By Ray Goodspeed (Leyton and Wanstead CLP)

Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2019), drawing on the author’s own research, is an investigation and analysis of the extent of antisemitism, including pogroms, within the Red Army and among Bolshevik activists, and the response of the Bolshevik (later, Communist) Party leaders and official bodies to these attacks. It also deals with the role of Jewish socialists themselves, often non-Bolshevik, in fighting against antisemitism and in pushing the Party and the state to take more active measures against it. It makes extremely uncomfortable reading, even 100 years later, for any socialist who has been inspired by the events of the Russian revolution, but nonetheless, historical reality needs to be faced.

It is a fine example of the investigation into the reality of revolution and civil war that has been made possible by the release of document archives from the Soviet period since that system collapsed. McGeever’s research predates recent controversy around antisemitism and the Labour Party. This book is not a comment on that, but it has inevitably made it more topical. He is clearly on the left. I first heard him present the material of this book during a series of lectures in 2017, by Marxist and/or socialist historians, celebrating the centenary of the Russian Revolution, but also subjecting it to detailed, rigorous analysis.

Appalling oppression

‘Red antisemitism’ is discussed in the wider context of the appalling oppression suffered by Jewish people and their communities under the Czarist Empire. This included state-sponsored antisemitism, proudly urged on by the Orthodox Church, hundreds of discriminatory laws limiting residential rights to particular areas, such as the Pale of Settlement (ie the western borderlands of modern Poland, Belarus and the Ukraine – see title picture), as well as restrictions on occupations and other petty humiliations.

But far worse were the regular outbreaks of looting, violence and random mass murder of Jews – the pogroms – carried out by armed mobs of Russians or Ukrainians, urged on by the most reactionary forces in Russian society and either ignored or encouraged by the state and Church.

During the Revolution and Civil War (1917-21), these murderous attacks reached an appalling peak, as Jews were targeted both by the White (anti-Bolshevik) armies and independent armies of nationalist peasants, but also by detachments of the Red Army itself, as the front line moved backwards and forwards. An estimated 100,000 Jews were killed in pogroms during this period, possibly many more – the worst-ever attacks, before the Nazi Holocaust.

McGeever is clear that the vast majority (91%) of pogrom murders were carried out by Whites or nationalists. But that still leaves, astonishingly, many thousands of murders carried out by the Red Army or its allies. Incidents of ‘red pogroms’ occurred throughout the civil war period in many different parts of the former Russian Empire, but there were two major periods, in the spring of 1918 and the spring/summer of 1919, both in the Ukraine, involving thousands of Jewish deaths.

How could this be?

How could this be, when the Bolsheviks and every other left party had had a clear position against antisemitism for decades, and when many of them, including the Bolsheviks, had Jewish members in leadership roles at every level of their parties? In 1917, between the February and October revolutions, left parties, including the independent Jewish-left parties, worked on a united front basis to oppose these poisonous ideas.

Moreover, the revolution, at a stroke, swept away all of the hundreds of anti-Jewish laws. To that extent this period ushered in unprecedented freedoms and the period from the revolution to the end of the 1920s is widely regarded as a time of renaissance of the Yiddish language and Jewish culture and literature.

The answer partly lies in the nature of the Russian Empire itself. Antisemitism was not a fringe belief but was endemic to Russian society, part of the cultural and religious identity of the nation, particularly (but not only) in the vast countryside, where life went on largely in remote and isolated small settlements.

Even in cities, most workers were either newly arrived peasants, or one generation removed. Illiteracy was the norm; roads and transport links were appalling, and most areas did not have electricity, telephones, etc. When the red pogroms happened in early 1918, it took four weeks for the central Soviet government to even get the news!

Especially in the Ukraine, the split between urban and rural settlements could take on a nationalist and antisemitic flavour. Most people who lived in urban centres were Russian or Jewish, speaking Russian or Yiddish. The rural peasants were generally Ukrainians who often saw themselves as “hard-working, honest Ukrainian farmers, exploited and robbed by the lazy merchants, swindlers, and speculators who were Russian ‘foreigners’ or ‘despised Jews’, even though the rising industrial working class was also mainly Russian and Jewish.

So when the Bolshevik propaganda called for expropriation of the bourgeoisie, the exploiters and the speculators, it was a small jump to blame and attack the Jews as such, regardless of the class they actually belonged to. They were seen as the local representatives of the bourgeois enemy against whom revenge could be taken directly. McGeever suggests there was a conception of Jews as an “ethno-class”.

But even in Petrograd, street agitators were heard calling for workers to “Smash the Jews and the bourgeoisie!”. After the storming of the Winter Palace in October 1917, some graffiti read “Down with the Jew Kerensky! Long live Trotsky!” Kerensky, the head of the deposed Provisional Government, was not Jewish, and Trotsky, the leading Bolshevik, was. But for the graffiti artist, the ‘bad guy’ had to be the Jewish one! Trotsky, as leader of the Red Army, freely admitted that his Jewishness was a propaganda advantage for the Whites in the civil war.

Red Pogroms

Dealing with the first half of 1918, McGeever gives example after example of Red Guard detachments in towns and cities all over Russia and the Ukraine indulging in antisemitic violence and looting, in which dozens of Jews were killed. But the worst atrocities from this period took place in Chernihiv Province in northern Ukraine, and especially in the town of Hlukhiv.

Having taken the town from the Ukrainian nationalist Baturinskii Regiment, in March, the main slogan of the Russian and Ukrainian Roslavl’skie Red Partisans was “eliminate the bourgeoisie and the Yids!” The bulk of the Baturinskii regiment changed sides, and together they went door to door looking for Jews who were then lined up and shot. At least 100 Jews were killed, probably many more, including schoolboys and rabbis. Synagogues were destroyed and despoiled. Soviet power was thus secured by and through antisemitism.

At this time, the new Soviet state was facing major military reversals in the civil war, so even when the news finally reached Moscow, it is easy to see why the official press described the taking of Hlukhiv as a glorious victory, while not mentioning the pogroms at all. It was part of a propaganda war. Only the Jewish press reported it.

Throughout this period, no specific work or propaganda against antisemitism was undertaken by the official state organisations or state press; it was not even discussed by the national government (Sovnarkom) between October 1917 and the spring of 1918.

Non-Bolshevik Jewish socialists

Responsibility for raising the issue, and working out practical measures that the state could and should take, fell on a committee of mainly Jewish activists, who were mostly outside the Bolshevik party. This was early after the October revolution, before the clampdown on other left parties in the summer of 1918, and non-Bolshevik socialists still freely worked inside the soviets.

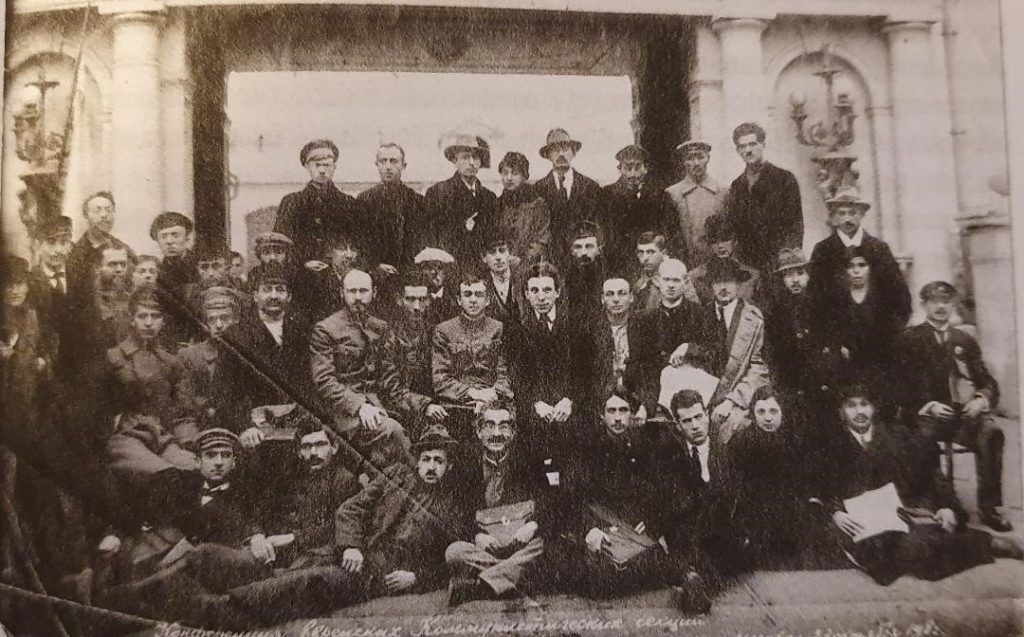

and Commissariats – Moscow October 1918.

(YIVO Institute for Jewish Research , New York)

The ongoing role of these Jewish socialists is a major theme of McGeever’s book. In January 1918 the Bolsheviks established a central Commissariat for Jewish National Affairs (known as Central Evkom) under Semon Dimanshtein, a Bolshevik since 1904. Its task was to take the Bolshevik message into the Yiddish-speaking working-class community, and also to win Jewish workers away from rival Jewish-socialist groups such as the Bund, which had split with the Bolsheviks back in 1903 over the issue of Jewish autonomous national organising. It was not founded to oppose antisemitism as such.

The problem, however, was that the Bolsheviks had very little influence or organic relationship with Yiddish-speaking workers, so they ended up having to rely on non-Bolsheviks to carry out the work. Although many Bolshevik leaders were Jewish, they were often secular intellectual, atheist internationalists. For Trotsky and most of the other Jewish Bolshevik leaders, their Jewish identity was entirely peripheral. They opposed antisemitism as Czarist reaction, but they were not intimately linked with the Jewish communities that suffered most from it, or physically fought back against it in Jewish self-defence forces, which were organised by Jewish left parties.

Moscow Evkom

The Moscow Jewish Commissariat (Moscow Evkom), which did the first systematic work to try to get the new soviet state to seriously tackle antisemitism, did not have any Bolsheviks in it! The leading personalities were Zvi Fridliand, Il’ia Dobkovskii and David Davidovich. Fridliand was leader of the left faction of the Poalei Zion a socialist-Zionist party which was split around the issue of the October revolution, which Fridliand and his faction supported and participated in. Dobkovskii was a Left Socialist Revolutionary (Left S-R). Davidovich was a member of the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party.

They battled away to pressure the leading soviet government bodies to take the problem seriously, especially following the Hlukhiv massacre, even begging Lenin himself, but from April to July 1918 no national action was taken. In Moscow, however, the regional government instructed all local soviets to discuss antisemitism, articles started to appear in the Moscow press and educational work on the issue was carried out in Red Army units.

But their work fell foul of disputes between the Bolsheviks and the other left parties, such as their coalition partners the Left S-Rs, who were strong in the Moscow Soviet (Moscow Sovnarkom). The Bolsheviks shut it down and the Moscow Evkom was shut down with it. By July, after the assassination attempt on Lenin, the coalition with the Left S-Rs came to an end, and non-Bolsheviks were no longer welcome. Fridliand and others were removed from their posts and their work was halted.

In July 1918, the national government (Central Sovnarkom) finally passed a decree on antisemitism, with instructions to “take uncompromising measures to tear the antisemitic movement out by the roots. Pogromists and pogrom agitators are to be placed outside the law” (effectively a death sentence). Sadly, by this time, most of the relevant areas affected by the pogroms had already been lost by the Red Army.

A matter of life or death

Throughout the spring the Bolsheviks thought that Petrograd would be taken, and the Reds were losing ground all over the country, and faced defeat. For the leading Bolsheviks, therefore, antisemitism was just one of many problems competing for attention. For the Jewish left parties, it was, literally, a matter of life or death. They had no alternative but to prioritise it, and physically defend their lives and those of their families.

The Jewish left parties were themselves divided over the extent to which they supported soviet power and the Reds, but especially after the German revolution of November 1918, the hope of a successful revolution and the building of a socialist society inspired Jewish socialists.

In February 1919 the Bund, which had a position of Jewish national and cultural autonomy inside Russia, split, with the left forming the Communist Bund (Kombund). It took part in government bodies and figures such as Moishe Rafes, Abram Kheifets and David Lipets played leading roles in the soviet campaign against antisemitism.

The United Jewish Socialist Workers Party (the Fareynikte) split in February 1919, with the left eventually merging with the Kombund to form the Jewish Communist Alliance (Komfarband) in May 1919. In August, their members were allowed to join the Bolsheviks as individuals, crucially recruiting into the party Jewish socialists with real roots among Jewish workers and the Jewish community in general. Even the Zionists of Poalei Zion, though still formally committed to a future in Palestine, were inspired by the possibility of building socialism “here and now” in Russia. In August 1919, they split, with the left, including Fridliand, forming the Jewish Communist Party (Poalei Zion).

Only hope

This move among Jewish parties, and Jewish people in general, to support of the Reds was greatly influenced by the huge escalation of antisemitic violence from the Whites and nationalists in 1919. Although well aware of the antisemitism within the Red Army, they knew that it was their only hope against the monstrous antisemitism of the reactionary White generals. One Red Army company consisted entirely of Jewish soldiers, some of whom sported traditional ear locks.

In 1919 the Reds started to retake the Ukraine, but to do so they had to rely on recruiting widely among the mass of the peasantry, who had turned against the Whites because they only promised a return to Czarism. These troops supported the Bolsheviks (ie the revolution and the local soviets) but were not keen on the new Communists (ie the new soviet regime) which they saw as full of Jews, and which was seizing their grain, and trying to establish more central bureaucratic control over their local soviets by Commissars. Moreover, during a desperate civil war, whole regiments led by independent warlords changed sides and flooded into the Red Army. Soviet power in the Ukraine was completely dependent on such elements.

One army, 13-16,000 strong, led by Nikifor Grigor’ev, defected from Petliura’s Ukrainian nationalist army, which had been guilty of thousands of Jewish deaths. Under the Red banner, they took Odessa on the Black Sea, to the delight of the Soviet leaders, but then adopted the slogan “long live soviet power, down with the communists, all communists are Yids!” They could thus move from ‘socialist internationalism’ to savage antisemitism in the same breath. In fifty-two pogroms over eighteen days in May 1919, they killed 3,400 Jews. In Elisavetgrad, they murdered 1,526 and hundreds more were killed over the spring and summer.

In Uman’ the 8th Ukrainian Soviet Regiment carried out several waves of progroms between March and May, killing 150. Their replacements also engaged in pogroms. Only the International 4th Soviet Regiment, made up of Jewish, Chinese, Hungarian, German and Austrian troops finally put an end to the slaughter.

At least in 1919, the Soviet government addressed the problem with the necessary seriousness. Clear decrees and proclamations were issued. Lenin’s speech from March 1919 “On the pogromist persecution of the Jews” was put on a gramophone record and played at meetings around the country. Where possible, severe penalties, including death, were enacted against progromists.

Shifting loyalties

McGeever outlines the confused picture of shifting loyalties as some regiments were sent in to deal with the antisemitic regiments, only to join in, while other regiments did their best to stop the attacks. Reports regularly came in of local soviets and Bolshevik local organisations which ignored or softened the punishments and were themselves openly antisemitic, persecuting Jewish members and debating whether to exclude Jews entirely. The truth was that in many areas, the central government simply had no force to impose its authority, and its local power often rested with antisemitic local officials and structures.

From the summer of 1919, the members of the separate Jewish socialist left parties were being incorporated into the official national structures and eventually the Communist Party itself. Organising through the Jewish Sections of the Russian Communist Party (the Evsektsiia) they played a central role once more in prompting and pressuring government from the inside and initiating public education campaigns, newspaper articles, leaflets and brochures on antisemitism, although for propaganda reasons the official Soviet press always ignored or played down antisemitic attacks by local Bolsheviks or Red Army units

While their main focus – the Committee for the Struggle against Antisemitism – was shut down in late 1919 after only a few weeks, the Evsektsiia continued to play the leading role in tackling antisemitism for the rest of the war. It continued in this role, and in promoting Yiddish/Jewish language and culture, throughout the 1920s, until it was finally closed by Stalin in 1930.

Internal controversies

There were internal controversies. Some in the party, including Lenin, and even in Evsektsiia itself, took the view that in order to take the sting out of antisemitism you should actually reduce the number of Jewish members in administrative or party positions or in petit-bourgeois occupations and send more into the army front line or to work with peasants. This sailed very close to reinforcing or conceding to exactly the same stereotypes that led to antisemitic prejudice.

Were Evsektsiia members just workers and communists who happened to be Jewish and for whom class struggle should be the main focus? Or was their Jewishness and the struggle against the oppression of all Jews integral to their struggle as communists? Did they have a special responsibility to take the lead against antisemitism, even within the party, or was that the job of communists as a whole? These are arguments that prefigure ones that continue today, regarding the degree and the purpose of self-organisation of oppressed groups such as women, or black and Asian people, LGBT+ people etc, in socialist parties and trade unions.

The lesson that McGeever draws, with which I broadly agree, is that in time of revolution and war the Bolsheviks had to rely on socialist groups that were specifically Jewish, with a commitment to some level of national/cultural autonomy, to make any inroads into the Jewish community or to push the party into dealing properly with antisemitism.

Had they previously set up specifically Jewish party structures or not broken so decisively with groups like the Bund, in my opinion, the Bolsheviks would have been stronger. Oppressed groups cannot automatically rely on others to support them or defend their interests. They need to organise themselves but also to fight for their place in the socialist and labour movement as a whole on the basis of solidarity and common struggle against an oppressive class society.

In “Red Cavalry” Babel expressed how he felt as a Jewish intellectual who came into contact with Ukrainian peasants for the first time, just as these Cossacks had not come across Jews who supported them against the landlords before. Babel described how Cossacks fought on both sides, often against each other. This was what civil war meant. I would be interested to see McGeever has to say about the policy of Bund members during the revolution. Their policy of exclusivity cemented the distance between Jews and other groups that Babel viewed as being dangerous to Jewish safety. And the Bund aligned themselves with the Mensheviks so there was no chance of Lenin forming any sort of block with them. Lenin soon after said that any member of the Ukrainian party who uses the word “yid” should be expelled immediately, which gives an idea of the scale of the problem in the early 1920s. Great Russian chauvinism was a problem in the Caucasus and on the part of party officials sent to Central Asia. Stalinism totally misrepresented this history. There is far, far more still to recover.

The Bund split during the revolution and civil war, as the book outlines, with the left forming the “Communist Bund”. They did side with the Mensheviks in 1903 and after, but the Bolshevik /Menshevik split was not so final actually onthe ground in Russia. Even Trotsky was formally a Menshevik for a while after 1903. Complete cutural separation of workers parties on national, or ethnic lines was, and is, a danger of course. That is why efforts needed to be made to make the split less decisive and permanent.

There is a good essay on Bolsheviks in Central Asia somewhere, it describes their initial mistakes, the correction made, to respect and work through their traditional institutions which won a mass base for Soviet power, and Stalin’s ultimate chauvinism through the 1930s which alienated the Muslim masses, meaning that Stalin’s rule could only be maintained by terror.

“Red Cavalry” by Issac Babel describes anti Jewish violence by Cossacks fighting Polish intervention. They brought all their prejudices with them and were fighting basically for land and that was it. Babel was the Commissar and was the only Bolshevik in the company. All he had was Pravda (which he read to the illiterate Cossacks) and the power of persuasion. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/130080.Red_Cavalry

Yeah. Babel is mentioned as a witness a few times in McGeever’s book.