By Mike Cullen

The following is the text of a pamphlet, written by Mike Cullen, on his experiences as a docker in Liverpool.

I started work on the Liverpool docks in January 1965. I was employed by the National Dock Labour Board as a registered dockworker. They supplied dockworkers to the various stevedoring companies which serviced ships coming into Liverpool and Birkenhead.

Dock work at that time was casual labour. Dockers were put into various controls along the docks and the dockers called these ‘pens.’ I was allocated to Number 10 Control. To get work we had to report at 7.50am and 12.50pm to see if there was any work available. The foreman used to come into the control, and we knew when we were hired by getting a tap on the shoulder.

You then passed your book over, which was a record of where you had been working, depending on the type of work you were hired for: whether it was to work on a ship discharging cargo or on the quayside receiving or delivering cargo. If there was no work available in the morning you had your book stamped ‘AP’ which meant you had attended. For that shift you received 11 shillings, or 55 pence in today’s money. You received the same amount for the afternoon shift if there was no work. That meant if you had no work at all on that day, you received £1 and 2 shillings or £1.10.

If you had been hired by one of the stevedoring companies, then they would stamp your book. At the end of the working week, your book was either stamped by the control for no work or stamped by the company you had worked for. The weekly wage was paid by the stevedoring company.

1967 strike and the end of casualisation

In 1967, there was a national dock strike against casual labour and at the end of six weeks, the result was the end of casualisation and the formation of the National Dock Labour Scheme. This was the product of a report by Jack Jones, who was the General Secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU – now part of UNITE) and Lord Allington. As a result, the dock workers were no longer casual and they were allocated to one of the various stevedoring companies and were paid a weekly wage.

From 1967, with the changes in cargo handling, eg the palletisation of some cargo and the introduction of ‘roll on and roll off’ ferries, the docks required less labour. Some of the older dockers took the severance payment that was on offer. Some of the younger dockers also took the severance and went to work in Ford’s and Vauxhall’s where the money was better.

Moving into the 1970s, when containers were more and more prevalent on the docks, it was the dockers’ jobs to pack and empty the containers. That work was being moved out of the dock area, and so the London dockworkers went on strike and picketed the outside firms. Four of them were arrested and jailed. One more was arrested outside the court and the Tory government of the day, under Prime Minister Ted Heath, could see that the jailing of the five dockers, who were called the ‘Pentonville Five’ [after the prison they were in] could mean that the strike could lead to all registered ports going out, eg, Liverpool, Hull, Bristol and a few more.

The ‘Official Solicitor’ gets the Tories off the hook

So, to get themselves off the hook, the Government brought out someone called the ‘Official Solicitor’ and the five dockers were released. This was the first time in 200 years that the Official Solicitor had acted. Nobody had ever heard of him before and it was a ploy to get the government out of a fix, because it ended the strike and stopped it from spreading throughout the country.

I was employed then by a company called ‘Ocean Ports Services’ based in the Toxteth Dock in the south end of Liverpool. The company serviced the Moss ships, which sailed out of the Mediterranean ports, including Cyprus, and they carried stores and equipment for the army based in Cyprus. Due to the ongoing cargo handling and the introduction of the opening of the container terminal at Seaforth in 1971, fewer dockers were needed. So there was another offer of severance pay: many dockers accepted it.

During the 70s and 80s, there were a lot of disputes on the docks. The Liverpool dockers supported everyone who needed supporting and these included the building workers in their national strike in 1972, the print workers at Wapping, and the dockers also blocked cargo coming from apartheid South Africa.

In the early 90s, the dock company informed the union that they were introducing a 3-way working system. The shifts would be 7am to 3pm, 3pm to 11pm and 11pm to 7am at the ships. At the groupage [organising goods into similar types for transit], though, this would be 8am to 5pm. This worked for a short while, but then it became obvious that this system would not work, because dockers were turning up for their shifts and if no ships had come in, they were allocated maintenance work such as cleaning the quayside and repainting lines on the ground where the containers were packed.

Seaforth Dock opened with scab labour

The only way to make sure that they had enough man cover for the ships was by turning the 8-hour shifts into two 12-hour shifts. Most of the men were unhappy about this because you couldn’t book any time off, such as for family functions.

This resulted in 220 being suspended from work on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day. The men were often calling to take strike action against the working conditions. Then, in September 1995, it resulted in all of the dockers being sacked (see below).

Seaforth Dock was only closed for four days, then it was re-opened with scab labour from Southampton: the speed with which this was set up suggested to me that this dispute had been initiated by the dock company. The dock company had been told about the picket going on at the gate and I was told by the dock company director that they would not be closing Seaforth and if there was a strike, not all of the men would be returning to work. The dock company offered 200 men new contracts, but the offer was refused. This was a blatant attempt to split the men.

The background to the 1995 strike

With the election of the Tory government under Margaret Thatcher, she was intent on abolishing the National Dock Labour Scheme (which she eventually did, in 1989).

Initially, this resulted in the National Dock Strike in 1981 for six weeks. At a mass meeting in the Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool, the then General Secretary, Ron Todd, came down from London and addressed the meeting. There was uproar at the meeting when he told us that he had got the best deal he could and there was another severance offer of £25,000. At that time, most smaller stevedoring companies had ceased to exist and so it was only the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company that serviced the port.

As a result of the agreement, sold to us by Ron Todd, the remaining dockers would be allocated to six areas that the dock company looked after, eg, the cargo handling, the grain, the ferries, the timber terminal, the container terminal and the Pandora [shipping container]. The outcome of that offer was that a lot more younger dockers accepted the severance.

The shop stewards’ movement looked after the dockers in the work place and over the years most advances in pay and conditions were won by unofficial action and not by the [national] union. The labour force was still dwindling and there was a lot of unrest.

I had now moved to work at the Belfast ferries, based at the Langton Dock, as the clerk in charge, but I was still employed by the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company. The Belfast ferries pulled out of Liverpool and so I moved then to the Royal Seaforth container terminal as a clerk. I trained up to be a straddle carrier. This is a machine that lifted the containers on and off wagons. They also took the containers to and from the ships and to the standing areas.

Shortage of dock workers and Torside

I had been a shop steward before and was elected again to be a shop steward at Seaforth in 1992.

What happened was that too many men had been allowed to leave the industry and so the dock company told the union that they needed to recruit, because they had a shortage of labour in the cargo handling area. There had been no intake of any dock workers since the abolition of the Scheme.

A new company called Torside was set up by Bernard Bradley. With the union’s help, he was allowed to recruit eighty dock workers to help in the cargo handling areas.

Most of those employed were young men who worked alongside registered dockworkers on the same conditions. This seemed to work well for a while, until 1995, when five of the new recruits were sacked by Bernard Bradley, the reason being that they were asked to work overtime and the men asked whether they were getting the agreed rates of overtime. They were told ‘no’, so the outcome was that they refused to work and went to the canteen. Bernard Bradley stormed into the canteen and sacked five of the young Torside dockers who refused to do overtime, which caused a dispute at the vessel, which led to strike action by the rest of the Torside dockers.

The union became involved and the District Secretary at the time was told by the Torside dockers that they were going to picket the Royal Seaforth container terminal, to get support from the rest of the dockers. He told them Seaforth had nothing to do with them, and to stay away. The Torside dockers ignored him and picketed the gate at Seaforth. The Seaforth dockers refused to cross the picket line, resulting in a mass meeting at [TGWU headquarters] Transport House, where all the dockers agreed that the picket line would not be crossed.

Accept new terms – or be sacked

This led to the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company sacking the entire dock labour force. The response of the dock company was to issue the entire dock labour force with letters of dismissal, which stated that if they did not return to work – and this included people who were off sick or on holiday – they were to be dismissed.

I was on nights at the time and was given the letter when I got up from bed by my wife. I saw this coming because I believed that Torside was set up by the dock company, the reason being that the ships that were serviced by Torside dockers all had supervisors who were employed by the dock company.

A mass meeting was arranged at Transport House for all the sacked dockers. The union told us that they could not make this dispute official but the dockers still set up picket lines on the Gladstone and Seaforth gates. The union told us we had to return to work and so we tried to return to work, but the gates were locked against us. And so we then returned to the picket lines.

This resulted in the Liverpool dockers being in dispute for 28 months, with no strike pay from our union. We had to rely on donations from other trade unionists and support from the general public, which we received not only locally but nationally, and then internationally. Delegates were sent, including myself, to the USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, France, Denmark, Sweden and other European countries.

Help came nationally and internationally

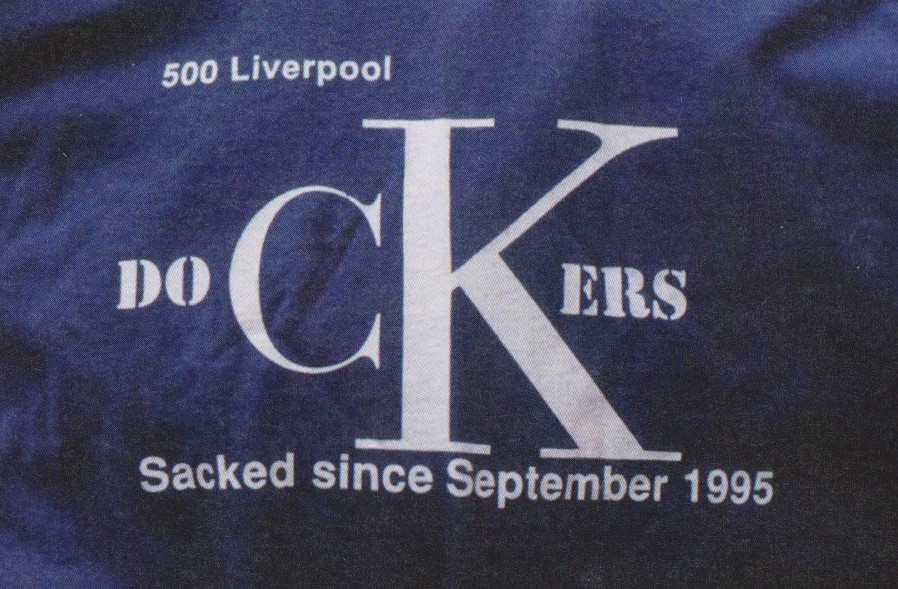

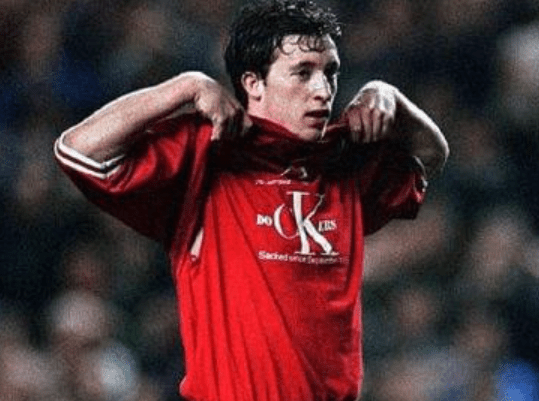

During that time we had regular rallies attended by thousands of supporters from all over the country and internationally, including people from the Turkish Kurd community. We also set up T-shirts with ‘Help the sacked dockers’ on the front.

Sadly, after 28 months in dispute, another meeting was called at Transport House, and the dispute committee, made up on former stewards and others, informed us that the dispute was over, and that was the end. Most of the men that had been sacked had given between twenty- and forty-years’ service and were told they would receive a £25,000 payout. Is that justice?

I called this a dispute because we were sacked for not crossing a picket line. We were not on strike and we were in dispute with the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company.

The situation today

I have been a member of the TGWU/Unite since 1964 and I am still a member in spite of what happened. People join unions for the unions to look after their pay and conditions as well as health and safety in the workplace. Sadly, since the introduction of the Anti-Trade Union Laws, you now have to give notice of any strike action, which I think suited some union leaders who would say that they would like to support, but their hands are tied.

Some general secretaries of some unions are more interested in promoting themselves instead of looking after their members. At the time of our dispute, Bill Morris was general secretary. He became Sir Bill Morris and he now sits in the House of Lords as Bill Morris, Baron Morris of Handsworth. Another general secretary, Tony Woodley, Baron Woodley, also sits in the House of Lords.

The greatest general secretary that the TGWU had in my opinion was the true socialist, Jack Jones, a man who fought in the Spanish Civil War and was wounded. He refused a knighthood. He said he did not want to go to the House of Lords and instead when he stepped down from the TGWU, he became the leader of the National Pensioners’ Convention.

Where does power lie?

The minimum wage was brought in by Blair’s New Labour government. It was set at £4 an hour and was opposed by the Tories and the CBI. Although welcomed by myself and the unions, the rate should have been higher. When the Tory government was elected, although they opposed the minimum wage, the then Chancellor hi-jacked it and renamed it ‘The National Living Wage’, which set up the working practices which we have today, ie part-time work, zero-hours contracts and the explosion of agency labour which at the moment is rife in this country and has eroded workers’ rights.

Workers have no rights to take their grievances to an industrial tribunal if they have not been employed permanently for two years, unless they are a member of a trade union. How many workers who are not in unions can afford to pay for tribunals?

CBI seem to be winning hands down

It is my belief that the employers thought the unions had all the power, when in fact the power is only in the hands of the bosses, as I have stated previously. The CBI (the bosses’ union) seem to be winning hands down, taking into account the paying conditions in retail.

All the major supermarkets have attacked the conditions in the sector that is basically a seven-day week. Recently, some workers in the stores have had a partial victory, and won a claim to be paid the same rate of pay as the workers in the warehouse. But sadly, the employers are appealing the court decisions, and it looks like it could take up to three yeas for them to get the money they are owed. And it is my belief this is because most of the workers in this sector are not in a union.

We have seen the way successive Tory governments and the Tory/Lib coalition have treated workers in the past. With ten years of austerity and now during the worst pandemic in over a hundred years, we have witnessed chumocracy being dished out to Tory supporters, some with no experience of making PPE. Some of these companies have made millions, and now we see the results of how NHS and indeed all essential workers are being treated, most having to do with a pay freeze, with the NHS having been offered a derisory one per cent.

This is what we expect from the Tories. One of Johnson’s Bullingdon Club pals, Ewen Ferguson, was appointed to the Independent Sleaze watchdog and had been at university with Johnson and David Cameron in 1987. He will now join the Committee on the Standards in Public Life. Sir Alistair Graham, a former chairman, branded the appointment ‘pathetic’. Angela Rayner says it is more cronyism and he doesn’t even care to hide it. So this is Tory Britain in the 21st century. I believe that you get what you vote for, so be very careful when you use your vote next time.

Author’s note for the Second Edition:

When they are giving the weather report, they start by saying ‘at the start of the working week’ or the ‘end of the working week’. This is not factual, because the working week is seven days, not five like it used to be.

And at all the top supermarkets, the staff are not on 40 hours a week; they can be on 16 to 40 hours, so overtime is not paid. If they are asked to work extra hours they are called ‘extended’ hours, which are not paid at overtime rate. The supermarkets have tried in the past to get Sunday hours extended, so they can have workers doing longer hours at the same rates.

Luckily, the government hasn’t agreed to this…yet! The scourge of the modern-day workplace is the phenomenon of ‘fire and rehire’, which is the latest attack on workers’ rights. It has been used on British Gas engineers, British Airways staff, as well as leisure centre workers and hospital workers in the Midlands. We can expect a lot more of this practice, while the unions and the TUC seem to be doing very little to combat this.

The effect on the High Street has changed that much; where we had local shops and banks and building societies, we now have betting shops, charity shops and empty shops.

Mike Cullen was a Liverpool docker from 1965 to 1995. He lives in Birkenhead with his wife, Nita. This booklet was first published in April 2021 and updated later this year. We are grateful for his permission to republish the booklet on our website, but anyone who wants a hard copy should contact Mike via michael.cullen2@sky.com