By John Pickard

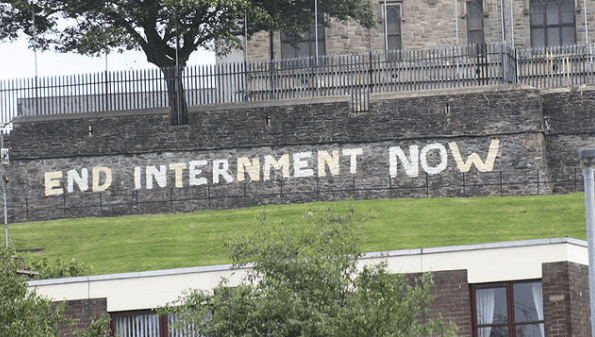

In the early hours of the morning, fifty years ago today, Operation Demetrius swung into action. In a huge series of dawn raids involving 3,000 soldiers of the British Army, internment without trial was re-introduced into Northern Ireland for the fourth time.

It was a desperate measure by the British and Northern Irish governments, supposedly to stem the growth of the IRA. But it had the result of doing the exact opposite – enormously enhancing the prestige, personnel and strength of the IRA, the Provisionals in particular.

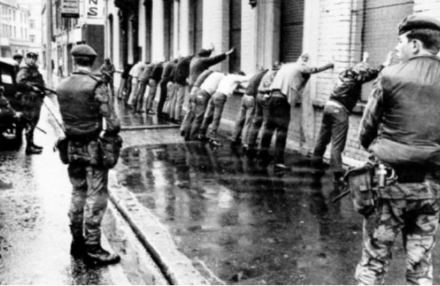

In all, around 340 men were rounded up by the Army in the first wave of arrests, of whom around 250 were detained indefinitely, the remainder being released after a few days. In their efforts to arrest members of the Provisional and Official IRA, the forces of the state rounded up hundreds of Catholics activists of all kinds, including, for example, members of the People’s Democracy Party and its leader, Michael Farrell.

Most of those arrested in the early hours of August 9 went straight to the prison camp at Long Kesh near Lisburn, and they were joined by dozens more in the following weeks. It wasn’t long before stories of ill-treatment and torture came out. Some prisoners were beaten, subject to sensory deprivation and others given mock ‘executions’ by being pushed out of helicopters hovering at ground level. As these stories filtered out, they incensed the Catholic population who were the exclusive victims of all the raids.

There were some early releases, an indication of the complete shambles of intelligence that had accompanied the raids, the Army using old and out-dated police data. Only a week after internment, the Provos Chief of Staff, Joe Cahill, was able to cock a snook at the British Army by giving a press conference in the heart of Belfast’s Ballymurphy district, in which he alleged that only 30 of those detained were PIRA members. The IRA, he said, was still ‘intact’.

The background to internment and the Falls curfew

Since the British Army had gone into the North in 1969, ostensibly to ‘protect’ Catholic communities under siege from sectarian mobs and the overwhelming sectarian forces of the Northern Ireland state – the RUC and the ‘B Specials’ – there had been a growing rift between Catholics and the Army. As Marxists had predicted at the time of the entry of British troops – most groups on the left having supported the Army deployment in August 1969 – the Army was increasingly seen as a vehicle of repression of the Catholic community, rather than its saviour.

One incident, in the Summer of 1970, became known as the ‘Falls Curfew’. In the wake of the IRA bombing campaign, the British Army instigated a series of searches in the Catholic Falls Road area of Belfast. After some skirmishes with residents in which shots were fired, the army used a massive show of force, with three thousand soldiers deployed in the area, imposing a curfew. The whole area was saturated with troops, CS was used freely and almost 1,500 rounds of ammunition were fired, killing four civilians, with no loss of life for the Army.

As Ed Moloney put it in his book, A Secret History of the IRA, “the operational distinction between ordinary Catholics and IRA activists became blurred.” The SDLP’s Paddy Devlin later commented in his autobiography, “Overnight the population turned from neutral or even sympathetic support for the military to outright hatred of everything related to the security forces.”

Right-wing split in the IRA

In the January of 1970, what became the ‘Provisional’ IRA had split away from the ‘Official’ IRA. It has often been forgotten, including by many on the left, that that the political basis of that split was completely reactionary. The Officials, who had developed an orientation towards class politics, were opposed to a campaign of bombings, because of the danger that it would provoke sectarianism between the two communities. Those who split away from the IRA, in contrast, were more traditional and conservative republicans.

In his book, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, the chief of staff of the new Provisional IRA, Sean MacStiofain, explained the rationale for the split: “We opposed the extreme socialism of the revisionists [the Official IRA leadership] because we believed that its aim was a Marxist dictatorship…” In the very first edition of a new publication supporting the Provisionals, Republican News, the editorial fulminated against “Red agents” and “Red infiltrators” in the old IRA.

Not surprisingly, it was the most right-wing and reactionary elements of the political establishment in the Republic of Ireland who were also instrumental in providing finance and weapons to develop the Provisionals as a counterweight to the ‘radicals’ in the Official IRA.

Provisionals launch bombing campaign

By January 1971, a year after the split, the Provisional wing had established itself as the leading part of the IRA, although not without a degree of internecine warfare. In April 1971, it launched a bombing campaign in Northern Ireland, aimed not only at all the forces of the state – Army, police and prison officers – but at the NI government and commercial properties as well. The aim was to make Northern Ireland ‘ungovernable’ so the British government would close down the Stormont government. To the Protestant community, this was a bombing campaign aimed exclusively at them.

The number of bombings, particularly in Belfast, rose dramatically, from 37 in April, to 47 in May, 50 in June and 91 in July, nearly two a day for four months. This coincided with the British army’s clampdown on Catholic areas, including the infamous ‘Falls curfew’.

In February, the first British soldier to be killed on active duty, Gunner Robert Curtis, was, by killed the Provisionals. Curtis was only the first of many British Army personnel to die in that year and the first of over 500 killed altogether.

In one particular episode, in March, which provoked considerable outrage, three off-duty Scottish soldiers of the Royal Highland Fusiliers, including two brothers aged 17 and 18, were lured away from a pub in Belfast and killed on the outskirts of Belfast. The IRA actually issued a statement denying responsibility, an indication perhaps of disquiet felt even within the Catholic community, but no-one believed the denial.

A continuous round of riots and communal disturbances

In both Catholic and Protestant communities, in the first half of 1971 there was a continuous round of riots and disturbances, the former against brutal raids in search of arms and IRA suspects, and the latter against attacks on police and prison personnel by the IRA and the bombing of Protestant businesses. In these circumstances, the Stormont Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner, had been demanding for several weeks running up to August, to be able to use British troops to intern suspected IRA members without trial. Finally, with the support of the British armed forces, his wish was granted.

“We are, quite simply, at war with the terrorist,” he declared on August 9, “and in a state of war, many sacrifices have to be made.” In Southern Ireland, the Taoseach, Jack Lynch, described internment as “deplorable evidence of the political poverty of Ulster’s policies.”

Whatever the intentions of the British and Stormont governments, without a shadow of doubt the main winners in the introduction of internment were the Provisional IRA. Their recruitment mushroomed, literally overnight. “Internment ushered in a new phase in the IRA’s development, especially in Belfast”, wrote Ed Moloney, “Its ranks were flush with new and angry members eager to strike back at the British, supplies of cash and weapons increased, particularly from Irish-Americans.”

In the immediate aftermath of the introduction of internment, there was a huge increase in civil disturbances, sectarian riots and violence in general. In their hundreds, both Catholic and Protestant families were bombed out of their homes where they had been minorities. Protestants were forced out of the Ardoyne area of Belfast, setting fire to their homes as they left, rather than leave them for Catholics to occupy. Two thousand Protestants were left homeless. An even greater number of Catholics – around 2,500 – left Belfast for refugee camps set up in the Republic in the South, as the Dublin government reacted to outrage within its own population.

Internment united Catholic community against British state

In the whole seven months leading up to August 9, 34 people had been killed in Northern Ireland, but within three days of internment, 22 were killed, and a further 118 for the rest of the year, an average of nearly one a day. “In Ballymurphy”, Ed Moloney writes, “British troops were involved in two days of savage gunfire and violence, which left a Catholic priest and 7 civilians dead.”

Internment united the Catholic community against the British state in a way that no other single event had done since partition in 1921, not least because it had been introduced in an entirely one-sided manner, leaving Protestant paramilitaries completely untouched. Operation Demetrius was directed entirely at the Catholic section of the population, although there were well-established Protestant paramilitary organisations, some of which had been active for a number of years. Not a single member of the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was arrested, nor any member of a new loyalist paramilitary, the UDA.

Three months later, in early December, the UVF bombed McGurk’s bar in Belfast killing fifteen people, including the owner’s wife and daughter. Up to this point, the McGurk bombing caused the greatest loss of life from a single incident. Yet it would still be more than another fourteen months – February 1973 – before any UVF member would be interned.

Tens of thousands of households on rent strike

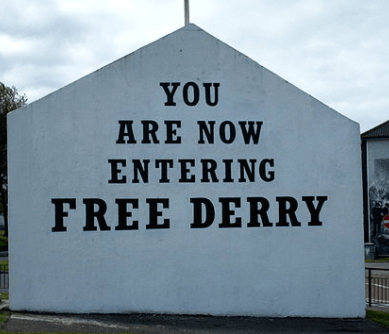

Every political party with mass support in the Catholic community was outraged by internment and there were calls for no-go areas to be established and new barricades were established. A campaign of civil disobedience was immediately launched, in Catholic areas by means of a rent strike. By the end of September, there were 26,000 households withholding rent, with some areas of Belfast giving a 100% support.

Scores of young men and women literally queued to join the IRA. From being a relatively small organisation – still at that point in competition with the Official IRA – the Provisionals became a far stronger, better organised and more potent force.

Filled with a new layer of angry, energetic, overwhelmingly young recruits, the Provisionals were able to expand their command and battalion structures across the whole of Northern Ireland and develop a far wider network of support among sympathisers in the Republic. Two years earlier, the IRA was lucky to be able to mobile 50 volunteers, but by the end of 1971, it is estimated the Provisionals had 1,200 members in Belfast alone.

It was as a result of the influx of members and the growth of its passive support in the community that the Provos were able to significantly expand their operations. There were nearly 200 bombings in September 1971, the first full month after internment. “In its official history the IRA claimed that all but a tiny number of the violent incidents, shootings as well as bombings, logged by the British Army after August 9 were its responsibility: 999 in September, 864 in October, 694 in November, and 765 in December.” (Ed Moloney). The total killed by the IRA was 86 in 1971, four times the number of the previous two years, while killings by the British Army rose to 45, six times the previous two years.

Biggest single political blunder

In hindsight, the strategists of British capitalism must have realised that they had made a serious mistake, perhaps the biggest single political blunder in modern times. In the short term, it led to a huge upsurge in violence of all kinds and hundreds of protests, including the one in Derry in January 1972 that led to Bloody Sunday when thirteen unarmed protesters were killed by soldiers of the British Parachute Regiment.

Internment lasted until December 1975 and during that time nearly two thousand people were interned, with Catholic internees outnumbering Protestants by nearly twenty to one. Even after 1975, there were restrictions on democratic rights and ‘normal’ court processes, so effectively political prisoners remained incarcerated, and this led to prisoners’ protests and the hunger strikes in 1980 and 1981.

Repairing the class divide the key task today

One of the worst features of the introduction of internment was the complete absence of a strong voice of opposition from a working-class standpoint. The Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions dodged any sense of responsibility for workers’ rights by refusing to take a position on internment, even though it rode roughshod over all the norms of democratic freedoms. The Northern Ireland Labour Party likewise kept its silence, effectively endorsing the move.

Few voices criticised internment from a class standpoint, one of them being the Marxist paper, Militant. “Internment”, it argued, in the September issue, “is not a religious but a class issue.” Referring to the rent strikes, it made the point that “…to be successful, the present struggle must be converted from a Catholic struggle into one of the working class as a whole. If it is not, all present efforts will be futile and will only make matters worse. Strikes where only Catholics are involved can create bitterness on the shop floor and can lead to intimidation and victimisation. No-one in the leadership of the present campaign has taken the trouble to spell out these dangers and the movement has been permitted to become sectarian.”

The tragedy of Northern Ireland has been an ongoing process of deepening sectarian divisions, extending over decades. Even today, as we mark the fiftieth anniversary of the introduction of internment, the single most important task for socialists and the labour movement is to make efforts to repair those divisions and build a movement based on working class policies to deal with working class needs. It may seem a daunting task, but there is no other alternative to further sectarian conflict.