By Gray Allan, member of Falkirk CLP

In approaching the National Question, socialists need be familiar with the origins, development, and trajectory of the main political representation of nationalism in Scotland, the Scottish National Party.

The SNP have been a serious electoral force in Scotland as long ago as the nineteen seventies, but little attention was paid to this by the media, until, that is, the Salmond majority SNP government was elected in 2011 and again following the 2014 Referendum on independence. That got attention – but only until ‘No’ won, when it went on the back-burner again.

Today, nationalism is back with a vengeance, fuelled by further Tory victories at Westminster, despite Scottish votes, and stiffened by Brexit and Scotland’s reluctant removal from the EU. With a new Scottish Government elected on May 6 and a combined SNP/Green mandate for a second referendum, IndyRef2, the world’s media are now camped out in Edinburgh. So, what then is the history of political Scottish nationalism and where is it going?

A long history as an independent state

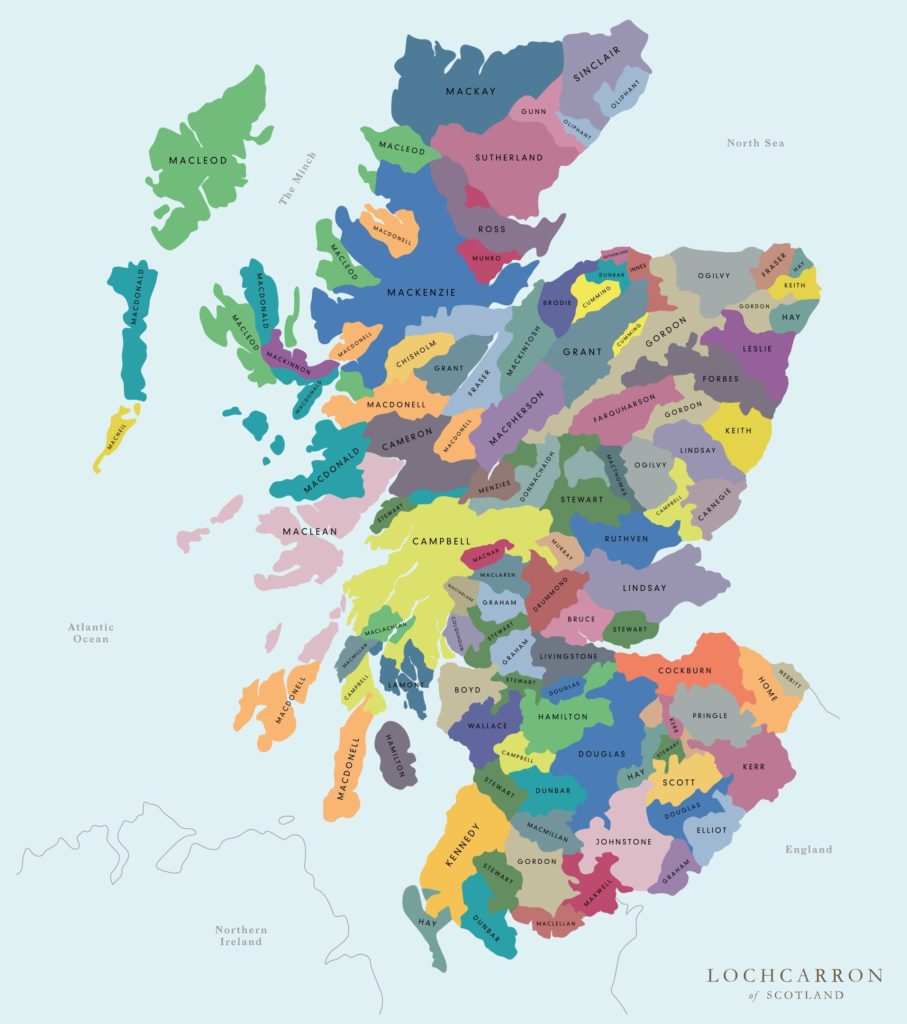

Scotland had a long history as a unified and independent state. It was itself created by the unification of smaller independent kingdoms, just as England was. Scotland had a turbulent history during the period of its independence. A predominantly Celtic, clan-based society then had a feudal system superimposed in the years following 1066, but mainly in the Lowland, more developed areas. This was introduced by Anglo-Norman settlers and then adopted by the Crown as an effective way of controlling some of the clan chiefs.

Control of the whole kingdom from the Scottish capital was always difficult, due to the geography of the country.

Large parts of the Highlands and Islands were in effect semi-autonomous fiefdoms, controlled by powerful regionally-based clans. Prominent among these were the MacDonalds, Campbells and Frasers. Scotland was not a homogenous state.

There were large cultural differences between the Lowlands and the Highlands, with Highlanders being widely regarded as ‘foreign’. Scots Gaelic, spoken latterly primarily in the Highlands, was called Erse or Irish by Lowlanders, who regarded the Highlander with some fear as backward and violent, and to them at that time, even worse, they were mainly Catholic.

This did not change until modern times, with large movements of population from the Highlands to the industrial cities, pulled in by the Industrial Revolution and pushed by the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellions, the Agrarian Revolution and the clearances of the nineteenth century,

Wars, civil strife and rebellions

There were numerous civil wars fought over succession to the Scottish Throne and over the imposition of central control. The Reformation took legal effect in 1560, but that did not end conflict over religion. Wars, large and small, between Scotland and its much larger southern neighbour took place, most notably the Scottish Wars of Independence following Edward I’s imposition of direct rule.

Scottish independence and recognition of it as a sovereign state followed the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, Pope John XXII’s support, and legal recognition by the English Crown. Apart from a period under Cromwell, who abolished the Scottish parliament and occupied the country with the New Model Army, Scotland remained independent until the union of the two parliaments, in 1707 with the Treaty of Union. This was in theory, at least, a voluntary arrangement entered into by equal parties and today this point is raised ad nauseam by nationalists.

After the Union, trade tariffs with England were abolished and trade boomed, especially with colonial America. Glasgow became the tobacco capital of the world, and was involved in the slave trade, which was intertwined with the cultivation of tobacco. The wealth of the lowland Scottish merchant class grew exponentially, further widening the chasm between Lowlands and Highlands.

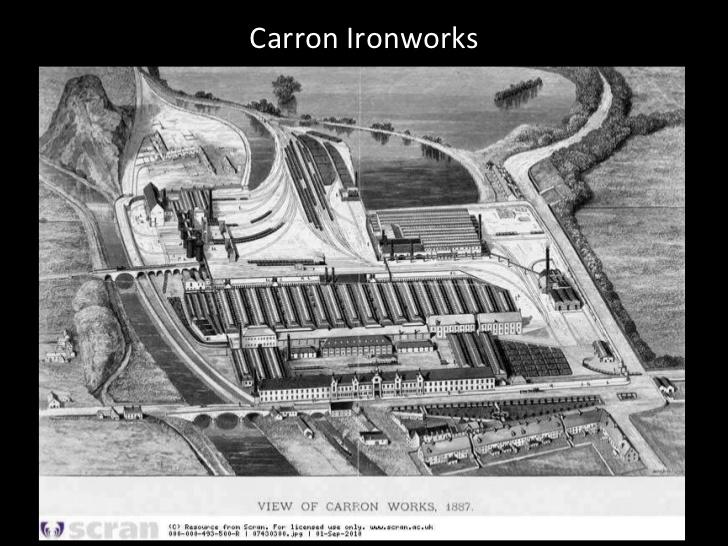

Following the Jacobite rebellions, historians noted that there was an entirely new level of participation by Scots in political life in the UK and abroad. Scotland, or more precisely the Lowlands, were central to the British economy. Carron Ironworks at Falkirk, founded in 1759, is regarded as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. The chiefs of the Highland clans slowly gave up their patriarchal role and regarded themselves more and more as landowners and capitalist investors.

This history, romanticised and mythologised, has provided and continues to provide a fertile breeding ground for the ideas of Scottish nationalism. It has featured in the Wars of Independence; it was an element in the Porteous Riot of 1736 in Edinburgh, and when Charles Edward Stuart announced the dissolution of the Treaty of Union in Edinburgh, during the ‘45 Rebellion, he was cheered to the rafters. However, when asked to join up to fight, his Edinburgh supporters disappeared like snow off a dyke!

It is, however, dangerous to interpret historical events from a modern standpoint. Political nationalism, as we understand it, did not exist until the later part of the nineteenth century. In the medieval, renaissance periods and later, a state was the property of the Crown and one’s relationship to the state was defined by land ownership. Even as late as 1793, Scotland’s leading judge, Robert McQueen, Lord Braxfield, could say, during the trial of Thomas Muir of Huntershill, “In this country the Government is made up of the landed interest, which has alone the right to be represented. As for the rabble, who have nothing but private property, what hold has the nation of them?”

Birth of the SNP and early electoral success

The modern expression of the Scottish demand for self-government lies mainly through the Scottish National Party. From its founding in 1934, up to the early 1970s the SNP was a strange sort of organisation, encompassing romantics folklorists and the like. The Duke of Montrose was its first president, along with RB Cunninghame Graham, the “Marxist Gaucho”. It attempted to be apolitical and draw in supporters of independence from left and right. It was a merger of the National Party of Scotland, a centre-left party, and the Scottish (Self-Government) Party, which was a split from the Unionist party, who supported a dominion Scottish parliament within the British Empire.

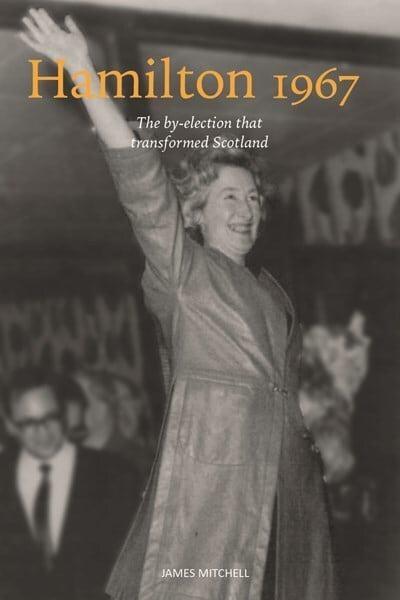

The SNP had some electoral success and won control of a few local councils. There was the occasional by-election victory, such as in Hamilton 1967, won by Winnie Ewing and then Margo MacDonald in Govan, in 1973. But at this time the SNP was strongest in the rural areas of Scotland. By 1974, they had reached a total of 11 MPs and they would not exceed that number until 2015. In 1979, they voted with the Tories to bring down the Callaghan Labour Government, ushering in the era of Margaret Thatcher. They voted against Labour over the abortive devolution referendum and claimed that they had no idea that their vote would have the consequences it did. At the following general election, they were reduced to only two MPs.

The Scottish Unionist Association was an independent Scottish party. Its merger with the Tories, identified with the London ruling class, drove some of its supporters into the arms of the Labour Party, which, while also seen as London-based, was at least seen as opposing the London aristocracy. Paradoxically some former Unionists then joined the SNP on the grounds that it was a separate Scottish party. The label “Tartan Tory” has a basis in fact, and also a long pedigree.

The 1980s saw a period of factional in-fighting within the SNP, with the expulsion of the right-wing Siol nan Gaidheal (Seed of the Gael), which has been described as proto-fascist ethnic nationalist sect. On the left, Alec Salmond, Kenny Mackaskill, Jim Sillars and others formed the ‘79-Group’, with the aim of moving the SNP to the left, with the aim of attracting Labour supporters from among the working class in Central Scotland. They too were expelled, but later re-admitted. They ultimately succeeded pushing the SNP in that direction. This does not mean that the SNP became a socialist party, far from it. But it certainly put them to the left of those right wingers at the head of Scottish Labour. The SNP constitution now even describes the party as being social democratic.

SNP moves to supplant Labour

Before the SNP could make serious headway, their first goal was to defeat Labour politically because Labour had taken most of the working-class votes in Central Scotland since the early sixties. Before that time, the class vote had been split on sectarian lines. The bulk of the Protestant working class had voted Unionist (The Scottish Unionist Association), which merged with the Tories in 1965, to become the Conservative and Unionist Party. The union referred to in the name was the union of Ireland with the UK in 1801, not the union between Scotland and England. In the 1955 General Election the Unionists still won 36 out of the 71 Westminster seats in Scotland, with a clear majority, just over 50%, of the popular vote.

The Scottish Unionists did not fight local council elections, where their members called themselves ‘Progressives’, which was basically a loose anti-Labour electoral pact. Until its eclipse, the Liberal Party also had some historical working-class support in Scotland.

The anti-Westminster rhetoric of the SNP today is fierce. It always has been, but it is getting sharper. For ‘Westminster’ read ‘England’. The overt nationalism of the SNP is purported to be a ‘civic’ nationalism, that is to say, a nationalism that is not about identity but more about fairness of administration and the nature of the democratic structures. However, this only extends to the leadership and many in the ranks of SNP supporters and members are as committed to blood and soil nationalism as any other nationalist movement in Europe.

Scottish Labour – no answer to capitalist crisis

Contrary to a commonly held view, the Scottish Labour Party was not built on the traditions of Red Clydeside. Most of the working class outside Glasgow was socially conservative and Labour reflected this. It was managerialist; in other words, it believed that as the Labour Party was “the peoples’ Party”, then once in power, then the people were in power, and socialism had been achieved.

All that was needed then was to run things efficiently. But this the Labour Party managed with only patchy success. Sections of the Party in local government also, unfortunately, became mired in sleaze and corruption. Notorious examples were the Glasgow City ALMOs (‘arms-length external organisations’) and the colour-coded application forms used in Monklands District Council. In the latter case, it was alleged that two different colours of job-applications forms were used, to indicate whether or not an applicant was known to a councillor.

However, even leaving aside these incidences of corruption – although they severely damaged the Labour Party – they had in most cases no wider vision beyond simply running councils ‘efficiently’. This meant that the Party had no answer when British capitalism entered a period crisis and public expenditure cuts. Scottish Labour councillors, complacently believing they would go on being elected year after year, simply passed on the swingeing cuts of the Thatcher government, with no more than feeble expressions of regret. This limp opposition to modern neo-liberalism opened the door for an SNP that was consciously moving to outflank the Labour Party on its left.

1997 Referendum shows clear support for Scottish devolution

Even on the issue of devolution, Labour was lukewarm. Home Rule had long been a policy of the Party, but one to which lip-service was paid, that is until the rise of nationalism forced the Party to address the issue of devolution more seriously. One of the first acts of the Blair Government was to put forward a referendum on devolution, which was held in 1997, producing a result clearly in favour of a devolved assembly with tax-raising powers

The first modern Scottish Parliament convened in May 1999. The proportional voting system used, the additional member system, was designed to ensure no party could win an overall majority and the first government, again in keeping with the tradition of right-wing Labour, was a Lib-Lab coalition lead by Donald Dewar. The intention was to encourage government by consensus.

But in the 2007 Scottish Parliamentary elections, the SNP won 47 seats, an increase of 20, with Labour losing four to the SNP and gaining 46. The Iraq War, the policy on Trident, student loans and a whole host of other measures creating a backlash against Blairism all took their toll. The SNP in 2007 formed a minority government and they have been in power since. One of their first acts was to rename the Scottish Executive as the Scottish Government, Riaghaltas na h-Alba.

The Salmond SNP Government of 2007 came to rely on the Tories to get their budgets approved, but that soon changed. The Westminster general election of 2010 was the last “normal” election as far as the Labour in Scotland was concerned. They won 41 seats to the SNP’s 6, with a swing to Labour of 2.5%, but the writing was on the wall. Once again, the Tories won a UK election, where Scotland as a whole had voted Labour.

SNP parliamentary majority and the Independence Referendum

In the 2011 Scottish government election, the SNP finally won an overall majority of seats. One of their first steps was to reach agreement with the UK Government to hold the referendum on independence, which was held in 2014, resulting in a ‘No’ majority, by 55% to 45%. The ‘Yes’ vote in that referendum amounted to 37.8% of the registered electorate.

In that independence referendum, all the most prominent Labour leaders, like Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling, Jim Murphy and others, had participated in the official ‘No’ campaign, called “Better Together”. They had done this, even though it meant sharing platforms and campaign events with leading Tories, making them indistinguishable in the eyes of working-class voters, particularly the youth, from Tories.

The results of that referendum policy had proved disastrous. It allowed the SNP to link Labour to all the Tory cuts and to set themselves up as the only defence against the Tories in Scotland. In the 2015 Westminster election, the SNP took 56 seats with almost 50% of the popular vote. Labour, still under the Westminster leadership of Ed Miliband, and the Scottish (right-wing) leadership of Jim Murphy, was almost wiped out, losing 40 of their 41 seats. The only seat Labour held was that of Ian Murray in Edinburgh South, held with the help of Tory tactical voting.

Realignment of Scottish politics for or against independence

Since that period, much of Scottish politics has realigned, in terms of Yes or No to independence. With Labour painted as “Red Tories” through participation in the Better Together campaign – a label that still clings to Labour to this day – the Party’s anti-austerity, pro public service policies, such as they were under previous leader Richard Leonard, simply have not cut through.

Today, polling consistently shows that party allegiances are linked to opinions on independence, with the (approximately) 50% in favour voting almost exclusively for the SNP. Elements of the working class have turned to the SNP as a way of “getting rid of the Tories” and for many of these workers, and even sections of the left, independence is seen as perhaps the only way to prevent the Tories ever governing Scotland again.

However, we should not overlook Scotland’s home-grown capitalist class, some of whom are salivating at the prospect of the spoils to be had in the event that the Union was dissolved! It is entirely possible for the Scottish economy to sustain an independent state. That state may well not be as prosperous as Scotland is at present within the United Kingdom, but it could certainly function. One of the worst arguments in support of the union with the UK is the portrayal of an independent Scotland as a poverty-ridden economic basket-case, or simply as being incapable of an independent country! The question is not whether Scotland could be independent but whether it should be: is independence a desirable outcome?

Scottish and English workers have much in common

The central question for Scots is this. Is England really a ‘foreign’ country? Are English people really foreigners? There are clear differences in the legal and educational systems. There are strong cultural and historic differences. There are strong differences also within Scotland, between Lowlander and Gael, Mainlander and Islander.

We share a common language with England. Less than 1% have Gaelic as their mother tongue or as a fluently-spoken second language. Somewhat more speak the Doric, the Scots dialect spoken in the North-East. For most Scots, accented English with a sprinkling of dialect vocabulary is spoken. Social attitudes, as shown by numerous surveys, are somewhat more liberal on some issues than England, but not markedly so. Racism is still to be found in Scotland and Scottish society is still blighted by religious bigotry.

To some extent, this ancient divide, based on religious identity if not actual observance, is being levered open again by the 50:50 split on the issue of independence. That bigotry had a political expression up to the 1950s, where the Scottish Unionist Association, resting on working class and Protestant votes, had a majority of the Scottish MPs.

In 1955, the membership of the Church of Scotland stood at 1.3m, or 25% of the population. It was because of the religious connotations that up to the 1970s, a Labour Party tie could be purchased in either red or green. These old splits are still to be found to some degree in the working class, especially in Central Scotland. These ideas are nowhere near as pervasive as they were, but still are linked to football club loyalties. This old sectarian divide should not be exaggerated, but it still energises a minority in the working class.

After 310 years of political and economic union, the populations of England and Scotland are more intermixed than ever before, with many family and social connections both sides of the border. The organisations of the working class, the trade unions and Labour Party are not organised on national lines but operate across the whole UK. The only exception is the EIS, the Education Institute of Scotland, which organises teachers north of the border. The problems faced by workers are identical whether in Scotland or England. The economy of the UK is one homogenous unit. Most large-scale enterprises operate both in Scotland England, as well as internationally, and most have headquarters in England or overseas. Financial institutions are run on a UK-wide basis and indeed operate on a global basis too. There is a common currency, the Pound Sterling, controlled by the Bank of England.

A new international border between Scotland and England

What would independence mean in reality? It would mean a new international border between Scotland and England, particularly if an independent Scotland re-joined the EU. In that event it would have to be a hard border of some kind, despite the enormous difficulties from hundreds of border crossings composed of anything from major motorways to back farm-roads.

Without a hard border, different regulations in environment, food and agricultural standards – and ‘divergence’ from the EU is the trajectory of the UK government – would mean that an open border would compromise the EU market. The difficulties around the Northern Ireland protocols within the December 2020 EU/UK agreement would be ten times worse in relation to the Scottish/English border, if Scotland re-joined the EU.

At best, the new border would resemble that between Norway and Sweden, a thousand-kilometre, overland border between two countries that used to be united, one of which is in the EU and the other not, albeit with treaty agreements with the EU. Even in this case, with the softest of ‘hard’ borders, there are checks and border posts on all the main routes.

Legitimate grievances over democracy in the UK

Those who argue for independence highlight what are legitimate grievances about the way our so-called democracy works. There is an offensive and chauvinistic arrogance about the rich capitalist elite which is concentrated in London and the South East of England. Scotland (and, we might add, Northern Ireland, Wales, the North of England and Cornwall) are treated as isolated peripheral regions.

We have an electoral system that consistently delivers UK results which are different to those in Scotland, even before the electoral victories of the SNP. These problems are not unique to or confined to Scotland, but apply in a similar form to other areas of the UK as listed above. Peripheral areas in the rest of the UK have the same or similar grievances.

The North-East of England had a much more consistent record of voting Labour than Scotland ever had. So had South Wales. In the case of the North East, as the Hartlepool and other elections show, the feeling of being ‘left behind’ or ignored by a London elite has expressed itself in voters turning away from Labour towards Brexit and the Tories. Even within Scotland itself, there are tensions between the centre and the periphery. There is a small separatist current in the Shetlands and in the Orkneys, both archipelagos having been parts of the Kingdom of Norway until the fifteenth century.

The creation of devolved assemblies in Wales and Scotland, with limited financial powers, has allowed some divergence in political and social questions, but the main levers of macroeconomic power remain pretty much with the UK Treasury. In Scotland, the Assembly, renamed as the Scottish Government, gave the nationalists a platform to air grievances and push an independence agenda. The constant refrain from the SNP is that the hands of the Scottish Government are ‘tied’ by Westminster, but in fact, in power, the SNP have not fully used all the fiscal powers granted to the Scottish Parliament.

2021 Election gives a clear mandate for second referendum

The SNP government that was elected in 2011 was acknowledged by the Westminster Government as having a mandate for a referendum on independence. Despite the bluster of Boris Johnson and the Tories today, it is hard to see – with a clear SNP-Green majority elected this May – how they could refuse a second referendum.

Given the clear mandate from the elections in May, it should certainly be the policy of the Labour Party, both in Scotland and in Westminster, to support a second referendum, as and when the Scottish Government decides. Ultimately, it should not be the government at Westminster, but a democratic vote of the Scottish people themselves that should determine whether or not Scotland becomes an independent state or remains in some form of union with England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

If and when a second referendum happens, all the old arguments will be aired, and many new ones besides. Debate will take place with a passion, and with Scottish people apparently split roughly 50:50, the outcome is in the balance.