Book review by John Pickard

Left Horizons has already carried articles on corruption in Afghanistan and the contribution that it made to the collapse of the US-backed regime. But this book, Thieves of State, by Sarah Chayes, a former US adviser in Afghanistan, brings that corruption into a lot sharper focus and looks at it in much greater detail.

We should make it clear to begin with that the author is no socialist. She was an adviser to the US military in Afghanistan and had been involved in several ‘anti-corruption’ working groups, regularly attending meetings in the White House and the Pentagon, quite apart from a variety of military headquarters overseas. Yet the whole tenor of her book is that the policy of the US and the West in Afghanistan (and elsewhere) actually promotes corruption.

Having initially gone to Afghanistan as a journalist and staying several years, working for an NGO in Kandahar, she soon became acquainted with problems brought to her (as an American) by village elders. In one instance, they were angry at locals being driven off their land. And so, on only the second page of the first chapter of the book, we get straight into it:

Shakedowns at every checkpoint

“President Hamid Karzai’s younger half-brother, Ahmed Wali, had claimed dozens of acres in the watershed of their precious spring as eminent domain – and then proceeded to sub-divide it and sell it off like his own private property. Bulldozers protected by police brandishing AK-47s and driving US-supplied Ford Rangers had carved up the land”.

And so the stories, and the detail, continue through the book. Farmers importing produce from across the border in Pakistan must pay off the goons in uniform at every military checkpoint, which meant bribing eight lots of soldiers in one sixty-six-mile trip. Casual shakedowns by thugs in uniform, might happen on any day, on any pretext. Object, and you might be beaten up, jailed, or worse.

The corruption constantly corroded public support for the government and increased support for the Taliban. “The government doesn’t hear our voices,” one village elder told Sarah Chayes, “The government doesn’t do anything, it’s just there to fill its own pockets.” Nor did it enamor the locals to the Afghan army or the UK/US forces who were seen to be turning a blind eye. “If I see someone planting an IED [improvised explosive device] on a road,” oneaggrieved Afghan put it, “and then I see a police truck coming, I will turn away. I will not warn them.”

Corruption paid for by the US taxpayer

Other examples of corruption related to investments in public infrastructure, all paid for by the US taxpayers. In one case, an important bridge was in need of repair, so that farmers could get goods in and out of their area.

“That bridge was a constant affliction to Kandaharis. People would trade figures on how much money had been allocated for the repair. They knew how the scam worked: the well-connected outfit that had won the contract would transfer it to a subcontractor – pocketing a percentage. That subcontractor would had the deal off to a sub-subcontractor, also minus a cut, till the company actually doing the work received only a fraction of the initial contract and threw something together with shoddy materials and underpaid workers. Meanwhile, cocky young employees of the companies up the line would thrust around town in slick SUVs worth years of an ordinary farmer’s harvest.”

This might be considered to be ‘corrupt’ (as indeed it is) by our author, but it is not dissimilar to common practice in Britain – and no doubt the USA – where public contracts are concerned. Think road pot-hole ‘repairs’ that last a fortnight.

Corruption from top to bottom

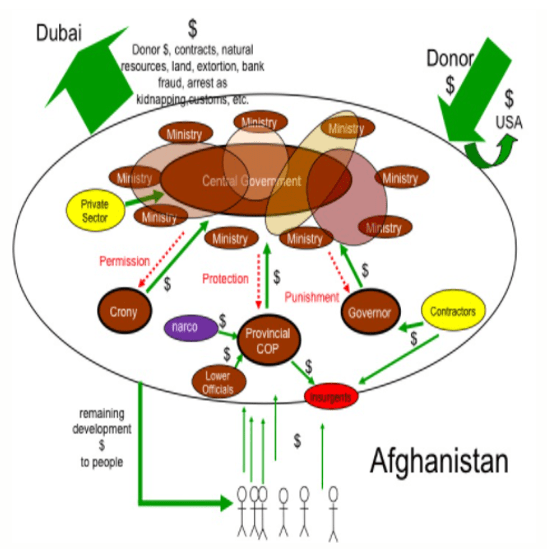

Neither was it just a case of a few rotten apples at the top creaming off the surplus. There was an entire infrastructure, with mid- and lower-level corrupt officials, all tied into the various scams. It was through these intermediate level, corrupt officials, Chayes found, that the US government worked. “We communicated almost exclusively with government officials, delivered development resources through their agents, hired their relatives and cronies, bought travel and T-walls and gasoline and intelligence from them, and often used armed thugs – known as private security companies – to protect our convoys.”

This meant that the corrupt officials were able to suppress any critics or deal with any would-be rivals, by fingering them to the US military as ‘Taliban suspects’ and leaving the US forces to deal with them: “we allowed them to credibly threaten to punish dissenters with a US Special Forces night raid,” she writes.

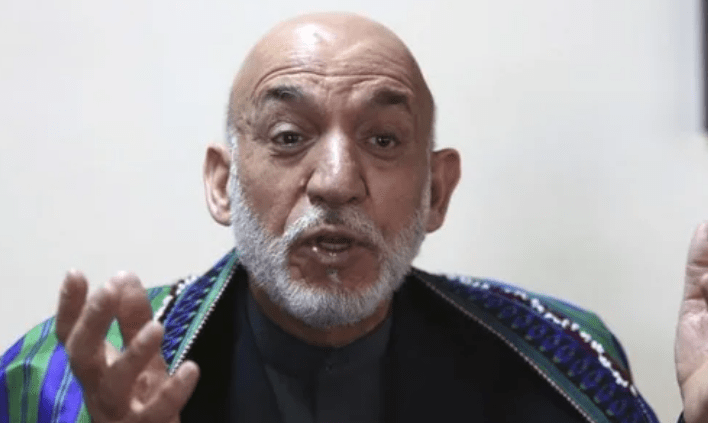

By appearing to side with the government and doing nothing to stop wholesale plunder by a government kleptocracy, the US/UK forces were seen by the local population as equally culpable. There were some half-hearted attempts at ‘dealing’ with corruption, by means of special task-forces – invariably advised by Sarah Chayes herself – but they did not have a single success. Every time a key official was arrested on suspicion of corruption, he would be released at the insistence of President Karzai, or a regional police chief.

Karzai, who was Afghan president for thirteen years up to September 2014, and who had Kabul airport named after him (up to the Taliban takeover) was completely immune, even though everyone knew he was corrupt. Chayes quite explicitly says that Karzai sat at the top of what was no less than a mafia-style organisation, where money was stolen and passed up the chain, in return for favours and protection from those above. She even produced graphs and charts for the US military, to illustrate the upward movement of money. (See image above)

Illusions in a ‘clean’ capitalism

The author’s outlook and her proffered ‘solutions’ unfortunately show a profound misunderstanding of the whole nature of capitalism and the role of the US and UK in Afghanistan. She clearly has illusions in the possibility of a ‘cleaner’ intervention, even though she catalogues the way in which the CIA, for example, actively promoted corruption.

“The CIA was paying one of my prime targets – I had seen it with my own eyes – Karzai’s younger half-brother, Ahmed Ali, who pulled the strings to most of southern Afghanistan, who stole land, imprisoned people for ransom, appointed key public officials, ran vast drug trafficking networks and private militias, and wielded ISAF [the international forces] like a weapon against people who stood up to him. The inhabitants of three provinces hated him.”

CIA operatives even sat in on official ‘anti-corruption’ taskforce meetings – not to add anything, but, sitting quietly, to take note of what was going on and which of their contacts was under threat. Unfortunately, what does not occur to Chayes is the blindingly obvious – that all the noise made about ‘combatting corruption’ was just for show, for public consumption, and that the real policy of the US government was what was being done by the CIA.

Corrupt leaders feted and supported by the West

The subtitle of the book, Why corruption threatens global security, reveals the illusions that Chayes has in the system. She gives a short analysis of corruption in other states – Egypt, Tunisia, Uzbekistan and Nigeria – where corrupt government were also celebrated and supported by the West.

An important argument in Sarah Chayes book – and in this, she is correct – is that the surge in radical Islam in many of these countries, not least in Afghanistan, is a direct product of corruption, because the Islamists portray themselves as being free of corruption, in contrast to the decadent hangers-on of the USA and the West.

What she is yearning for, however, is something that is impossible to get – a global financial and political system that is based on capitalism…yet is not corrupt. She even argues that most of the money being squeezed out by corrupt officials at the top of governments ends up in banks in places like the USA and London. That being the case, it is likely that the financial institutions, and Western governments, are aware of this flow of dirty money, but do nothing to stop it.

By a threat to ‘global security’ in the subtitle, the author means a threat to the stability of the capitalist system. Socialists would argue, however, that it is the inner workings of that system that breed corruption.

It is notable in this book that although corruption is finely documented, it is seen as a problem specifically for underdeveloped countries. There is not even a hint of the blatant corruption, for example, of the US Congress, where politicians are in the pockets of big corporations and banks and where there are ten times as many ‘lobbyists’ as there are politicians.

Or in the UK, where we have seen the Government’s response to the Covid pandemic is to throw billions of pounds at the friends and family of ministers and to supporters of the Conservative Party.

An entire system thriving under a veil of secrecy

Secret meetings go on all the time between Government ministers and their business partners. Government policy is dictated by business links and pressures not in the least by public need. To protect it all, the entire system operates under a veil of secrecy, whether it is tax-dodging, contracts to friends or dirty money sloshing around Western banks.

Both in the UK and in countries like Afghanistan, corruption is systemic and, in both cases, the detailed mechanics of the scams are kept well away from public gaze. The only real difference between Afghan-style corruption and the UK variety is that the former might profit a relatively narrow layer in society, whereas in the UK corruption benefits an entire class of capitalists, hedge-fund billionaires and landowners, and a wide layer of hangers-on. Moreover, their system is facilitated by centuries of experience in legal pretexts, arcane company law and a thousand and one tax dodges.

In one very telling sentence, Sarah Chayes describes “extreme cases” of corruption as those, “where the whole of government has morphed into a criminal organisation bent to no other business than personal enrichment.” That reminded me of a sentence written more than a hundred and seventy years ago, by the great founders of scientific socialism, Marx and Engels, writing in the Communist Manifesto: “The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”

We are actually very familiar with that concept here. Whether it is the tens of billions going on HS2, multi-billion government defence contracts, or just a local government contract to fix potholes, the mentality of British capitalism is that someone has to make a fast buck out of the public purse. And that is done by skimming a good profit, paying the lowest wages possible, and by using the cheapest materials available. And so what, if the end product is second or third rate? It just means another contract further down the line. They are thieves of state indeed, but not just in Afghanistan.