By Andy Ford, Warrington South Labour and Unite member

The Battle of Moscow, 80 years ago this month, was the biggest battle of the Eastern Front and the whole of the Second World War. Seven million men and women were involved, of whom two and a half million were killed, captured or wounded. The Russian records show 958,000 killed, missing or captured and another 930,000 wounded. On the German side, 615,000 were killed or wounded. By comparison, the battle for Stalingrad involved half the number of troops.

At stake was the Soviet capital, the centre of government, the road and railway networks, and significant amounts of industry. The German High Command wrote at the time, “The object of operations is to deprive the enemy…of his government, armament and traffic centre around Moscow, and thus prevent the rebuilding of his defensive forces and the orderly working of government”.

The Nazis’ calculation was that a defeat here would knock Russia out of the war and allow them to turn back to Britain and North Africa. And, who knows, they could have been right. In September, Hitler told his adjutant, Otto Gunsche, “We will break them soon…Moscow will be attacked and fall, and then we will have won the war”.

Operation Typhoon: the German attack on Moscow

The battle was preceded by a German offensive aimed at the capital, Operation Typhoon. Even though the German tactic of panzer breakthroughs, followed by mass encirclement, was still working, it was becoming more costly. For instance, in the Battle of Smolensk in July 1941, which cleared the way to Moscow, Germany captured around 350,000 men, but they still lost 35,000 killed or missing themselves, as well as 100,000 wounded and losing 200 tanks. It had been a tremendous defeat for the Red Army, but not without cost for the Germans.

As the Germans advanced, the resistance grew more determined, and their supply lines were stretched out. Warning signs were beginning to appear. Just after Smolensk, the German panzers encountered their first Soviet T-34s and were badly mauled. German tank commander Guderian later wrote “This was the first occasion on which the vast superiority of the Russian T-34 to our tanks became plain”.

He also saw that fuel was occasionally running out and that no winter clothing was being issued. He also noted in his diary “The bitterness of the fighting was gradually telling on both our officers and men. It was startling to see how deeply our best officers were affected”.

Hitler ordered Operation Typhoon in early September. The plan was to encircle the Soviet armies in the area forward of Moscow and so deprive the capital of its defenders. Troops were transferred from the siege of Leningrad to build up German forces debilitated by the war so far. They had lost 1,488 armoured vehicles and received just 96 replacements, and 20% of German tanks were being refitted in the rear. Nevertheless, the attack, by a total force of 1.9m men, was set for the night of October 1.

Trams were still running in Orel

On October 3, the German tanks reached Orel, 200 miles south-west of Moscow. They had advanced so quickly that the trams were still running on time. While the Red Army was trying to contain this attack in the south, a second German force broke through the Russian lines in the north, and linked up with the first at Vyazma, encircling nearly a million men. The generals pressed Stalin to allow a withdrawal, but he hesitated, leading to the capture of half a million Red Army soldiers in and around Vyazma and a further 85,000 in Bryansk. It was a disaster. The Russians had lost nearly half their forces and the road to Moscow was open.

The Germans and much of the world’s press predicted the capture of Moscow within a month. In Moscow, the NKVD began putting explosives on the bridges and getting ready to destroy the factories, but this only served to sow panic in the population. The roads east were jammed, workers began not showing up to their workplaces and on the night of October 17 looting broke out across the city. All seemed to be going to plan for Hitler.

On October 18th Stalin went to the Kursky station where his special train was waiting, but suddenly turned round and returned to the Kremlin. He then declared martial law and vowed not to leave the city. It was clear that Moscow would not be surrendered.

At the same time, the first snows came in early October and this was followed by the Russian raspusitsa, literally the ‘time without roads’, which often left whole convoys of German vehicles stranded in the mud. And the encircled Russian troops at Vyazma carried on fighting, tying up 28 German divisions. The Germans could hardly believe their tenacity in a hopeless situation. But by that time the Red Army soldiers knew that to be captured meant likely death by starvation, and the German order to shoot all Commissars (and female soldiers) on capture only stiffened their resolve. All this bought time for the Russians.

On October 6 Stalin had placed Zhukov, one of the few capable generals to survive the purges of the late 1930s, in charge of the defence. Zhukov’s report was grim: “There is no longer a continuous front in the west and the gaps cannot be closed because the command has run out of reserves”. He calculated that he had only 90,000 trained troops to defend the capital.

Civilians mobilised in thousands to dig defences

Zhukov decided to construct a defence line, the Mozhaisk Line, about 80 miles west of Moscow. The citizens of Moscow, just like those of Leningrad in September, were sent out in their thousands to create the necessary defences of ditches, tank traps, barbed wire and felled trees, while they were attacked by Luftwaffe fighters.

A textile worker, Olga Sapozhnikova, was quoted as saying “Those were dreadful days. On the very first day we were machine gunned. Eleven of the girls were killed and four wounded.” But air raids cost the Germans dearly, as 40% of the Soviet air defences were situated in Moscow, manned mainly by women, so the Luftwaffe lost hundreds of aircraft.

On the Mozhaisk Line, many positions were held by Home Guard or militia units, but they were facing hungry, exhausted and freezing German troops. A German officer, Kurt Gruman, complained in his diary of how the cold, at minus 9 degrees “tortures us” at night. On November 24, he recorded that “Each day the combat strength of our troops weakened”, describing his men as “tired, louse-infected and reduced in numbers” and complained that they were “unable to break the enemy resistance.”

Japan and the USSR

The Soviet Union had one large force left – its Siberian armies in the Far East. But they needed to know whether or not Japan would attack. One faction of the Japanese military remembered their defeat by the Red Army in Mongolia in 1939, but another faction saw an opportunity to avenge it.

The Soviets had a ‘source’ in the highest circles of the German community in Tokyo, in the character of Richard Sorge, outwardly a German newspaper correspondent, but actually a committed agent for the Soviet Union. In June he had annoyed Stalin by warning him repeatedly of the German invasion; now he was tasked with determining Japanese intentions.

But the Japanese constantly flipped between their two options – to attack the USSR at its moment of weakness, or to turn south to the defenceless imperial possessions of France, Holland and Britain. In early July, they reinforced Manchuria; but on the July 28 they took over French bases in Vietnam. Finally, in September, Sorge learned that the Japanese army were being issued with shorts – so their attack would be to the south.

He transmitted this information to Moscow, and this time he was believed. Starting from October, and throughout November, a quarter of a million well-armed, well-clothed, and experienced Siberian troops were taken by special trains to Moscow.

Stalin’s speech of November 6

Probably as part of this game of bluff with Japan, Stalin, incredibly, decided to hold the usual November parade in Red Square for the anniversary of the Revolution – with the Germans less than 200 miles away! The previous night, Stalin assembled the Soviet leaders and the world press in the Mayakovsky metro station for a speech, which was described by British correspondent Alexander Werth as “A strange mixture of black gloom and complete self confidence”.

With huge understatement, Stalin declared that “the danger, far from diminishing, has increased.” He followed this with totally unbelievable figures, outright lies, for Russian and German losses: one million Russian dead, captured and missing, compared to over four million for Germany. He made excuses for the loss of Russian tanks and aircraft, by blaming the factories for production hold ups, not mentioning the material lost without a fight because of his errors at the start of the German attack. And he emptied the war of all class content, harking back to Tsarist generals and the victory against Napoleon, and invoking the spirit of Russian patriotism and nationalism.

Stalin’s non-class approach guaranteed German resistance to the end

Finally, he echoed Hitler’s words of a ‘war of extermination’ saying: “The Germans want a war of extermination against the peoples of the USSR. Well if the Germans want a war of extermination, they shall have it.” With those words, Stalin virtually guaranteed that German Army would fight to the end, just like the Soviet troops in Vyazma.

It is interesting to compare Stalin’s crude mish-mash of nationalism and excuses with Trotsky’s words when he commanded the Red Army. On lying and propaganda, said that “Lies will be punished as treason. Military work admits errors, but not lies, deception and self-deception.” As opposed to a war of extermination, Trotsky’s view was, “woe to the unworthy soldier who raises his knife over a defenceless prisoner or deserter”.

And on war as class war, even as British planes bombed Red army positions in 1919, he wrote, “To-day, when we are engaged in a bitter fight with Yudenich, the hireling of England, I demand that you never forget that there are two Englands. Besides the England of profits, of violence, bribery and bloodthirstiness, there is the England of labour, of spiritual power, of high ideals of international solidarity. It is the base and dishonest England of the stock-exchange manipulators that is fighting us. The England of labour and the people is with us.”

Trotsky’s approach meant that the invading armies in the Russian Civil War dissolved from the inside, whereas Stalin’s approach ended up turning the war into a brutal slog from the gates of Moscow to the Berlin bunker, costing millions of Red Army soldiers their lives.

The Nazi gamble: the final lunge at Moscow

In 1941, the German strategy had been to encircle Moscow from the north and south and so avoid the defences of the Mozhaisk Line. Their aim was to surround the city, wipe out the defenders and starve the inhabitants. One set of fanciful German orders even set objectives 80 miles east of Moscow.

Once the ground froze solid, the elite SS Das Reich panzer division was despatched east to engage the Mozhaisk Line. Hitler had promised them the honour of being first into Moscow. But far from an easy victory, they were caught by prepared Soviet defences and sustained heavy losses, losing most of their officers.

To the north, the Germans crossed the defences on the Volga canal on November 15 and advanced to the town of Klin, just 70 miles from the Kremlin. But on November 29 they had to abandon their bridgehead over the canal in the face of the resistance, and go over to the defensive.

One column of motorcycle troops typified the Nazis’ problem – they broke through a gap in the Russian lines and advanced to the Moscow suburb of Khimki, 18 miles from the Kremlin. But they had no back up and were at the end of a very long and dysfunctional supply line for ammunition and fuel. They were mopped up by the local militia and the survivors fled back to their positions, claiming to have seen the Kremlin through their field glasses.

Germans could do no more and offensive was halted

In the south, Guderian was ordered to capture the industrial city of Tula, 120 miles from Moscow, and a centre of arms production, on the same day as the attack in the north commenced. But the Russians held out and even threatened to surround the Germans from their west. When fresh Soviet troops appeared to his east, Guderian told his high command that he could not reach Tula, was in danger of encirclement and had only 150 tanks operational out of 1,000.

Despite Hitler’s exhortations, the local commanders realised that their men could do no more and stopped all offensive action. They were now camped out in the open in the middle of a Russian winter, with no prepared positions, no winter quarters and no warm clothing. They could not even prepare better positions to their rear as there were simply not the materials or men to do it.

The plan had been to occupy Moscow with a garrison force over the winter. Instead, the whole army was camped out in temperatures of minus 20 degrees and locked in combat. Reassuringly, German intelligence estimated that the Soviets would not be capable of mounting any attacks that winter. How wrong they were.

Red Army reply: the Battle of Moscow

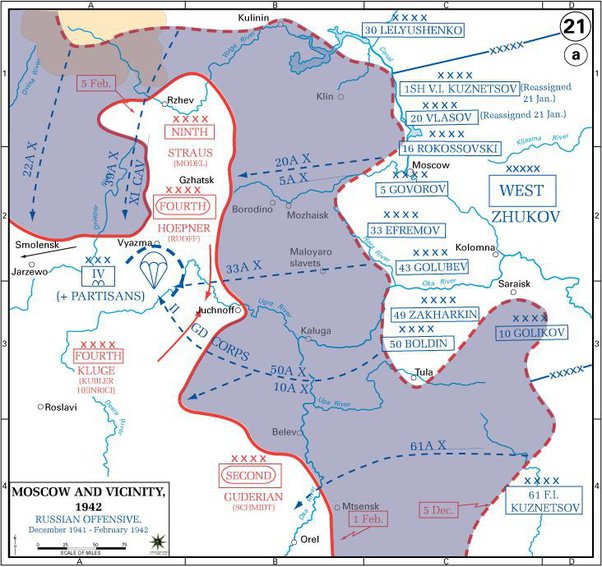

At dawn on December 5, the Russians counter-attacked with just over a million men. It was minus 15 degrees Centigrade, and the snow was three feet thick. Their aim was to encircle the two German pincers, north and south, and they very nearly succeeded. However, the German commanders just managed to pull their forces back before Hitler could issue one of his “No Retreat!” orders.

In fact, just like later in the war, Hitler could not see the reality, still ordering the creation of a defensive line on December 8, just when the Wehrmacht was in headlong retreat. German pilots reported seeing hundreds of discarded German tanks burning on the roads, and Kurt Gruman’s diary recorded a collapse in morale. “Have we not been abandoned?” he wrote.

As thousands of wounded and frostbitten soldiers returned hospitals in Germany, Goebbels complained that “The anxiety of the German people about the Eastern Front is increasing” and that “Words cannot describe what the soldiers are writing home from the front”. His arrogant bubble had well and truly burst.

Generals wanted to retreat in good order

The Germans were now caught in a bind – to stay and fight meant encirclement and capture, but to retreat meant losing all the heavy weapons. On the horns of this dilemma the command went into confusion and paralysis. Hitler and his sycophants said retreat made no sense, if it left the armies in the open with no heavy weapons, while the generals in the field wanted to retreat in as good order as could be maintained, even if it meant losing equipment.

Then on December 18, well-armed Siberian troops attacked in the centre. German General Halder’s diary read simply “Attacks everywhere”, and General Jodl openly compared their situation to Napoleon’s in 1812. On December 19, Hitler sacked his Commander-in-Chief and assumed the role himself, with fateful consequences for the rest of the war. Other generals were dismissed or stepped down; the German army was in crisis.

It was at that point that Stalin’s errors saved the Germans. His generals, Zhukov and Rokossovsly, wanted to concentrate their forces to surround and destroy the German Army Group Centre. But instead, Stalin ordered a general offensive from Leningrad to the Black Sea, with the predictable results of huge Soviet losses, where they attacked prepared German defences, and piecemeal gains where they did not. Around a million Russian soldiers died in the failed campaign to retake Rzhev in early 1942. By March, the Germans had been driven back about 150 miles from Moscow, but the front resembled an unfinished jigsaw.

German failure and its effect or Lessons of Moscow

The German defeat at Moscow revealed Operation Barbarossa for what it had always been – a gamble. It was all based on Hitler’s belief that if he “kicked in the door” the whole structure would collapse. Instead, as the Wehrmacht drove further into Russia, their difficulties increased while Soviet resistance increased. The tipping point was at Moscow.

Secondly, it showed the importance of the class nature of the Soviet regime. Despite its crimes against the original leadership of the Bolshevik Party, the Trotskyists, Soviet workers and peasants, and finally the Red Army officer corps, the Stalinist state still rested on state-owned property and a planned economy. It could organise the massive production of war materials and out-produce capitalist Nazi Germany by far, but could also tap into the mass mobilisation of the population of Moscow.

Unlike as happened in France in 1940, where the ruling class decided that they could stomach being junior partners to the Nazis, rather than arm the working class for a life and death struggle, the Soviet leadership had no such option. They needed the state-owned planned economy, even if only so they could carry on robbing it.

Thirdly, the ‘backward’ Soviet Union turned out to be pretty good at the design and mass manufacture of all the instruments of war, the best known example being the T-34 tank, but also the Katyusha rocket system, theYak-9 fighter and the PPS sub-machine gun.

And lastly, the command and leadership style of Stalin is there to see with all its deficiencies. One example is given by Zhukov in his memoirs. When Stalin heard that the Red Army had lost a town called Dedovsk, just 20 miles from the Kremlin, he ordered Zhukov to go there and personally organise the counter attack. Even when Zhukov reported that they had not actually lost Dedovsk, but a similar sounding village called Dedovo, Stalin flew into a rage and told him to retake Dedovo anyway. Red Army soldiers were diverted to attack a few strategically unimportant houses, and at great cost.

Stalin’s refusal to allow a timely withdrawal from Vyazma condemned hundreds of thousands to death or captivity. Their bones are still being dug up to this day. And the way he ordered attack all along the front in early 1942, lost the chance to destroy German Army Group Centre and left Hitler free to try once more to knock Russia out of the war in 1942, this time by attacking towards Stalingrad and the Caucasian oil fields.