By Harry Hutchinson, member of Labour Party Northern Ireland

The final report of the Commission on Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition in Northern Ireland was published last November but it has offered nothing we didn’t already have or told us anything we didn’t already know.

The political career of Mike Nesbitt, once leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), shows the extent to which sectarianism is built into the political establishment. In 2017, he made an extraordinary announcement, claiming he would vote for the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) instead of rival unionist candidates. He also claimed he wanted to attend Sinn Fein’s Ard Fheis (conference). Nesbitt’s aim, he said, was to create a more inclusive society in Northern Ireland and challenge the more sectarian parties that were in coalition at Stormont.

His claim caused outrage in unionism and also within his own UUP. In addition, there was no attempt from the SDLP leader to embrace Nesbitt’s offer. Within months, and after some poor election results, Nesbitt was forced to resign as UUP leader. But resigning as leader was not enough. The problem for the establishment was that Nesbitt could and probably would remain popular among some people in Northern Ireland, so it became necessary to destroy his reputation. Three months after his resignation, he was photographed lying, perhaps intoxicated, in a Belfast Hotel.

The photo was broadcast across the North, particularly by the BBC, the main propaganda output for capitalism in the UK. Later, the media again targeted Nesbitt after he apparently breached Covid restrictions. Both of these incidents were enough to destroy Nesbitt’s public image.

Report on the commission on Flags and Identity Culture and Tradition

Where did the Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition Commission come from? In 2016 a report was commissioned by the Northern Ireland Assembly to look into areas of conflict and to make recommendations to resolve them. From the outset, the Commission was doomed to failure. Of its 15-member committee, almost half comprised of members of the various sectarian parties; two DUP, two Sinn Fein, one UUP, one SDLP and only one Alliance (the only nominally ‘non-sectarian’ party). The rest of the committee was made up by so-called independents.

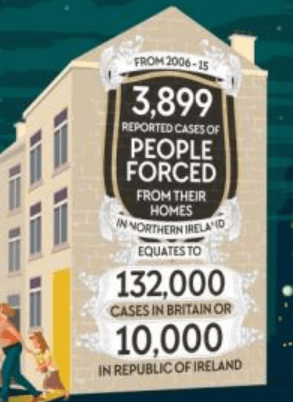

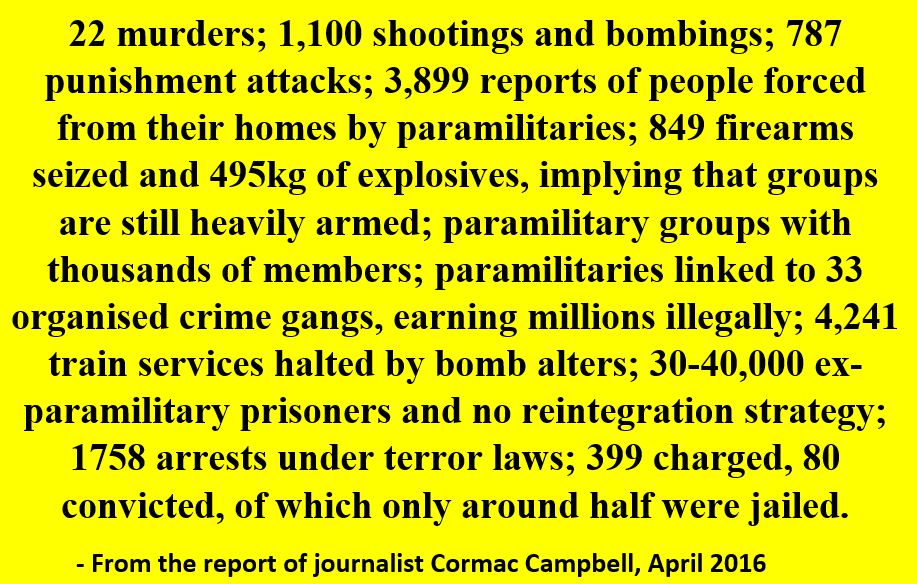

At the time the commission was set up, it was challenged to recommend some meaningful changes that would address the problem of the sectarian paramilitaries that still existed. In a powerful article and video, the full extent of paramilitary activity – at that time eighteen years after the Good Friday Agreement – was spelled out (see graphic left). Five years on and finally in November the Commission reported its findings. But there is no sense in which it has met the challenged made in 2016.

The commission’s report identifies a number of ‘areas of conflict’ that needed addressing, including flags, bonfires, murals, and the use of public spaces. The commission even discussed replacing the national flag and replacing it with a civic one. But after years, and costing over three quarters of a million pounds, it offers not one single recommendation to resolve any of the issues of sectarian friction or conflict that were identified. This includes, just to take one example, the vital need of integrating education, where at present only 7% of children in NI attend an integrated school.

Forced divisions in the North

Division in Northern Ireland has been maintained historically to keep sectarian and pro-capitalist parties in power. These parties legislate in the interest of the big corporations and the wealthy and do nothing to ameliorate the daily problems facing ordinary workers. The Unionist and Nationalist parties, along with their paramilitary associates, do their best to entrench divisions by all means necessary, including ethnic cleansing and attacks on migrants. The vast majority of people in the North still live in single-identity communities. Any attempts to unite people will be resisted by the sectarian parties.

As long as there is no outright conflict between Catholic and Protestant communities, there is some natural tendency for people in Northern Ireland to move, albeit slowly, in the direction of integration. Increasingly, younger people particularly identify as being ‘non-religious’ and fewer vote in elections for the two dominant sectarian capitalist parties. If there was an all-Ireland working class party that was based on the trade unions and community campaign groups, it could reinforce that tendency and provide a solid basis for uniting the people in Ireland North and South.

On the other hand, as the FICT commission report indicates – still, nearly twenty four years after the Good Friday Agreement – the potential for sectarian conflict that still exists. The paramilitary organisations still exist on both sides of the sectarian divide; the loyalist groups alone have more than ten thousand members, many of them involved in crime, harassment and intimidation in local communities.

Despite the overwhelming desire not to go back to the killings and brutality of the ‘Troubles’, Northern Ireland is still a powder-keg. The report of the commission on Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition’ told us nothing we didn’t already know. But the complete vacuum in its recommendations is a warning, because as in nature, politics abhors a vacuum and if the labour movement doesn’t intervene in the future, there is still the possibility that sectarian paramilitaries will step in once again.

As socialists, we must explain that attempts to bring capitalist, sectarian parties together will never advance society. Uniting working people though the struggles of the trade unions and communities to address areas of concern to workers is the only means of cutting across divisions and that is the basis of building an integrated movement.