frankfurt, did indeed come to their rescue. His 1964 book, One-dimensional Man, proclaimed that the new ‘consumerism’ had already bought off the working class. From being the ‘ferment of social change’ as envisaged by Marx and Lenin, Marcuse joked, the working class had become the “cement of social cohesion”. They had sold out, been bought off, ‘bourgeoisified’: “The people find themselves in their commodities: they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split level home, kitchen equipment… It is a good way of life — much better than before, and as a good way of life, it militates against qualitative change.”

His comments in fact demonstrated the circles he was moving in – in the 1960s, the working class did not have all those consumer durables, which in turn shows the flaw in Marcuse’s argument: the working class did not obtain many of these consumer delights until the 1970s, yet rather than send them to sleep, this was the most explosive decade of the post war period, in terms of the class struggle and mass strike movements.

But Marcuse had tapped into the ‘reality’ of the middle-class students. The consumerism being enjoyed by their middle-class homes made them assume the whole world was like this. Therefore, they bought into Marcuse’s theory.

The politics of alienation

He also explained to the students the politics of alienation, writing: “Contemporary ideology thus ensured that the cycle of production and consumption reproduced political domination and perpetuated man’s alienation from his own potential.”

This struck a chord with the frustrated students, particularly those suffering the petty rules of an older generation. The aged academics who ruled attempted to push the rebellious youth, with their long hair, loud music and exotic fashions, into the straight jacket of conformity. The modern Nanterre university in Paris was a prime candidate for revolt with its maze of childish instructions. Students were not allowed to change the furniture in their regimented, box-like rooms. No cooking was allowed. No males could visit the female quarters (the latter being a sure-fire recipe for revolt). And all this in a climate where the authorities were looking to expel students to keep down their ever burgeoning in-take.

Marcuse showed the students that they, too, could identify with the oppressed of the world. They, too, were in a prison – a prison of consumerism and ‘illusionary’ abundance, the sole design of which was to shape them to conform, to make them into good little capitalists. They were expected to sign up to an ideology for which napalming the innocents in Vietnam was acceptable, yet they were not even allowed to procreate with the opposite sex. Marcuse’s popular slogan – ‘Make Love, Not War’ – soon became the watch-word of the 1960s.

But with the labour movement having ‘sold out’, where would the new force for change come from? Marcuse now showed them the short cut they could take to revolution, around the slumbering and stagnant masses: it was via the ‘substratum’ of the new layers of the oppressed.

Outcasts and outsiders

“Underneath the conservative popular base is the substratum of the outcasts and outsiders, the exploited and persecuted of other races and other colours, the unemployed and unemployable. They exist outside the democratic process…Thus their opposition is revolutionary even if their consciousness is not.”

For the ‘New Left’ as they began to be called, based around the ideas of the likes of Marcuse and his mentor Theodor Adorno, if the ‘bourgeoisified’ proletariat wouldn’t fight, then they now had the theoretical bridge to link up with their ‘brothers and sisters’ amongst the ‘sub-stratum’ who would. And they would do it in the here and now, and not in line with some distant perspective much beloved by old-school Marxists.

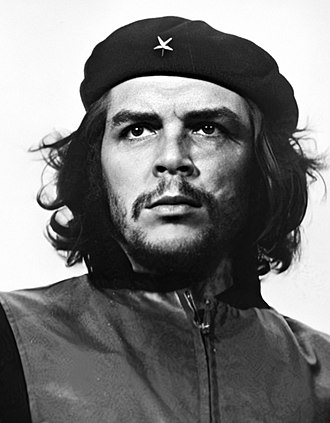

What galvanised the New Left was opposition to the Vietnam War. The victories of the Viet Cong over mighty US imperialism were ‘proof’ that Marcuse’s underdogs could lead the world revolution to victory. Likewise, the victories of Castro and Guevara in Cuba fostered further faith in guerrilla-ism and direct action. The proclamation of Che Guevara – “If you are a revolutionary, make a revolution!” – was a call to action that ensured his image adorned many a T-shirt and as well as posters in student halls of residence, to be revered and adored. And through Marcuse, their struggles in the world of academia were now inextricably linked to the anti-colonial fight being played out by the underdogs in Vietnam, Cuba or whatever cause of the day.

All these ingredients ensured a rejection of the traditional Marxist method of working through the mass organisations of the labour movement, and instead steered many towards spontaneous direct action.

Mike Gonzalez, a post-Graduate at Essex University between 1967-69, described the mood that gripped the New Left:

“Once you’ve decided that the System cannot ever allow freedom or the things you value, the debate then is, well, where do you go, how do you change it? There’s a lack of confidence in the mass movement. The belief that the trade unions can too easily be diverted into small changes and reforms rather than revolution and so on, led people to look elsewhere, and where they looked was towards the Third World, to forms of direct action that would enable change to take place in the here and now.

“And a very influential model was Cuba. What happened in Cuba was that a small determined, committed group of revolutionaries, rather than waiting for the movement to grow, acted directly themselves against the state, overthrew the state, and that therefore became the model, in other words the revolution could be the act of a few who would then in their turn spark the wider movement…the revolutionaries would act on behalf of, act instead of the masses” (interviewed on Generation Terror, BBC4 2003).

The New Left Phenomenon

The impact of these new ideas split the left. As Caute, in his analysis of the ‘New Left’ phenomenon, explained:

“The Old Left, whether revolutionary or reformist, accepted the necessity of political parties, each competing with others for control of the state. Adversarial politics inevitably involved leadership, hierarchy, discipline. The most fundamental characteristic of the New Left was its libertarian distrust of state power, parties, competition, leadership, bureaucracies and finally representative government. The New Left demanded ‘participatory democracy’ not only in the universities…but in the wider society as well. The vision, part anarchist, part Rosseauesque, was generally derided by the Old Left as both aggravatingly utopian and a free ride for charismatic orators seeking power without responsibility” (1968: Year of the Barricades, David Caute)

Perhaps one event that best personified the rift between the two sides was the establishment of the ‘Anti-University’ in the (then) working class bastion of Shoreditch, East London. Trumpeted as bringing education to the masses, in reality middle class drop-outs sat inside all day in angst-ridden arguments about personal politics; just down the road in the real world outside, building workers were in a bitter dispute with their employers at the new Barbican construction site. The Anti-University made little, if any, contact with the pickets.

In the UK, the New Left infection was affecting those who had formerly claimed to be Marxist. After World War II, the former Marxist movement split into four basic camps, all active in the Labour Party: Ted Grant’s group, which retained Marxist ideas and method, formed the Militant group in 1964, to continue the fight for socialist policies in the Labour Party. The other three groups had all been on a steady march towards opportunism and ultra-leftism.

But this march turned into a stampede as they saw (hopefully) rich pickings amongst the students, and a short cut to revolution around the mass movement. While Grant remained firm, the other three groups all now declared the Labour Party, and the wider trade union movement, as ‘bourgeoisified’ and abandoned the Labour Party in search of the New Left.

Spontaneous general strike

Their short-sightedness was on display in April 1968 at a meeting called by the ‘United Secretariat of the Fourth International’ (one of four ‘Fourth Internationals’ available, all of which were ultra-left) at Caxton Hall in London. It was addressed by the USFI’s Ernest Mandel. Mandel was challenged by the Marxists on how, as a ‘Marxist’, he could now write off the working class? Following the Marcusian theme, Mandel retorted that the western proletariat was ‘quiescent’ and that this situation would not change for another 20 years. Four weeks later came the May events in Paris; as students battled on the streets with the riot police, over 10 million workers exploded into a spontaneous general strike.

The general strike was derailed by the leadership of the French labour movement, and the French Communist Party in particular, who in the most antagonistic way were hostile to the students, and separated the workers’ struggle from the students’ fight, into one of simply wage and workplace reforms. Equally, it has to be said that the rank and file of the French workers found little attraction in the anarchic ‘auto-gestion’ or self-government attitudes of the student left.

For the Marxists around the Militant group, the general strike, albeit having failed, demonstrated that the western working class was not ‘bourgeoisified’ at all, and was still prepared to fight to change the world, if a correct leadership was given. Had the New Left approached the workers with a Marxist programme, consistently working alongside them, instead of writing them off for 20 years, the course of history could have changed in France.

For the New Left however, the failure of the French general strike convinced them that Marcuse was right after all, and the western proletariat would always be bought off with a few reforms. But it also disillusioned many, and the New Left began to run out of steam and internalise. As their sphere of influence retreated, so they split between a determined ‘direct action’ cadre and those who returned to their middle-class roots and concentrated on gradual liberal reform (and for some a comfortable career in the Labour and Social Democratic bureaucracies).

Initially the direct-action camp took it out on those philosophers who had inspired them in the first place. Now the big issue of the day for the direct actionists was ‘praxis’: that is, it was time to practice what you preached by ‘any means necessary’ to quote the old Black Panther adage.

Substitute for the masses

Like Dr Frankenstein, the Frankfurt School of new ‘Marxism’ found the monster they had created now turned on them, in those bitter days of recrimination of 1969 and 1970. The hardcore praxis cadre of the New Left begun to contemplate ‘military action’. Their impatience with the working masses not heeding their call to arms – or for that matter the ‘sub-stratum’ not changing the world – led them to substitute themselves, to act ‘on behalf of’ the masses, which would eventually lead these small diminishing groups of individuals to terrorise the world with guns and bombs, with the rise of the Red Army Faction in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, and to a lesser extent the Angry Brigade in Britain, and the Weathermen in the US.

Far from bombing any reforms out of capitalism, they gave it instead a legal excuse to impose draconian laws and measures – for later use, in many countries, against the organised labour movement – and besmirched the name of socialism by allowing the ruling class to associate terrorism with revolutionary ideas, and frighten workers away from genuine Marxism.

But the first terror was against their old teachers. Marcuse’s mentor, Theodor Adorno had to contend with being presented with red rubber teddy bears by contemptuous students.

Marcuse himself received an aggressive reception when he returned to lecture at Frankfurt University in May 1968. Before they went off to rip down the university’s emblem and set it on fire, the hardcore students mercilessly heckled Marcuse as he attempted to speak. Finally, he gave up, and as he left the stage gave a fitting curtain call on the ‘utopian’ New Left in the 1960s:

“Those who are for praxis and against theory, are nevertheless the ones who have talked most here today” (Hitler’s Children, Jillian Becker, 1977).

For the genuine Marxists however, it was time to carry on, as they had throughout, working in the mass labour movement. Ted Grant had some harsh words at the time for those who bailed out of the Labour Party in search of New Left phantom armies:

“For them it is sufficient to issue ultimatums to the working class, the trade unions, the Labour Party, the Young Socialists… to give the working class its marching orders. And when the workers and militants pass them by, they ‘take off’, denouncing all those who fight, practically, for a consistent revolutionary programme and policy based on Lenin’s principles, as centrists, scabs …

“Much has been made of the alleged tendency to ‘contemplative Marxism’, to ‘waiting on events’, etc. The task facing Marxists today is certainly not to wait on history… it is to practically prepare for history, for the great historical events. Again, not by abstract propaganda, either inside or outside the Labour Party and the trade unions, but by a conscious participation in the struggles that lie ahead.

“The real perspectives of the mass movement, as has been explained, is the inevitable growth of a left wing. It is the duty of our movement to participate and prepare for these events by positive criticism, not only of the right-wing leaders, but… the ‘lefts’ (e.g., Tribune, Cousins, etc.) … it is necessary to understand that the masses will move towards a confused left reformism and centrism in the early stages. Fully participating in this movement… our tendency will be able to gain the ears, not only of the militants, but also of thousands of leftward moving workers” (A contribution on Ultra Leftism, Ted Grant, 1966).

This was not just idle talk. In April 1969, a conference of only 40 Militant supporters in a pub in south London, felt confident enough about their ideas to pledge that they would get a new premises and press, double the number of full-time staff from two to four, and produce a fortnightly newspaper, all within the next six months. A firm foundation stone had been laid by Militant, in preparation for the explosive two decades ahead. Indeed, ten years later, very few, whether shop steward or student, would have heard of Herbert Marcuse, but everyone had now heard of the Militant Tendency.