By John Pickard

Although global warming as a major political issue is a relatively ‘recent’ one, from the point of view of the science, it has been around for a lot longer. Even then, as recently as a few years ago, it was thought that climate change, although important, would be more of an issue for the coming generations, not ours. Increasingly, however, it is looking like an issue for now.

There are a growing number of dire predictions which suggest that what is done, or not done, in the next ten years will have a crucial effect on the future of humanity. It all makes for pretty sombre reading, but it is vital reading, nonetheless.

In the last few weeks alone, we have had devastating floods in Central Europe, wildfires out of control in the Western parts of North America, flash floods in railway tunnels in China and many more disasters. In Northern Ireland, in a single week, there were three days of highest-ever recorded temperatures, each new record surpassing the last. The predictions of climate change have always suggested an increase in ‘anomalous’ and ‘extreme’ weather patterns and that is precisely what we are now seeing.

Is human civilisation destined to collapse?

A recent paper by Gaya Herrington (November 2020) looked at the next few years and makes for some grim reading. Herrington looked again at predictions that were made as far back as 1972 and comes to the conclusion that the pessimistic predictions from that time – for social break-down and disintegration – are broadly still applicable today.

That original 1972 study, by a team of MIT scientists, had a focus that linked resources, pollution and production more to population growth than climate change per se, but its conclusions, published as Limits to Growth (LtG) have largely been borne out. Their prediction that human industrial civilisation was destined to collapse sometime in the mid twenty-first century was widely discussed and derided at the time, but Herrington’s new examination of the 1972 study, its methods and above all the data, actually bear out what was said that the time.

She came to the awful conclusion that Business As Usual (BAU) is leading towards “terminal decline of economic growth within the coming decade” and, at worst, a societal collapse by around 2040.

The 1972 team generated different scenarios by using varying assumptions about technological development, amounts of non-renewable resources being used, and what were expected to be societal priorities. When the paper was published, its critics were scathing in their criticisms. They pointed to the great reservoirs of human ‘ingenuity’ and the ‘markets’ among other factors what would come to our aid.

Coal, oil and gas more plentiful than anticipated

Those who relied on the ‘market’ to save humanity assumed that an increased scarcity of carbon-based fuels would drive up prices and, through market mechanisms, push society in the direction of renewables. That has not happened, as we see, largely because non-renewables like coal, oil and gas, turned out to be more plentiful than was supposed fifty years ago. Because these industries are privately-owned and run for as much profit as possible in the shortest-possible time, they have careered on at full speed – and still do – to the extent that they have even suppressed research on global warming.

A 2014 re-examination of the original 1972 data and the BAU scenario indicated “a halt in the hitherto continuous increase in welfare indicators around the present day and a sharp decline starting around 2030”. Herrington’s 2020 study was intended to update the research further, examining whether or not BAU was still the predominant strategy being followed. What was perceived as a ‘pollution crisis’ in 1972 was re-interpreted as a crisis of climate change, as a result of greenhouse gas pollution.

Her research, using economic and scientific date up to 2019, recalibrated the 1972 data and although there were some different assumptions and tweaks that were necessary, the overall predicted outcome was largely the same. She concluded that despite some measures to ameliorate carbon emissions, principally by government actions, and some ‘greening’ of industry, Business As Usual is precisely what we still have.

Some climate change is already ‘baked’ into the system

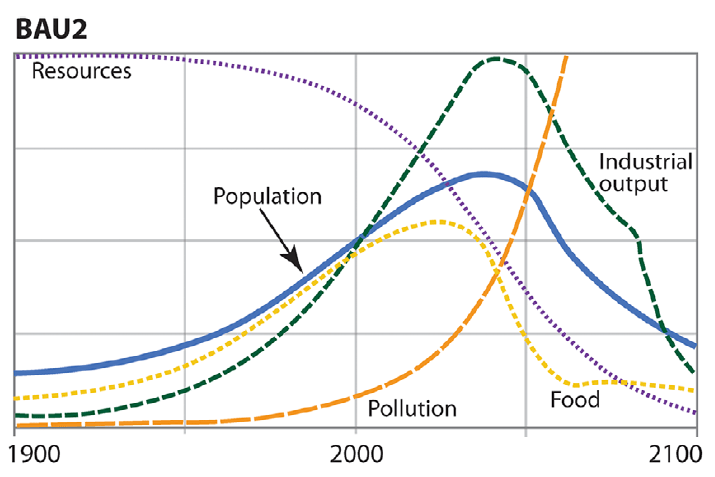

In fact, in updates that have taken place since 1972, the BAU assumption had to be corrected for an increase, not a decrease in the use of non-renewable, carbon-based fuels. This became, as Herrington terms it, ‘BAU2’, which offers a scenario worse than the first BAU (See chart for BAU2).

Nowadays, there are many scientists who are not only warning about climate change, but who have in effect accepted its inevitability. They are warning that we need to do two things – to continue to mitigate climate damage by shifting to renewables as early as possible, but at the same time prepare for the inevitable consequences of climate problems that are already ‘baked into’ the system.

One such gloomy paper is Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, by Professor Jem Bendall, who argues that “disruptive impacts from climate change are now inevitable” and that we need to find ways to plan for this.

Perilously close to, or already passed, a tipping point

Another study published by the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration, an Australian think-tank, describes a “near- to mid-term existential threat to human civilisation” and sets out what it describes as “plausible” scenarios if our current policy of business-as-usual continues for the next thirty years. The paper, Disaster Alley, Climate Change Conflict and Risk, makes for bleak reading indeed. These are some of the conclusions the paper draws:

- From tropical coral reefs to the polar ice sheets, global warming is already dangerous. The world is perilously close to, or passed, tipping points which will create major changes in global climate systems.

- The world now faces existential climate-change risks which may result in “outright chaos” and an end to human civilisation as we know it.

- These risks are either not understood or willfully ignored across the public and private sectors, with very few exceptions.

- Global warming will drive increasingly severe humanitarian crises, forced migration, political instability and conflict…

- Building more resilient communities in the most vulnerable nations by high-level financial commitments and development assistance can help protect peoples in climate hotspots and zones of potential instability and conflict.

This particular paper focuses on Australia and the manner in which its political and corporate leaders are “abrogating” their responsibilities, all the more so, seeing as South-East Asia may become “Disaster Alley” and may face some of the worst impacts of climate change.

Changes in societal values and priorities

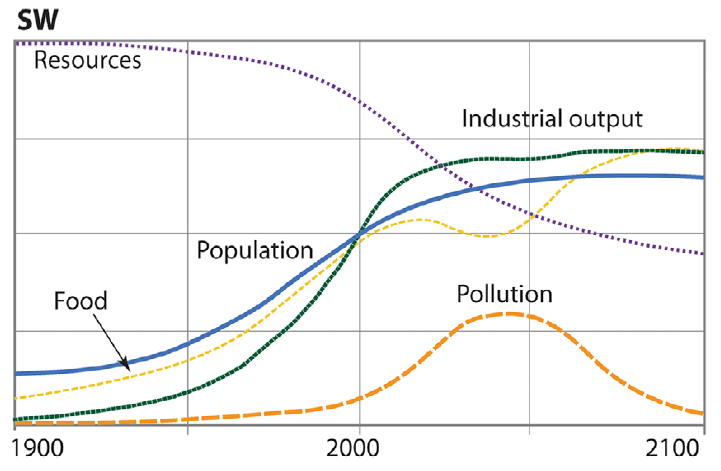

In Herrington’s paper, there is one assumption that leads to a slightly more optimistic scenario. This she calls ‘SW’ and includes a high level of development of science and technological innovations and, crucially “changes in societal values and priorities”. According to the SW scenario, “population stabilizes in the twenty-first century, as does human welfare on a high level” (see chart for SW scenario). In her conclusion she notes that the “window of opportunity” for this scenario is “closing fast”.

What Herrington means by “changes in societal values and priorities” is not spelled out. Unfortunately, as is the case with most of the dire warnings of climate change – from Extinction Rebellion to our own David Attenborough – there is no attempt to link the climate emergency to the system of economy within which it has matured. It is not just a matter of ‘mis-chance’ that carbon-based fuels have increased – and still increase – pumping carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

It is as a direct result of a system based on greed, profit and on maximizing short-term gain, whatever the cost to the future. It does not bode well for international cooperation on climate change when governments in the richer North back up their pharmaceutical companies in refusing to relinquish copyright on coronavirus vaccines, so that half of the world goes unvaccinated.

Vanity projects like billionaires’ space race

Changing the social system is not an optional extra – it is a vital and integral part of the fight to save the planet and humanity’s place on it. As long as investment, research, science, technology and industry are managed at the behest of a few dozen billionaires, there are no solutions. We will get vanity projects, like the billionaires’ ‘space race’, but no rational plan to deal with the climate.

It is always important for socialists to have a sense of perspective, so that we can understand what is going on around us, socially, economically and politically. We need to see the trajectory along which society and politics is moving. But we are no longer in a position where we can exclude climatic effects from such perspectives.

In ways that are unpredictable, at least in its details, climate change will have an impact on food prices, population shifts and directly in terms of natural weather disasters in the coming years. Those events will impact politically and in a big way. It may not lead to a sudden crunch and complete ‘societal collapse’ as the most pessimistic predictions would have it, but it would almost certainly lead to an ever-sharpening crisis and struggles for land, water, food and other resources. It is not a pretty scenario.

The fight for socialism, for democratic ownership and control of the main levers of production, distribution and exchange, has never been more relevant or urgent than it is today. It is not just a struggle for the next week or month – although for some people, living hand to mouth, it is exactly that – but for future decades and generations.