By Michael Roberts

The Chinese Communist party’s central committee recently held its sixth plenum, to discuss “the major achievements and historical experience” of the party in its 100-year-history, as well as to consider policy “for the future.”

Just after this, Jamie Dimon, the JPMorgan Chase chief executive, joked that the Wall Street Bank would outlast the Chinese Communist party. “I made a joke the other day that the Communist party is celebrating its 100th year. So is JPMorgan. I’ll make a bet that we last longer,” he said, speaking at the Boston College Chief Executives Club, a business forum.

What is the experience and future for China and its Communist party rule? It seems appropriate to consider a number of new books on China that have been published that try to answer this question.

Let us start with Isabelle Weber’s, How China escaped shock therapy. This has had a wide and significant impact in academic leftist circles, endorsed as it is by Branco Milanovic, the leading global inequality expert and also author of a recent book, Capitalism Alone, in which he argues that socialism can never happen and the choice for human social organisation for the foreseeable future is between ‘liberal democratic’ capitalism (the US and the ‘West’) or ‘political capitalism’ of an autocratic state (China, Russia).

Restoring capitalism through ‘shock’

Weber’s book is an account of how and why China did not go down the road of restoring capitalism through the ‘shock therapy’ of privatisation and the dismantling of state control as Russia did in the early 1990s. Instead, according to Weber, China’s leaders under Deng in the late 1970s debated what direction to take and opted for a gradual opening-up of the planned state-owned economy to capitalism, partly through privatisation, but mainly through foreign investment.

Weber argues that the ‘gradual marketization’ of the Chinese economy facilitated China’s economic ascent but without leading to ‘wholesale assimilation’ to capitalism. The decision of the Chinese leaders for a gradual move to capitalism was anything but a foregone conclusion or a “natural” choice predetermined by Chinese exceptionalism, Weber claims. In the first decade of “reform and opening up” under Deng Xiaoping (1978– 1988), China’s mode of marketization was carved out in a fierce debate. Some argued for shock therapy-style liberalization while others preferred gradual marketization beginning at the margins of the economic system. Indeed, on at least two occasions, Deng opted for a “big bang” in price reform but stepped back from the brink.

From the 1980s, the influence of the dominance of neoclassical economics in the West, both in universities and in government, set in motion the process of China’s marketization. Those Chinese economists who favoured a gradual dual economy development were replaced by economists with neo-classical market zeal. But the neoclassical policy of allowing the market to set prices led to increased inflation and eventually the Tiananmen Square protests, the ensuing military crackdown and the imprisonment of Zhao, then General Secretary of the CCP.

Neoliberal reforms made deep in roads

Even so, according to Weber, throughout the 1990s, the economics profession in China continued to align with the international neoclassical mainstream. Neoliberal reformers made deep inroads in the arenas of ownership (selling or liquidating state enterprises), deregulating the labour market and the healthcare system (partly privatised) – things that I think have come back to haunt China’s leaders now, forcing them to advocate under Xi a new turn towards ‘common prosperity’.

However, Weber reckons that the core of the Chinese economic system was never destroyed in one big bang. Instead, it was ‘fundamentally transformed’ (?) by means of a dynamic of growth and globalization under the activist guidance of the state. In October 1992, Deng Xiaoping made the formal decision to establish a ‘Socialist Market Economy with Chinese Characteristics.’

This formulation was a hybrid concoction which Jiang Zemin, explained as “whether the emphasis was on planning or on market regulation was not the essential distinction between socialism and capitalism. This brilliant thesis has helped free us from the restrictive notion that the planned economy and the market economy belong to basically different social systems, thus bringing about a great breakthrough in our understanding of the relation between planning and market regulation.” Market socialism was born.

Under Zemin, China moved further towards a capitalist market economy. Weber says that the Chinese leadership of the 1990s “was willing to shatter all remaining boundaries to the operation of market forces, in the name of economic progress.” Controls over essential consumer and producer goods were now dismantled step-by-step. However, the impact of this “big bang” was far smaller than it would have been a few years earlier. By 1992, “the liberalization effort was akin to jumping off a low-standing rock at the base of a mountain from which one has just descended” (Weber).

From direct planning to indirect direction

Weber argues that the state maintained its control over the “commanding heights” of China’s economy as it switched from direct planning to indirect regulation through the state’s participation in the market. “China grew into global capitalism without losing control over its domestic economy.”

Weber’s book is insightful in showing the debates on policy among the CP leaders about what direction to go and the factors that dominated their thoughts. However, Weber appears to do so from the viewpoint that China was capitalist at least from the point of Deng’s leadership and all the debates after were about how far to go – whether to go for ‘shock therapy’ or moderate moves towards ‘more capitalism’.

Weber appears ambiguous on the economic foundation of the Chinese state. For her, China ‘grew into global capitalism’ but still “maintained its control over the commanding heights”. What does that mean for the future?

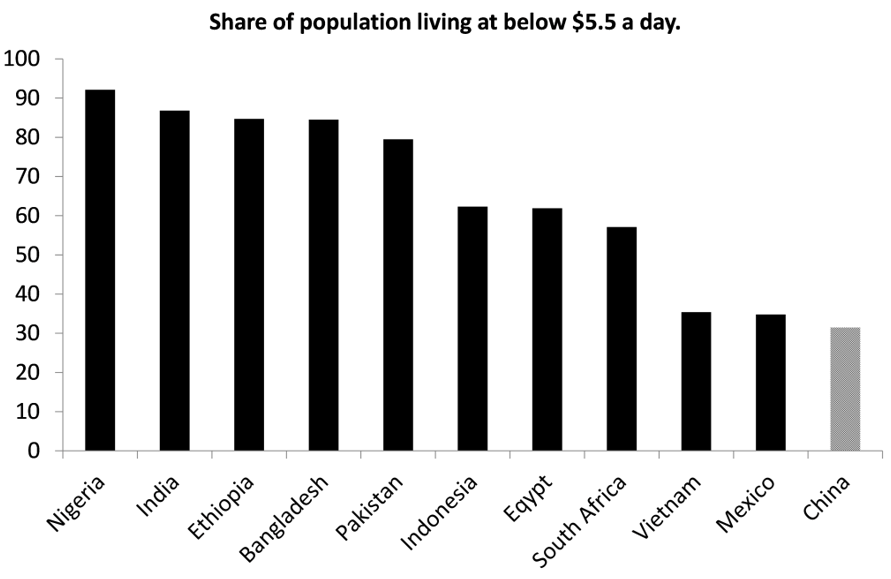

In sharp contrast, there is no ambiguity from John Ross, in his new book, China’s Great Road. Ross is Senior Fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China, and writes profusely in defence of China and its economic model as he sees it. Ross provides the reader with a wealth of data on China’s unprecedented economic success, taking over 900m out of poverty (as defined by the World Bank) and outstripping every other economy in output and wage growth over the last 30 years.

Ross’ view of the Chinese model of development, ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, is in reality a ‘radical version’ of Keynesianism. But it is different to Keynesian policies in the US and Europe, where budget deficits have been utilised, low central bank interest rates have been pursued and some forms of quantitative easing, driving down long-term interest rates through central bank purchases of debt have been applied.

“In China, in contrast, relatively limited budget deficits have been combined with low interest rates, a state-owned banking system and a huge state investment programme. While the West’s economic recovery programme has been timid, China has pursued full blooded policies of the type recognisable from Keynes General Theory as well as its own ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

State-led economic model the reason for success

Ross argues that it was Deng’s lack of ideology or commitment to either a market or state-led economic model that was the reason for China’s economic success. (Deng: “I don’t care if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.”). Ross says: “Because in the US and Europe, of course, it is held that the colour of the cat matters very much. Only the private sector coloured cat is good, the state sector coloured cat is bad. Therefore, even if the private sector cat is catching insufficient mice (ie the economy is in severe recession), the state sector cat must not be used to catch them. In China, both cats have been let loose – and therefore far more mice are caught.”

So Ross seems to accept Deng’s view that the planning mechanism and public ownership were not vital to China’s success and the market could and can do as well, if not better, in developing China’s economy. Ross asserts: “A systematic comparison of Marx’s concepts with those of the post-1929 Soviet Union makes it entirely clear that post-Deng policies in China under reform and opening up were far more in line with Marx’s than were the USSR’s”.

But is it really the case that opening up the economy to a capitalist sector and foreign investment, while necessary for China’s economic development from the 1980s, has no serious contradictions and consequences for China’s ‘socialism’? That’s not how Lenin saw it when he reluctantly opted for the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921 in Russia in order to restore agricultural production after a world war and a civil war.

For Lenin, NEP was a necessary step back in the transition to socialism forced on the Soviet Union by the wars and the failure of other revolutions in Europe. Russia was on its own. With NEP Lenin put it this way: “You will have capitalists beside you, including foreign capitalists, concessionaires and leaseholders. They will squeeze profits out of you amounting to hundreds per cent; they will enrich themselves, operating alongside of you. Let them. Meanwhile you will learn from them the business of running the economy, and only when you do that will you be able to build up a communist republic.”

Lenin’s view on the New Economic Policy

Lenin called the NEP ‘state capitalism’, not ‘socialism with any special characteristics’. China’s ‘long NEP’ as described by Weber is not a fulfilment of Marx’s teachings, as Ross claims, taking China gradually towards ‘socialism’; but in reality, it was a forced step back to capitalism.

Lenin in 1921 posed the contradiction for Russia that Ross ignores for China now: “We must face this issue squarely—who will come out on top? Either the capitalists succeed in organising first—in which case they will drive out the Communists and that will be the end of it. Or the proletarian state power, with the support of the peasantry, will prove capable of keeping a proper rein on those gentlemen, the capitalists, so as to direct capitalism along state channels and to create a capitalism that will be subordinate to the state and serve the state.”

Ross unfortunately goes close to echoing the views of that anti-socialist socialist, the recently deceased Hungarian economist Janos Kornai, widely acclaimed in mainstream economic circles. Kornai argued that China’s economic success was only possible because it abandoned central planning and state dominance and moved to capitalism. According to Kornai, democracy (undefined) can only exist under capitalism as socialism is restricted to dictatorial and autocratic forms: “democratic socialism is impossible”.

Combining public ownership of the commanding heights, indicative planning and a large capitalist sector with market prices has taken China forward, but it has also increased the contradiction between the law of value and the market and planning for social need. In my view, this is the key contradiction in all ‘transitional’ economies and also within the Chinese economy.

‘The invisible and the visible hand’

But Ross seems to argue that the combination of markets and planning as the way forward to a ‘socialist China’ has no contradictions. He quotes Xi: ‘we need to make good use of both the invisible hand and the visible hand’. China can and will, because of its economic structure, use both the ‘invisible hand’ of the market and ‘visible hand’ of the state.” But can Deng’s private sector cat and the state sector cat live together in harmony for the foreseeable future or will the contradictions inherent in this combination increase and intensify? – the current crisis in the post-COVID Chinese economy suggests the latter.

Ross recognises that “inequality in China, as is admitted domestically, has risen to levels which are excessive, and need to be corrected,” but he does not explain why there is such inequality and how it may be reduced. Yes, there have been periodic crackdowns on corrupt party functionaries and the excesses of private capitalists (Jack Ma, for example). But the Chinese leaders continue to oppose any sort of independent action by workers and strikes remain illegal, although in many cases, this prohibition is not strictly enforced.

Ross reckons China’s economic success is based on ‘socialism’ Keynesian-style: “reform and opening up, and socialism with Chinese characteristics, can be easily understood within the framework of Keynes.”, referring to Keynes concept of the ‘socialisation of investment’. “China’s economy is not being regulated via administrative means but by general macro-economic control of investment—as Keynes advocated.”

But this is a distortion of both Keynes and China. Keynes’ socialisation of investment’ never involved massive public ownership of the commanding heights of an economy – he was strongly opposed to that. And China’s economic success is based primarily on state-owned and led investment not on Keynesian ‘macro management’ of credit and fiscal measures as in capitalist economies. Ross’ explanation of China’s economic success implies that capitalist ‘macro management’ can work – when it has clearly failed in the advanced capitalist economies.

A Marxist model of China’s economy

This is not a Marxist view of China. A Marxist model of China’s economy should not start by looking at the rate of savings or investment in an economy. Marxist theory starts from the law of value. China’s success is because the law of value which operates in capitalist markets, foreign trade and investment was at first totally blocked and later controlled by a large state-owned sector, central planning and macro policy, as well as by restricted foreign ownership of new industries and controls on the flow of capital in and out of the country. The Keynesian analysis misses a key ingredient and contradiction of economic development, the productivity of labour versus the profitability of capital.

The Marxist model argues that the level of productivity will decide economic growth because it reduces the cost of production and enables a developing nation to compete in world markets. But in a capitalist economy where the law of value and markets operate, there is a contradiction: profitability.

In the Marxist model, there is a long-term inverse relationship between productivity and profitability. Profitability comes into conflict with productivity growth in a capitalist economy and so will result in regular occurrences of crises in production. A developing economy needs to restrict this conflict to a minimum.

In so far as China’s private capitalist sector increases its contribution to the overall economy and the public sector’s role is reduced, then the profitability in the overall economy becomes relatively more important and the contradiction between productivity growth and profitability intensifies. Both the neoclassical and Keynesian models of development ignore this contradiction.

Largest and most dynamic policy in the world

Richard Smith is his new book definitely does not miss the contradictions in a transitional economy with the contradictory forces of planning and the market in play. He considers China is a “bureaucratic hybrid”, neither capitalist nor a ‘command’ economy. China’s rulers preside over the largest and most dynamic economy in the world, a powerhouse of international trade whose state-owned conglomerates count among the largest companies in the world. They profit immensely from their state-owned enterprises (SOEs) market returns.

But they’re not capitalists, at least not with respect to the state-owned economy. Communist Party members don’t own individual SOEs or shares in state companies like private investors. They collectively own the state which owns most of the economy. They’re bureaucratic collectivists who run a largely state-planned economy that also produces extensively for market. But producing for the market is not the same thing as capitalism.

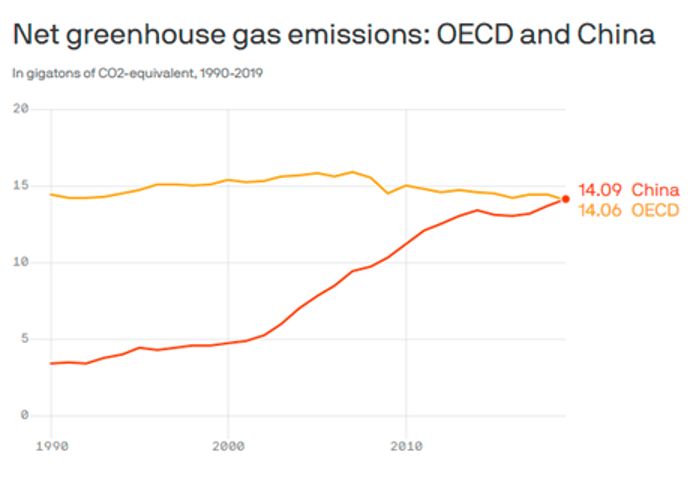

But Smith concentrates his fire on the failure of the Chinese government to handle the continued rise in carbon emissions and environmental degradation that China’s economic expansion has generated. Both capitalist and state-owned enterprises continually ignore or flout climate and ecological directives and Xi accepts this because otherwise economic growth will slow and unemployment increase and undermine Xi’s drive industrial self-sufficiency in the face of the attempts of imperialism to isolate and strangle China.

The historical polluters of the world

Smith argues that there is just no way that Xi can “peak China’s emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060” while also maximizing growth. He can “pursue development at the expense of protection” or he can “transition to green and low-carbon development… [and] take the minimum steps to protect the Earth, our shared homeland.” He can’t do both. Actually, what Smith shows is that no one country can deliver on controlling emissions and avoiding climate disaster – by definition this is a global existential threat.

The countries of the global south are not the historical polluters of the world. That honour falls to the imperialist countries that industrialised from the 19th century onwards and continue to shift the generation of emissions to the periphery by consuming the manufacturing and resource commodities produced in the likes of China, East Asia, India, Latin America and Russia.

These countries need help to reduce emissions and stop destroying nature as they seek to ‘catch up’ with the global North. That help won’t come as long as imperialism continues. Rather than coordinate with China to deal with climate change, the ‘international community’ is aiming to ‘contain’ and isolate China globally.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.