By Ian Isaac, former South Wales NUM Lodge Secretary.

On Thursday, Boris Johnson claimed that we started to transition away from coal in his lifetime, all thanks to Margaret Thatcher who closed so many coal mines. He then laughed. This was his crass attempt to gain some publicity for the UK ahead of the planned climate summit, COP26, in Glasgow in November.

“Look what we’ve done already. We’ve transitioned away from coal in my lifetime. Thanks to Margaret Thatcher who closed so many coal mines”. I doubt, fresh as he was from the elite playing fields of Eton, that Boris Johnson had even heard of climate change in 1984. To give the impression that the mines were closed as part of a transition towards zero carbon, is absurd and was no more than a smug journalistic throw-away remark, attracting another round of headlines as yet one more Boris Johnson gaffe.

When Thatcher set out in her quest to become PM in the late 70s, she was out to destroy the effective bargaining power of the unions, notably the miners: it was no transition towards reducing carbon. That the NUM was the biggest target in her sights was clearly laid out in the 1978 plan of Nicholas Ridley.

Thatcher was at pains to stockpile coal

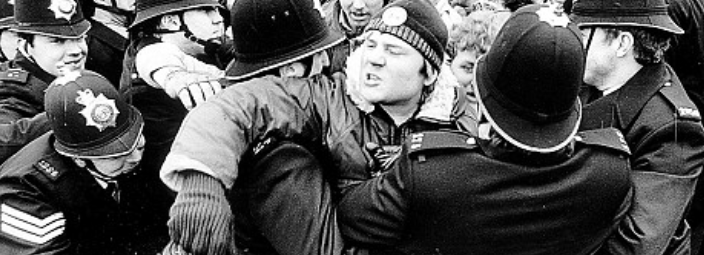

Thatcher’s strategy was entirely class-based and political in character. She had seen the miners defeat Ted Heath in 1974, when after the election the miners won a large pay award. So she set out to take on the miners only after stockpiling coal at the power stations, denying striking families social security, increasing the police forces and establishing a nationally coordinated police command body through the Chief of Police Officers National Association.

The Tories also introduced legislation limiting picket lines to no more than six pickets. They tactically conceded many industry-wide pay demands and resolved potential strikes and disputes in the car industry, the docks and among other sections of workers.

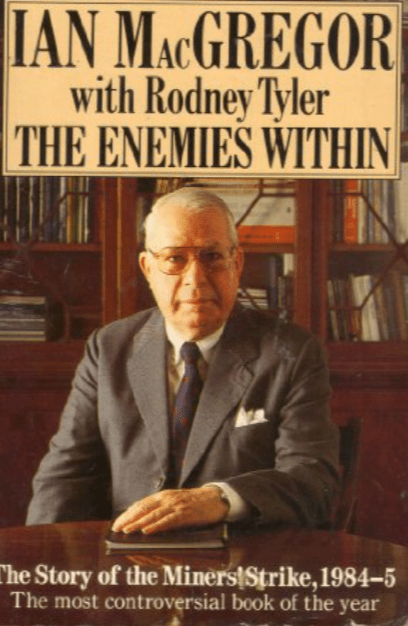

They imported a naturalised American tank-designer, Ian Macgregor, to be chairman of the National Coal Board. His daily mantra was “management’s right to manage” and to run the industry without reference to the needs of the mining unions who represented the employees in negotiating pay and conditions. More importantly, the unions had consented to the structure of the industry, based on the NCB, when it was nationalised after the War in 1947.

Macgregor didn’t want a National Coal Board he wanted a management board of control. When he got it after the 1984/85 strike was over, and with the NUM going back to work without agreement, he set about the complete destruction of the remaining 120 coal mines in the UK in 1984 and not as a ‘transitional towards reducing carbon’.

Such was the determination to destroy the NUM and its bargaining power that very little thought went into the impact this would have on the economy and life of the mining communities. Some regional development took place, with Sony in Bridgend and Revlon and Morris Cohen in Maesteg. There were similar strategies involving substantial grants to encourage “inward Investment” in Scotland, the North-East and County Durham.

Virtually no well-paid industrial jobs left

But over the last 40 years many of these so-called strategic industries have upped and left or are about to leave. Instead of replacing the 40,000 mining jobs that we had in South Wales in 1974, nearly 50 years on, there is virtually nothing in terms of well-paid industrial jobs to provided job opportunities for the sons and daughters and grandchildren of former miners.

All that exists in former mining communities and in the main city conurbations are gig economy jobs, delivery via agency and quasi self-employment. The main employment is in the public sector: in local government and the health and social care sectors. What industrial work there is, is organised via employment agencies who fire and rehire and cream off the pay of the employee.

There are virtually no former miners in employment now. Of those still alive, the majority are in receipt of disability benefits and are living off meagre pensions. Their communities are no longer the same environments, where people had looked out for each other. Some valiant examples of self-help groups remain, such as men’s sheds projects, and schemes funded by the Coal Industry Welfare organisation. There are some regeneration and supported employment training schemes funded by WEFO, the European funding body, but that is being wound down now due to Brexit. A small NUM office in Pontypridd continues to offer advice and support to former miners and their relatives. *

A transition to carbon-neutral to benefit the rich

None of this looks like a transition to the sunlit uplands of a zero-carbon, sustainable, social and economic system. Not at least one that benefits all according to their needs and allows them to contribute to the world of work and participate in community interactions according to their abilities.

It seems like we are on a transition to a zero-carbon economy that rewards only the wealthy and their representatives, in accordance to how they wield power and draw on the profits from investments in carbon-neutral energy production. One thing for sure is that despite some social cooperative project funded schemes with solar panels and wind turbines, the majority of green energy projects will be funded by the wealthy investors and pension funds in return for large profits as the primary aim. Not the aim of zero carbon.

Ian Isaac was formerly on the South Wales NUM Executive Council, as well as lodge secretary of St John’s NUM and Llynfi Valley joint lodges. He is also the author of When We Were Miners.

*For a comprehensive account of the impact of Colliery Closures, The Shadow of the Mine, by Huw Beynon et al www.versobooks.com