By Dave Cartwright

10 years ago on 20 October 2011, Muammar Gaddafi was captured in his home town of Sirte in northern Libya fleeing from Misrata-based militia and NATO air attacks and he died that day from a gunshot wound. Thus ended the life of the man who had ruled Libya for 42 years, but 10 years on the plight of the majority of the population is immeasurably worse.

The movement against Gaddafi took place alongside the “Arab Spring” that swept through most Arab countries in 2011. The Arab Spring was a popular uprising against the terrible conditions people were facing in the Arab world: high unemployment, price inflation, poor living conditions, corruption and lack of political freedoms. In most of these countries, the leaders had been in power for decades allowing no challenge to their rule. Libya was no exception.

Arab Spring erupts

The Arab Spring started in Tunisia. Mohamed Bouazizi was a poor but popular street seller who had been harassed for years by the police as he tried to scrape a living selling on the street. On 17 December 2020 he had his weighing scales confiscated and the governor’s office refused to return them. This was the last straw. He set himself on fire and died later that month in hospital.

Protests in the city of Al-Bayda in eastern Libya, July 2011

Pent up anger over the poor living conditions and the lack of democracy in Tunisia was released and led to an uprising which has become known as the Tunisian Revolution. Long-time president Zine Ben Ali was deposed on 14 January 2011 and the beginnings of a democratic system in the form of a Constituent Assembly was established for the first time since independence in 1956.

Emboldened by the success of the Tunisian Revolution, there was an uprising in Egypt against the rule of Hosni Mubarak. Egypt had been under a state of emergency almost continuously since the 1967 war with Israel and the security services were notorious for their corruption and brutality. Mubarak resigned on 11 February 2011.

At the same time in Yemen, faced with opposition protests and mass defections from the military, Alin Abdullah Sela announced he would not seek to be re-elected President in 2013. After many failed attempts at forming a new government. Saleh signed a power transfer deal in November to stand down earlier in February 2012, as long as he was left immune from prosecution. During his reign he amassed personal wealth of $2 billion per year, a massive proportion of the annual GDP of $11.5 billion (according to a UN Security Council report).

Western military intervention in Libya

Muammar Gaddafi was determined not to go so easily. When the uprisings started against his rule in February he declared his intention to deal firmly with rebel forces. Early in the conflict the army opened fire on a demonstration in Benghazi and hundreds were killed. The opposition grew and by the end of February many of the eastern cities like Benghazi and Misrata were in rebel hands. Opposition leaders formed a National Transitional Council in February, combining various rebel groups.

Gaddafi had been a thorn in the side of western powers for the whole of his time as leader in Libya, since he came to power in 1969, immediately putting the government in firm control of what was then a massively increasing oil economy. For western governments he was always a ‘rogue’ ruler, giving dispensing his financial backing to radical opposition movements around the world. Libyan agents were involved in the bringing down of the passenger airline over Lockerbie in Scotland. In London, a service woman police officer on duty was shot and killed by a gunman firing from the Libyan embassy.

By National Defense University – 110328_POTUS_Libya_NDU_073 (direct link), CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14974529

Here was their opportunity, in 2011, to get rid of him. In February, the UN Security Council passed a resolution to freeze the assets of Gaddafi, but his forces managed to retake some of eastern cities like Benghazi. In March, the UN passed a resolution calling for a ceasefire, declaring a no-fly zone and defending military strikes to ‘defend citizens’. Two days later military intervention began.

The British and American navies fired Tomahawk cruise missiles and Canadian and French forces joined in to provide a naval blockade and destroy tanks. Instead of letting the people of Libya make the social changes they needed themselves, the western powers used their military might to control the progress of the civil war that had developed. Months of conflict continued and a decisive break occurred when rebels backed by NATO bombing took the capital Tripoli in August. Gaddafi and his closest associates escaped to Sirte where they were eventually tracked down on October 20 and Gadaffi was killed by an unknown militiaman.

Libya 10 years on

Tunisia is the only country to have maintained even the semblance of a democratic system after the Arab Spring. Libya’s progress started badly and has gone from one crisis to another. In 2012, the first elected prime minister lasted just one month and there were seven different prime ministers in the first four years. Rival factions, often tribal-based, failed to agree on a stable government. In October 2013 secessionists in the eastern part of Libya, where most of the oil resources are located, declared their own government. Ali Zeidan, the prime minister was captured and held hostage.

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-19744533

Elections in June 2014 to a new House of Representatives (to replace the GNC, the General National Council) were marred by violence. Only 1.5 million voters were registered to vote compared to 2.8 million in 2012, some polling stations were attacked and so they closed for security reasons. Less than half of the eligible population voted.

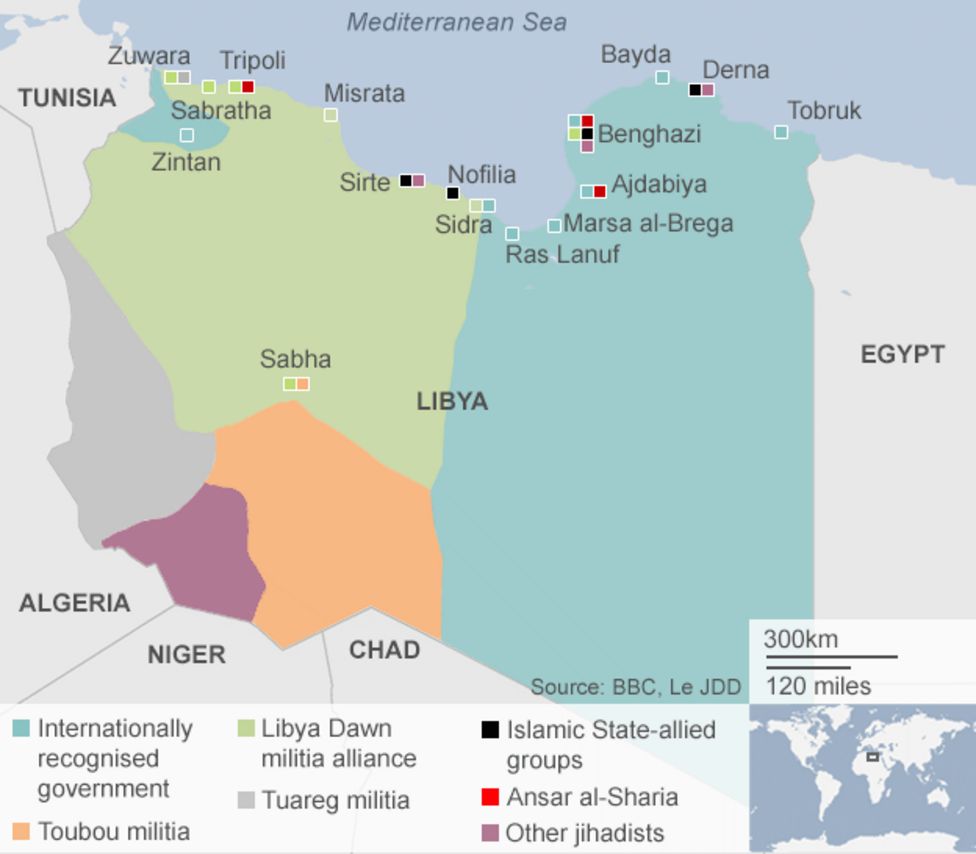

The 2014 election showed lower support for Islamist factions who refused to accept the result and declared that they would maintain the GNC in which they had more members. In July 2014, an Islamist militia from Misrati attacked the capital, Tripoli and six weeks later in the name of the Libya Dawn grouping, declared a government they called ‘a national salvation government’. In October the House of Representatives, led by the secular Operation Dignity coalition moved to the eastern city of Tobruk and declared themselves the Government. So Libya had two warring governments with limited control over many parts of Libya. This left a vacuum rife for the operation of local warlords.

The plight of Libya’s population is immeasurably worse

Since the intervention of the major capitalist states to ‘rescue’ Libyans from Gadaffi, the plight of the majority of the population has become immeasurably worse. Gadaffi’s regime was a bloody dictatorship that brooked no opposition or democratic freedoms. But at least a portion of the national oil wealth filtered its way down to the benefit of sections of the population.

Today, there is not even that. Libya, thanks to US, British, French and other state interventions, is a failed state, beset by warring militias, death and destruction. Not surprisingly, many young Libyans have been forced to seek opportunity and personal safety elsewhere, even at the risk of a perilous dinghy crossing across the Mediterranean.

Libya is a warning, if ever one was needed, that capitalist states do not intervene in other states for the benefit of the local population, but in the hope of sponsoring their own power, prestige and economic interests.

Regional instability

Gadaffi had suppressed radical Islamist groups. They were amongst the rebel forces fighting against him and after Gadaffi fell they refused to give up their arms and started to build a base. Libya became a haven for terrorist groups. According to a BBC report in 2015 there were nearly 2,000 militias operating around the country and there were active groups like the so-called Islamic State (IS) and Ansar al-Sharia (Al-Qaeda’s Libya affiliate).

And there was an impact on neighbouring countries as well. After the fall of Gaddafi, the ethnic Tuaregs in his army returned to Mali taking their weapons with them. They began a rebellion of their own in northern Mali which was taken over by Islamist groups who declared an independent Islamic state in that area renaming it Azawad. The Mali government regained control of the area in 2013 with the help of forces from France and some of the African Union states, but sporadic fighting continues to this day.

The continuing instability in Libya has a knock-on effect in other neighbouring countries besides Mali such as Chad, Burkina Faso and Niger which already had internal tensions. The foreign ministers of Egypt, Tunisia and other countries are calling for all overseas mercenaries to leave Libya but have fears about the effect on these countries.

The world’s most dangerous migration route

When he was in power, Gadaffi regulated the movement of refugees through Libya and used his control to gain concessions from the EU and Italy. But once he fell, “the smuggling economy [was able] to expand its capacity and logistical latitude, and operate with greater impunity than ever before”, according to a 2018 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Libya became the main conduit for refugees seeking to leave Africa and go to Europe.

The central Mediterranean route from Libya to Italy is highly dangerous for refugees

Photo by Vito Manzari licensed under CC BY 2.0

A recent article in the Financial Times describes the experiences of Precious who tried to get from Nigeria to Italy, a route which the International Rescue Committee describes as “the world’s most dangerous migration route.” She was passed from middleman to middleman. She was beaten and starved. When she arrived in Libya she was held for a year in forced prostitution with dozens of other women until she managed to escape back to Nigeria.

Crossing the Mediterranean via the central route from Libya to Italy is a dangerous route. Figures from the International Organisation for Migration for 2015 showed that 2,889 died making the attempt that year, nearly 2% of the total.

The International Rescue Committee estimates that 700,000 refugees are currently stranded in Libya. Many of them are hired out as slave labour.

Collapse in living standards

With large oil reserves, Gaddafi benefited from the oil bonanza of the 1980s. Although he and his family syphoned off a signifiant proportion of the country’s wealth for themselves ($200 billion according to a 2011 article by the Los Angeles Times), the living standards of the population could be raised. Already in the 1970s the average wage of a young semi-skilled worker was £300 a month whereas their Egyptian counterpart earned just £30 (according to Peter Mansfield in his book, The Arabs).

Oil production in Libya 1980 to 2017

Source:

https://www.worldometers.info/oil/libya-oil/

Oil production stopped completely in the 2011 war. There was a recovery in 2013 but the continued instability in the country has meant oil production now barely reaches a quarter of the 2010 level. Although Libya is ranked 9th in the world for all reserves, it is currently only ranked 30th for oil production.

Libya’s main source of income is now massively reduced and the ongoing instability in the country causes disruption in all areas of economic activity.

Ten years after the death of Gaddafi the people of Libya are living in a country torn apart by internal conflict, where terrorist groups and people traffickers are able to operate and where basic living conditions are harsh. The early hopes from the Arab Spring have evaporated. Instead a new hope needs to be found in Libya and the whole region, one based on socialism and workers democracy.