Gray Allan – Falkirk West CLP

Ninety years ago this month, the battleships, battlecruisers and heavy cruisers of the Royal Navy’s Atlantic Fleet were at anchor off Invergordon in the Cromarty Firth. At 0800 on Friday 15th September, ratings and stokers on several major ships failed to carry out their duties in preparing to put to sea for exercises. The Invergordon Mutiny had begun.

The Communist Party later reported that the mutiny “was led by Communists” and that the men of the Atlantic Fleet “had taken over the ships”. Anyone reading these reports could be forgiven for thinking that the battlecruiser Hood was about to steam south at flank speed with the red flag flying from her mainmast, enter the Thames and at the Pool of London, train her fifteen-inch batteries on the Palace of Westminster and Whitehall and demand the capitulation of the Government! Hardly!

But the stories of committees, preparations, plotting and secret signals, along with accounts of the men marching off the playing fields after a mass meeting singing “The Red Flag” all became part of the mythology of Invergordon. The mutiny was no attempt at a political revolution. It is more accurately understood as the high point in a long-running pay dispute with origins that go back to 1919 and the end of the First World War.

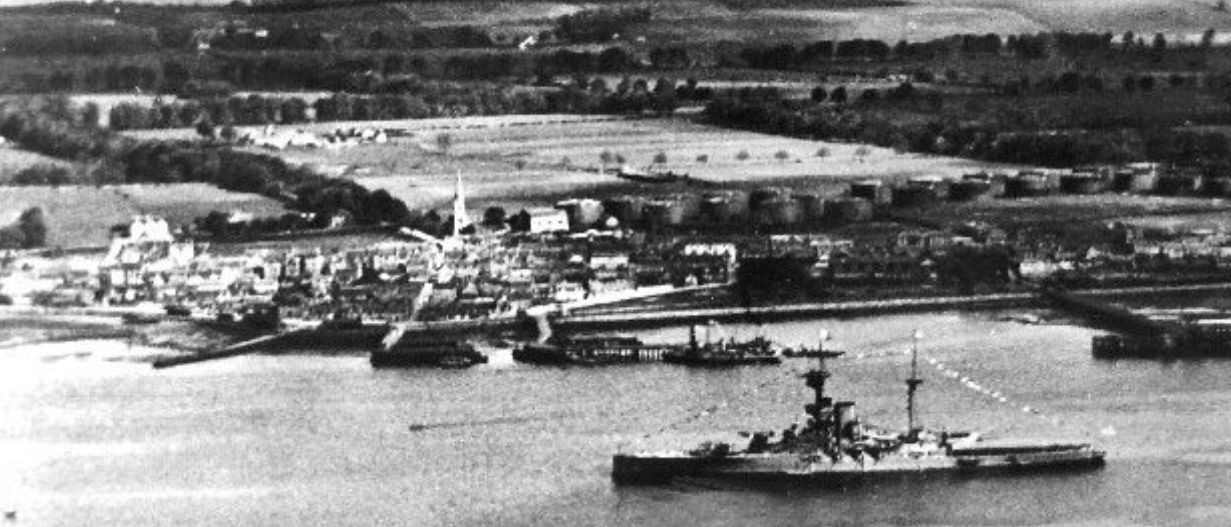

On the east coast of Scotland lie 5 great estuaries or firths, one of which is the Cromarty Firth, some 10 miles north of Inverness as the crow flies. There on the north shore sits the town of Invergordon, with its deep-water port and the oil rig construction yard at Nigg. Invergordon was an important base for the Royal Navy from 1914 until after the Second World War. In 1931, a number of navy men had their homes and families at Invergordon.

Furious seamen read of pay cuts in the newspapers on arrival

On Friday 11th September 1931, the capital ships and heavy cruisers of the Royal Navy’s Atlantic Fleet arrived in the Cromarty Firth from their home ports on the south coast of England. Their purpose, to carry out their regular exercises in the North Sea. This was to be no routine visit. The men on the lower decks were absolutely furious.

They had learned from newspaper reports that their pay was to be cut by one shilling a day. Along with a consolidation of pay rates some longer serving seamen were facing a pay cut of up to 25%. The Admiralty had intended that this news would have been given to the men by the captains of the various ships, who should have been sent a signal with a detailed explanation of the pay cuts. However, in a bureaucratic bungle, the signals were sent to the wrong ship. Rear Admiral Wilfred Tomkinson on the Hood, the commanding officer, got a very sketchy briefing two hours before sailing and of course, the press had the story in full well before the navy’s official briefing of its men.

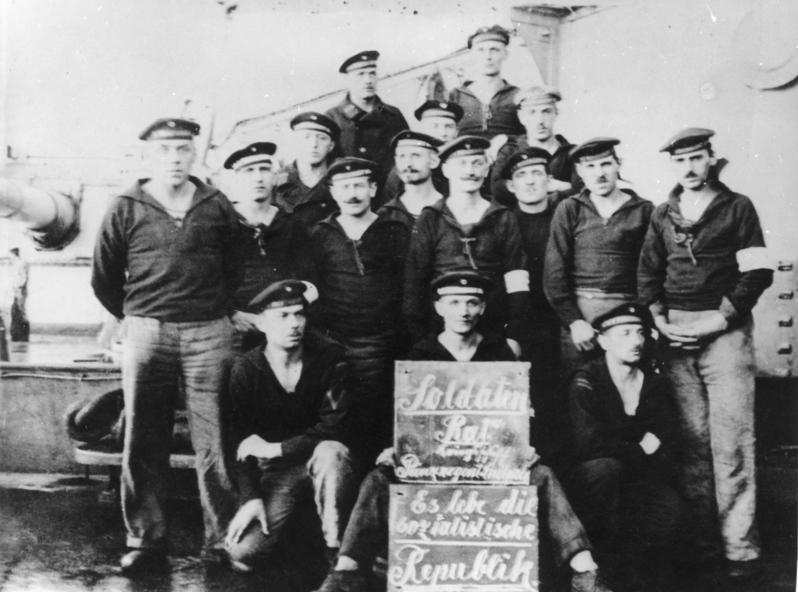

This was not the first time that the issue of pay had caused serious trouble in the Royal Navy. In 1918 and 1919, there had been general unrest in all services, against the backdrop of strike action in many industries and of course the Russian Revolution and the mutiny in the German Navy leading to the revolution of 1919. The situation was particularly bad in the navy. Pay had not been increased since 1912, apart from a twopence per day increase in 1917.

Lower deck agitates for a pay rise

In the period up to the beginning of 1920 the ‘lower deck’ agitated for a pay rise. Ratings and petty officers flooded into the lower deck death benefit societies, which had been agitating for the right to represent their members on welfare matters. These societies were being more and more thought of as trade unions. The Admiralty and the government were well aware of the seriousness of the situation.

A committee of enquiry was set up under Rear Admiral Sir Martyn Jerram. In an unprecedented move, the Committee included a number of lower deck representatives and took evidence from selected ratings. With mass meetings taking place in defiance of Kings regulations, the Admiralty acted unilaterally and awarded an interim pay rise of one shilling and sixpence per day. They were feeling the pressure.

On 11th February 1920 the Second Sea Lord wrote a memo to his fellow members of the Board of Admiralty

“…in my opinion there is no doubt that an organised attempt is being made by socialist and syndicalist circles to introduce into the Navy a lower deck union on trade union lines…if we do nothing there is the possibility that the lower deck trade union will become an accomplished fact…If we allow the men a recognised means of presenting their grievances, real or imaginary – and aspirations collectively, I believe the danger of an unauthorised Union will be averted”

So, in February 1920 a Welfare Committee was set up. Comprised of Admiralty officials, it was to meet annually and hear proposals from selected lower deck spokesmen on improvements to pay, terms and conditions. However, the Jerram Committee had already published its report, fixing a seaman’s pay at four shillings per day. The interim pay rise had been consolidated into basic pay but no new money was on the table. This was a bitter disappointment and caused further serious discontent. But now apparently there was the new Welfare Committee with whom the grievance could be raised.

Seamen delegates walk out of the Welfare Committee

Bur the Admiralty was now in no hurry to deal with the pay issue. Like any employer, once the immediate pressure from the workforce abated, they began to renege on their promises. The Welfare Committee began its work in October 1920. It immediately ruled that requests previously presented and turned down could not be re-submitted. Lower-deck representatives walked out of the committee in disgust.

Talk started again among ratings of the need for a real trade union. The Admiralty acted decisively and issued a fleet order forbidding the amalgamation of the Death Benefit Societies into a trade union and further excluding them from any welfare role. The men turned away from the societies, knowing that the employer was watching them carefully

As the short post-war boom turned to recession, the focus turned from winning pay rises to preventing pay cuts. In 1923, the view developed in the government that as the navy had no problem recruiting men, pay levels must be acceptable. Again, the men of the lower deck organised, the societies sprang back to life, MPs were lobbied and promises made, that cuts to naval pay would be opposed.

The Admiralty response was entirely predictable. The King’s regulations forbidding combinations of sailors was read out. It became a punishable offence for a sailor to approach an MP on a service matter. Officers were ordered to attend all future death-benefit society meetings as observers. This was the end of the lower-deck societies.

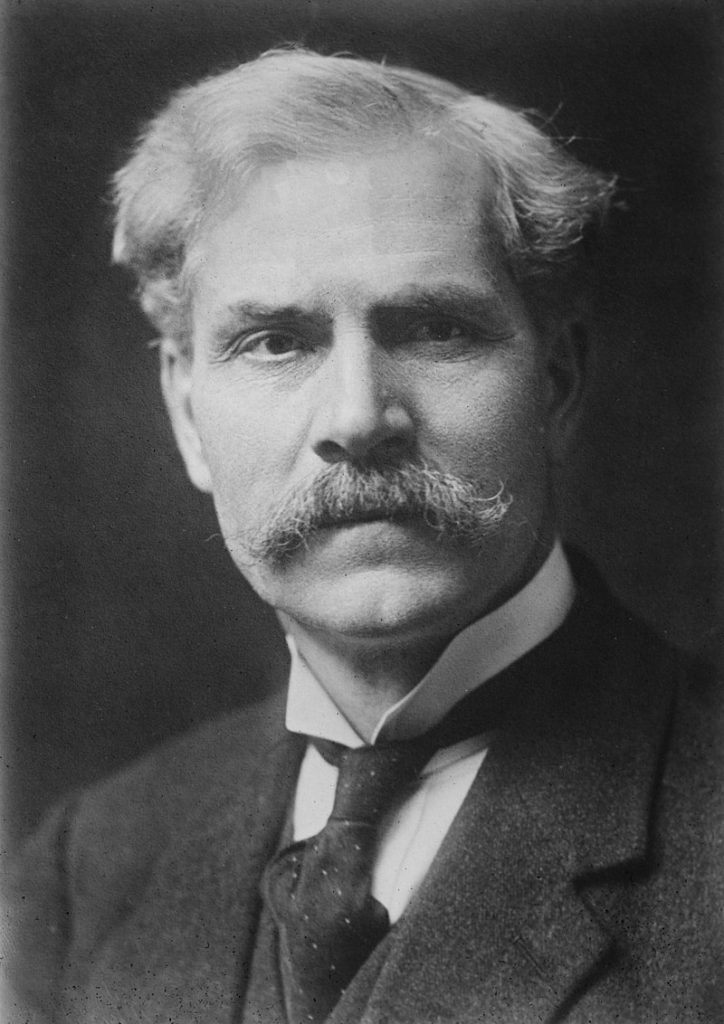

The only man in the Admiralty with the stature to stand up to the pay cuts, First Sea Lord Admiral David Beatty, “The Hero of Jutland”, said absolutely nothing. Pay was cut by one shilling a day but for men joining after 1925! This was despite promises made, by both Labour and Tory governments, not to cut wages.

However, pay for sailors on the old 1919 rates was protected. With a stroke of supreme stupidity, the Board of Admiralty had now implemented two rates of pay for men doing exactly the same work. They then compounded the error by bringing in different pension rates. By the late 1920s a keen observer could see real cuts in the standard of living of the men on the lower decks.

The recession deepens and cuts in public sector pay are called for

As the recession deepened into the Great Depression, the Labour government set up the May Committee, which recommended major cuts in public expenditure including wage cuts for civil servants, teachers, the police and the armed forces. For the Navy, the lower 1925 pay rates were to be applied to everyone as well as the poorer 1930 pension rates.

The ratings studied the May Report closely, far more closely than their officers did. The majority of the men were senior hands who had joined before 1925, indeed many were aware of, or involved in, the agitation in 1919 that lead to the pay rises then. But by August 1931 the Labour Government had fallen, with nine cabinet ministers refusing to accept the cuts. On 24th August Ramsay Macdonald formed the National Government with the Tories and Liberals.

During their seven-week summer leave in 1931, the men of the Atlantic Fleet would not have failed to see the demonstrations and protests by workers against the cuts in pay and benefits or the political upheavals in London. This was the tinder box awaiting a spark that sailed into the Cromarty Firth during Friday 11th September.

There had already been trouble over pay. The sailors of the destroyer flotillas, based at Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, had protested at a NAAFI meeting ashore, with the NAAFI rep calling for the pay cuts to be resisted. By Sunday the lower deck was fully informed about the pay cuts – not by their employer, the Royal Navy, but by the Press. Even worse, the cuts were to be implemented in two weeks’ time, leaving no time for men to sort their finances. There was uproar, soto voce on the ships moored in the Cromarty Firth but in full throat in the NAAFI canteen in Invergordon.

A “show” to get the Admiralty to cancel the pay cuts

When in port, half the ships company at a time were allowed shore leave or “liberty”. Liberty men gathered in the NAAFI canteen in Invergordon on the Saturday. All talk was of the pay cuts. On the Sunday a drunken rowdy crowd assembled in the NAAFI. Speeches were made but, according to witnesses, were mostly inaudible. That sailors under Kings regulations were prepared to speak in this way in itself was remarkable.

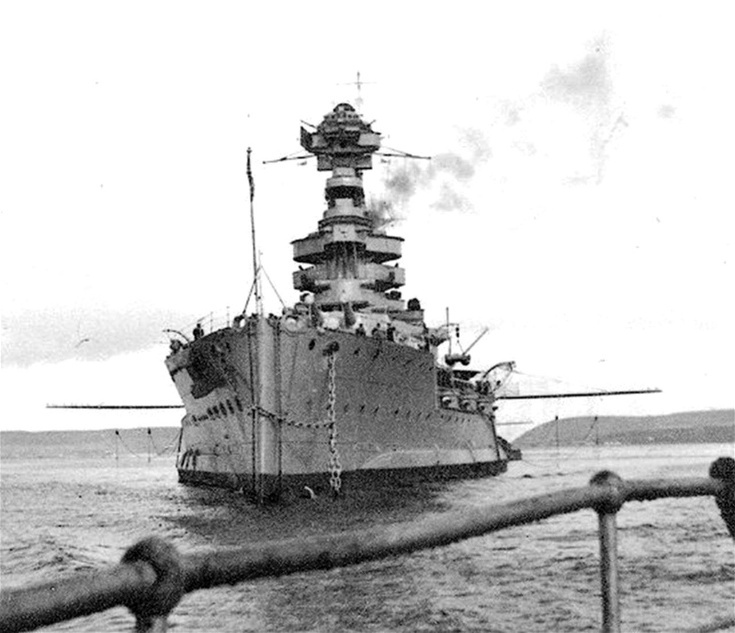

The feelings were that some kind of show had to be made to get the Admiralty to stop the pay cuts. The simplest thing to do was refuse to put to sea on the Tuesday morning. The ratings did not know what the sailing directions for the individual ships were, so could only look to the flagship HMS Valiant and take their lead from her crew.

The remainder of the liberty men had their chance to go to the NAAFI on the Monday. Again, there was a large gathering but this time the men were far more sober. They gathered in groups by ship and talked about the pay cut and the protests. These talks continued aboard their ships. By this time the battleships Warspite and Malaya had already put to sea for exercises.

HMS Valiant refuses to sail, cheering breaks out across the Fleet

On Tuesday, the battlecruiser Repulse put to sea at 06:30 with no protest. The main units were due to sail from 08:00 onwards. All eyes were on Valiant. It was clear she was not preparing for sea. Ratings were not working the main derrick to hoist the picket boat, which was left hanging on its falls. Cheering broke out from the seamen on the other ships – the mutiny had begun!

The high point of the Invergordon Mutiny was this period between 0800 and 1000 on the 15th. When it became crystal clear that the fleet could not sail, Vice-Admiral Tomkinson recalled those ships already at sea, the Warspite, Malaya and Repulse. Once back in port, their lower decks also agreed to follow the lead of the Valiant.

The next two days were filled with great anxiety. Having made their protest, the men were expecting a swift reply from the Admiralty. None came. In some ships the seaman carried out harbour duties. In others very little work was done. On Hood and Dorsetshire a ‘make and mend’ was ordered, which, in effect, means time off work for the ratings to attend to their own kit. This avoided a direct confrontation. In every case, essential work to maintain the safety of the ships was done. Auxiliary engines and generators kept running. Men avoided the officers so that they would not get direct individual orders. It was reported that officers were treated with respect.

At long last, the Admiralty realised the seriousness of the situation and ordered the ships to return to their home ports where the grievances would be looked at. This caused initial disagreements among the ratings. Some feared that instead of sailing home the ships would be scattered to Scapa Flow or Spithead where they would be boarded by marines and dealt with severely. Nevertheless by 22:00 on 16th September 1931, all ships had departed for their home ports.

Vice Admiral recommends cancelling the abolition of higher 1919 pay rate

The mutiny was a partial success. Vice Admiral Tomkinson recommended that the abolition of the higher 1919 pay rate be abandoned, that the two rates of pay continue and that only the 10% pay cut be applied to all rates as had been for all the public services. The Cabinet agreed. The Admiralty had promised no reprisals, although naval intelligence had prepared a list of some one hundred and twenty ratings, leading seamen and royal marines.

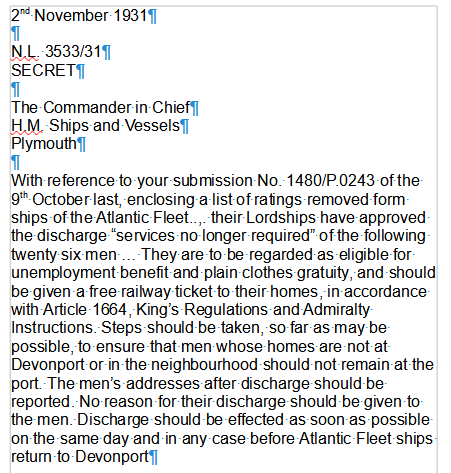

Despite their best efforts, they could not find the ring-leaders because there were none to be found. Ultimately, twenty-six were discharged as ‘services no longer required’, given no explanation, just their train fare home. AB Len Winscott, of the heavy cruiser Norfolk, who had been one of the spokesmen on his ship, joined the Communist Party some time after his discharge.

The party published a leaflet in his name in which they claimed the leadership of the mutiny. But there was no overall control. Once the men had decided not to sail, each ship acted on its own. The actions needed to stop a ship sailing were very simple – don’t light the boilers, don’t raise the anchors. No detailed planning was required. The Norfolk in any case was not one of the principal ships involved in the action.

A set of demands on pay, written either by Winscott alone or with Fred Copeman and others, was done at the suggestion of an officer, who provided his typewriter for the job. This manifesto was not seen by men on the other ships. It was published in the Daily Herald after the mutiny had ended, then much later in the Daily Worker.

Len Winscott eventually fled to the USSR. He survived the siege of Leningrad and ten years in the Stalinist Gulag, accused, ironically, of being a British spy. On his release, he lived in Moscow and was a friend of Donald McLean, the spy. Fred Copeman went on to command the British Battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

Fruitless hunts for Communist conspiracies and revolutionary sailors

Two spectres haunted Invergordon; one of a communist conspiracy, the other of the supposed ranks of revolutionary sailors. In their patronising arrogance, the Board of Admiralty could not accept that the men of the lower deck had the ability to organise such a strike. There had to have been an outside conspiracy. Naval intelligence hunted high and low but could find none.

The Communist Party, on the other hand, taken completely by surprise, send cadres to the naval ports to look for revolutionary sailors. They could find none. But, like a scene from a farce, the Communist Party cadres and the intelligence officers stumbled into one another! Two party members, Shepherd and Allison, were charged with attempting to incite mutiny and got lengthy jail terms. Another, Stephen Hutchings, a journalist for TASS, fled to the Soviet Union never to return home. In 1976, John Gibbons, the Party organiser for the South Coast, wrote in a letter to the historian Anthony Carew that in the period from 1931 to 1935 they did not recruit a single serving sailor!

In 1931, the Royal Navy and its capital ships was seen as the ultimate deterrent. These were the most powerful weapons of their day, capable of raining down one-ton armour piercing shells on targets at ranges of up to twenty miles. Their names were widely known. They were the Trident submarines of their time. The mutiny at Invergordon sent shock waves through the London Stock Exchange, which caused a run on the pound and ultimately forced Britain off the gold standard.

The significance of Invergordon

Marxists have a responsibility to describe events as they were, not as we would wish them to be. The Invergordon Mutiny did not have overtly political aims. It is best understood as an industrial dispute over pay. It shows that the men in the armed forces, while difficult to organise, were profoundly affected by events in the wider labour movement. It was a spontaneous outburst driven by over ten years of broken promises and appalling management. It was inflamed by the closure of every channel the men had to raise a collective grievance. And it was bolstered by the tremendous sense of solidarity to be found in a large and close-knit workforce, such as the crew of a battleship.

Invergordon is nonetheless significant for all that. Sailors took their stand, well aware of the forces ranged against them and the harsh penalties of the King’s regulations that they were breaking. These could in extreme circumstances have included the death penalty. Strike action by the men of the lower decks in the capital ships of the Royal Navy at Invergordon on 15th and 16th September 1931 deserves its place in the history of the struggles of the working class.

Sources

Anthony Carew; The Invergordon Mutiny 1931, Long term Causes Organisation and Leadership in International Review of Social History vol 23 no.2 1979

MacDonald H & Yeoman L; Respectful Rebels: The Invergordon Mutiny & Granny’s MI5 File

Admiralty Record ADM178-113: Invergordon Incident 1931 – Discharged Men