By John Pickard

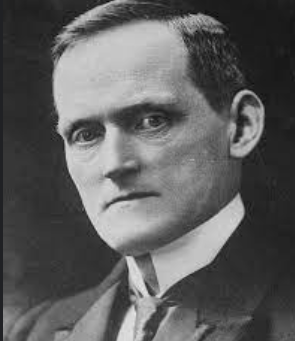

Ninety years ago this week, a general election confirmed a ‘National Government’ in office, under the premiership of Ramsay McDonald, former leader of the Labour Party. The government elected was in all but name a Tory government, the Conservatives having won 518 MPs out of 554 ‘National’ MPs. The few former Labour ministers left in office were a smokescreen for a harsh austerity government.

The story behind the formation of the National Government began in 1929, with the election of the second minority Labour government, which from the beginning was caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, although it had the largest number of MPs, it was in an overall minority and depended on the Liberals to pass any legislation. Any reforms it wanted to put through parliament also had to get past a hostile House of Lords, tipped in favour of the interests of capitalism.

But on the other hand, the Labour Party and the trade union rank and file had worked hard for a Labour government. After having suffered the defeat of the General Strike three years before, many workers had pinned their hopes on the political wing of the movement to deliver meaningful improvements in their lives. Labour got over eight million votes, a record up to that point.

Overwhelmingly hostile press

From the beginning, what reforms the Labour administration was trying to carry through – and it attempted at first to make some changes – were blocked, delayed or in some other way stymied by the combined efforts of an overwhelmingly hostile press, the House of Lords, and the mandarins of the Civil Service, whose loyalties lay with capitalism, not with the government of the day. Not to mention the Liberals and Tories in the Commons.

The government’s attempts to introduce a seven and a half hour working day in the mines, for example, were sabotaged by the mine-owners themselves and without any system of policing new regulations, the Coal Mines Act was widely flouted by the coal barons. A bill to empower local authorities to utilise land for much-needed house-building was savagely mauled in the House of Lords and by civil servants in the Treasury, until it ended as a pale shadow of the intended law.

The Labour government was beset by catastrophic economic problems almost as soon as it took office. In September and October 1929, Wall Street tanked, and the knock-on effect in capitalist economies around the world ushered in what was to become a period of deep depression. Within a year, 2.3 million were unemployed in Britain and the numbers kept on rising. It was to reach 2.7m by the summer of 1931, when the government crisis came to a head.

Mushrooming expenditure on unemployment benefit

The government initially made attempts to improve welfare benefits for the unemployed and to make them easier to access, but it had to go repeatedly to parliament to approve the mushrooming expenditure on unemployment benefit. In this fraught economic climate, the pressure from the capitalist class began to build up to a crescendo, as big business, the Tories in parliament, the national press and Treasury civil servants began to demand ‘economies’, in other words cuts in welfare, to ‘balance the books’ – a message we have heard a hundred times since then.

There were calls in meetings of business leaders for the Government and local authorities “to cease from all expenditure which is not absolutely necessary”. The level of taxation was described as “the heaviest in the world” and there were demands that “something be done” to cut government expenditure, which was “a national danger”. (The Times, January 28, 1931)

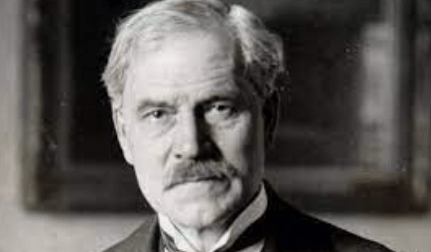

Philip Snowden, the Labour Chancellor, was extremely receptive to all this pressure because his entire political and economic outlook was based on capitalism. Even more than previous Tory Chancellors, he was an advocate of strict economic orthodoxy. In January 1931, he told the Cabinet that the budget prospect for the year “is a grim one,” and that the government deficit was going to go up as high as £70m – a huge figure for the time – and that it was untenable in the longer term.

Snowden reflected the consensus of capitalism

The core of Snowden’s message to the Cabinet was that “this country cannot afford a Budget with any sort of deficit” and he complained that international financial dealers were “losing confidence in London.” As one study of the period (Bill Janeway) noted, “Snowden was reflecting the consensus of City and industrial opinion. ‘Retrenchment’ in expenditure had become the common theme of both the Conservative and Liberal oppositions…”

By this time, the government had all but abandoned any attempt to pass reforming legislation, having been defeated on a number of measures by the Lords and the combined opposition of Liberal and Tory MPs. Indeed, the government was already being forced along the road of counter-reforms, as measures were pushed through to economise on welfare by cutting the benefits payable to short-time, casual and seasonal workers, and limiting the right of married women to claim.

At the very end of July, the May Committee, established under Liberal pressure some months before, to look at the looming government deficit, brought out its recommendations. These were for swingeing cuts in public expenditure, with the heaviest burden falling on the unemployed and working people. The Committee proposed a cut in government expenditure of around £97m. Although it was proposed that there would have to be cuts in wages for all public sector employees – including the police and armed forces – nearly seventy per cent of the savings were aimed at unemployment benefit.

By this time, Janeway writes, “the Bank of England was actively focused on pressurising the government to implement the May proposals…The Bank even rejected offers from the French authorities of credits and market collaboration in defence of sterling as they “might easily be counter-productive in postponing the solution—measures to balance the budget and reduce costs” (Williamson, 1986, p. 200).”

Surrender to the pressure of capitalism

The downfall of the Labour government in August 1931, therefore, came from an accumulation of effects, each one of which was a surrender to the pressures of capitalism. The first in December 1930, was the appointment of a Royal Commission on unemployment benefit, tasked with devising a system that “solvent and self-supporting“. Then in February 1931, the May Committee was set up. Lastly, when the May committee reported, it was pressure from the capitalist press, the Liberals and Tories and not least the Bank of England, to implement the May proposals.

The Macdonald cabinet met virtually continuously to find a way to implement the proposed cuts, but the rank and file of the labour movement were adamantly opposed and this was transmitted through a section – a minority – of Labour ministers. The government was in an impasse.

According to Sydney Webb, a leading Fabian at the time, “the King, with whom the Prime Minister had been in constant communication…made a strong appeal to him to stand by the nation in this financial crisis and to seek the support of leading members of the Conservative and Liberal parties in forming, in conjunction with such members of his own party as would come in, a united National Government.” (What happened in 1931 by Sydney Webb)

With a cabinet minority threatening to resign, therefore, and on the advice of the King, McDonald resigned – without speaking to the majority of ministers, or the Parliamentary Party, let alone the Labour Party as a whole – and announced that he was forming a ‘National’ government with the support of Liberals and Tories. His new cabinet included four former Labour ministers, McDonald, Philip Snowden, JH Thomas and Lord Sankey, as well as four Tories and two Liberals.

General election to ratify formation of National Government

When the National government was formed, McDonald immediately began to implement the May proposals, to the outrage of the Labour Party and trade union movement. It was later, after the damage was largely done, that McDonald called a general election to ‘ratify’ his previous decisions.

Once the Labour Party recovered from the immediate shock, McDonald was expelled from the Labour Party and disowned by his Constituency Labour Party in Seaham, a mining area in County Durham. Arthur Henderson was elected party leader, in those days exclusively by Labour MPs. “All but about 5 per cent of the Labour members and all but about 4% of the chosen Labour candidates steadfastly adhered to Mr Henderson who was elected leader of the Party.” (Sydney Webb)

In the ensuing general election, the national press overwhelmingly supported the election of a National Government. Although the Labour Party was hammered in terms of the number of MPs elected – only 52 – its overall vote was still 6.3 million, over 30% of the total, and it was able to recover in subsequent years.

The betrayal of Ramsay McDonald – and it was seen by the labour movement as a betrayal as it has echoed down the generations to this day – had a dramatic effect on the political mettle of those who remained in the party to fight on. To begin with, the party moved dramatically to the left. It was a scenario already anticipated by the strategists of capitalism.

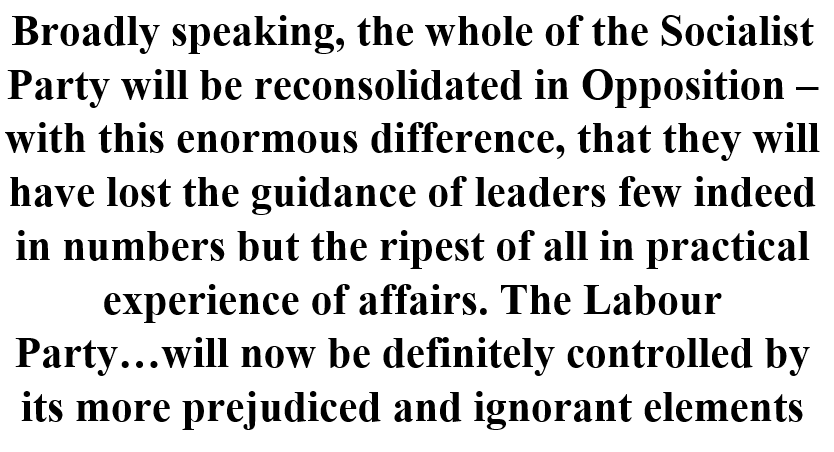

“Broadly speaking,” a haughty editorial in The Times said on August 26, “the whole of the Socialist Party will be reconsolidated in Opposition – with this enormous difference, that they will have lost the guidance of leaders few indeed in numbers but the ripest of all in practical experience of affairs. The Labour Party…will now be definitely controlled by its more prejudiced and ignorant elements.”

1934 Labour Programme firmly on the left

And so it proved. Leaders like Lansbury, Cripps and Attlee came to the fore precisely because they articulated the most left-wing and radical ideas, popular with the rank and file. The 1934 Party programme, Socialism and Peace, explicitly stated that “what the nation now requires is not merely social reform, but Socialism.” It pledged a future Labour government to “public ownership and control of the primary industries and services as a foundation step.”

To be sure, the right wing hadn’t disappeared. The new leader, Arthur Henderson, had even explicitly supported the idea of a National Government, but would have preferred to have the decision to form one taken to a special Labour conference. It wasn’t so much McDonald’s betrayal he objected to as the manner in which it was done. He and other right wingers stayed in the Party, and no doubt would have been prepared to ‘do a McDonald’ if it was required to save capitalism at a later date.

As for the left, it grew enormously in authority and strength. The Independent Labour Party, which was an integral part of the Labour Party and its most consistently left-wing core, increased its support to something like 100,000 members. The ILP could have been the arena for the formation of a mass movement of Marxist in British politics for the first time, as many of its members were moving in a revolutionary direction, far ahead of its leaders.

But unfortunately, sectarianism and short-sightedness are not modern features of the left. The Independent Labour Party, broke away from Labour, as Trotsky noted later, at the wrong time and for the wrong reasons. It was not a split over an important political principle, but over the question of ‘discipline’ in the Parliamentary Labour Party and how it applied to ILP members.

Having split, the ILP quickly decreased in size and influence until it was largely an irrelevance to the labour movement. Had the ILP stayed, the entire subsequent history of Labour might have been different.

Aspirations of millions of workers

What are the lessons of the 1931 betrayal? As we have argued, there have always been two opposing class pressures at work in the Labour Party. While the grass roots reflect the aspirations of millions of affiliated trade union members and Labour voters, those at the ‘sharp end’ of the economic crisis, the leadership and most of the PLP are political mouthpieces of the capitalist class.

These two opposing class forces play out in the Labour Party with different degrees of intensity at different times. Essentially, the sharper the class struggles in society at large, the sharper the differences are reflected inside the Labour Party itself.

The question of a split in the modern Labour Party, therefore, is not one of principle, but of timing and circumstance. It does not look like there will be a major split in the Labour Party in the immediate future, despite growing divisions between the rank and file (especially the unions) and the leadership. In the event of Labour being elected into office, however, it is likely that those divisions will intensify.

As it was in 1929, the grassroots of the Party – those who do the election graft and get MPs elected – will expect ‘their’ government to implement meaningful reforms. But where the majority of ‘Labour’ MPs put their faith in the capitalist free market, economic pressures will force them in the opposite direction. The more intense the economic crisis, the greater will be the possibility of a new split in the Party and another National Government.

Keir Starmer has given Johnson a ‘pass’ on key issues

History never repeats itself exactly, of course. But we already see today that right-wing Labour MPs – those who speak about ‘Britain’ and the ‘national interest’ as if classes did not exist – are already half way to agreeing a ‘cross-party’ consensus on ‘what needs to be done’. Keir Starmer has given Boris Johnson a ‘pass’ on key anti-democratic measures like that ‘Spy Cops bill’ and other measures. His opposition to the Tories’ Covid strategy has been lukewarm at best. He has draped the Union Jack around his press conferences as much as any Tory leader.

We would have to say, therefore, that in general terms, some kind of ‘national’ government would be inherent in the almost certain event of a Labour government facing a deep crisis in the capitalist economy. The same pressures would be there, demanding policies in the ‘national interest’: the press, the courts, the House of Lords, the tops of the Civil Service and the Bank of England. As it was in 1931, the monarchy would also be available to play an auxiliary role in the ‘national’ interest.

There is an alternative path that a socialist Labour government could follow. It could mobilise opinion through the organised labour movement, seek the active support of trade union members in the banks, in the media and TV, as well as throughout the country and use their support to implement measures that challenge the capitalist system itself.

It would use the economic crisis as an opportunity and a justification for fundamental change. If the system cannot afford to maintain workers’ living standards, then it is the system that must go – that would be the message of a socialist leadership.

Unfortunately, as it was in 1931, the majority of ‘Labour’ MPs would be unwilling to follow such a course. Activists in the labour movement, therefore, should discuss the events of 1931, not only for its historical interest, but more to prepare themselves for events that might unfold in the future.