By John Pickard

One of the most controversial issues in the trade unions and the Labour Party is the question of whether or not the labour movement should support nuclear power. Nuclear power claims for itself the advantage of being ‘non-carbon’ and therefore a reliable ‘green’ source of energy, but there is more to it than that.

The next Left Horizons Zoom discussion, on Tuesday January 25th, will focus on this issue and examine some of the issues that need to be addressed.

The starting point has to be the fact that there are many tens of thousands of jobs – and many of them highly-paid, skilled jobs – in the nuclear energy sector. This is reflected in resolutions to TUC and Labour conferences from key trade unions in the field.

It is not by accident that resolutions passed by both conferences, always moved by trade unions in that industry, have called for a “just transition” to green energy. The resolution at TUC conference last year noted that “the climate emergency is the gravest threat currently facing humanity” but it called for “a balanced energy mix that includes renewables, nuclear, and the flexibility currently provided by gas.”

This resolution, which was very wide-ranging and dealt with all aspects of energy, ‘greening’ industry and transport, was moved by the GMB and called explicitly for “the construction of new nuclear plants, benefiting communities from Sizewell to West Cumbria, and the development of Small Modular Reactors”

Part of a ‘mix’ of energy sources

In a similar vein, the Labour Party conference a few weeks afterwards passed a composite, again moved by the GMB, supporting nuclear power as a viable energy source for the future. “The UK’s pathway to 1.5°C”, it said, “needs a balanced and secure energy mix that includes renewables, nuclear, and the flexibility currently provided by gas and in future by fuels including hydrogen…” Like the resolution at TUC (and probably modelled on it), it too called for “new nuclear plants, including Sizewell C and Small Modular Reactors”. Last but not least, the Labour Party election manifesto in 2019 also called for the construction of new nuclear power stations.

Whether nuclear power should form part of a mix of energy sources for the future, is a controversial issue in itself, but what should be non-negotiable for the Labour Party is the idea of what the unions call a “just transition”. The first point for any socialist energy policy has to be the maintenance of the jobs and livelihoods of the tens of thousands of workers and their families who currently rely on nuclear power.

Until such time as workers can be retrained, reassigned or otherwise redeployed into non-nuclear energy production or other industries – and that has to be the aim in a socialist planned economy – then the livelihoods of workers in those industries have to be protected. That has to be a key bullet point in the policy list for any incoming Labour government.

The most important reason why socialists object to nuclear power is the largely unresolved problem of nuclear waste. All radioactive substances are all to one degree or another injurious to health and exposure to radiation can cause cancers, birth defects or early death, depending on the severity of the exposure.

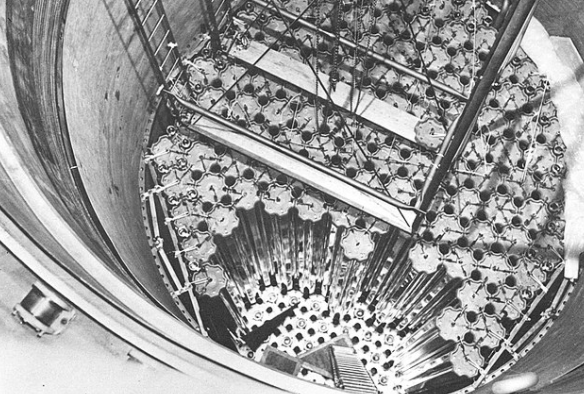

Most nuclear power stations use one of the isotopes of Uranium as the main source of power, the metal being concentrated into pellets which are packed into fuel rods. Uranium is a highly radioactive metal which occurs naturally in many parts of the world, although in small quantities and so widely ‘diluted’ among other minerals and rocks that it is effectively harmless. Uranium can only be made useful by ‘enriching’ the natural ores to a much higher concentration of the metal, to ten or more times natural levels.

Thousands of tonnes of Uranium every year

A single 1 GW pressurised water reaction uses around 27 tonnes of Uranium a year, made into millions of fuel pellets in thousands of fuel rods. So the exploration, extraction, enrichment and transport of Uranium on a global scale is a massive industrial and commercial process in its own right.

Once Uranium fuel rods are produced and then inserted into nuclear reactors to generate heat – and thereby electricity – the difficulties begin. After a relatively limited period of time fuel rods are no longer effective and need to be replaced. The ‘depleted’ Uranium rods can be reprocessed to be used again, but there is a limit to how efficient this can be and so inevitably, some Uranium ends up as nuclear ‘waste’ along with other highly radioactive elements like Plutonium.

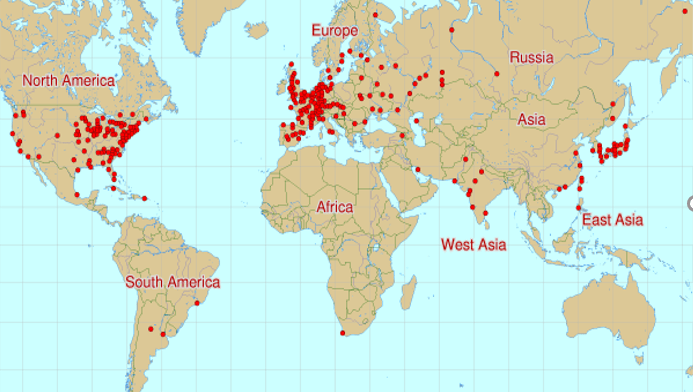

The argument about waste is probably the single most important issue that creates objections to nuclear power. Every nuclear power plant in the world – and there are hundreds now – produces high, medium and (so-called) low level nuclear waste and there is an ongoing and permanent problem of what can be done with it.

A lot of so-called low-level waste is simply stored above ground, in huge lakes dotted around the nuclear sites. There is an expectation that there will be no loss of integrity or leaks as the low-level waste gradually becomes ‘safe’ over the decades.

Other, higher level waste is storied deep underground, where it is supposed to be out of harm’s way. There is always a danger, however, that radioactive elements end up being released into the environment or find their way into the atmosphere or the water supplies, as a result of geological movements and disturbances.

Half-lives of millions of years

Many nuclear waste-products will remain dangerous for thousands of years. The two main isotopes of Uranium, for example, have a half life of 700 million and 4.5 billion years, so the presence of either of these in the waste – and it is not uncommon – renders it extremely dangerous. Plutonium also occurs in small amounts in some waste and has a half-life of ‘only’ 24,000 years. Simply dumping waste in a local pond or down an old mine shaft, therefore, is kicking a very dangerous can down the road and effectively leaving the problem for future generations to deal with.

There have been major accidents in nuclear power plants in the past, such as at Three Mile Island (1979), Chernobyl (1986) and Fukoshima (2011). Each of these has resulted in a widespread distribution of radioactive materials and has impacted on the health of those affected, causing an increase in birth defects and cancers. The Fukoshima accident arose, let us recall, from a tsunami in the Pacific, which itself was caused by an earthquake, an event that could not have been predicted.

Adding together all of the difficulties of nuclear power, moreover, there is a question mark about its true efficiency as a means of generating electricity. We have to take into account not only the nuclear power plant itself, but the ‘before’ and the ‘after’.

There is the mining of thousands of tonnes of ore every year, the enrichment and transportation of the Uranium, as well as the further reprocessing and, not least, the enormously complicated process of storage of nuclear waste. All of these processes are in themselves extremely energy-intensive, using huge amounts of electricity – which means, at present, carbon-based fuels. ‘Clean’ energy, it most certainly is not, when all the add-ons are put into the calculations.

Nuclear electricity more expensive than wind or solar

It is not surprising that economic modelling for new nuclear energy plants, suggest that for each unit of electricity they will produce, they are far more expensive than solar or wind power. It is one thing, therefore, for the GMB and other trade unions to fight to preserve the living standards of their members in the nuclear industry – and socialists would support them in that – but it seems completely illogical to advocate the building of new plants, costing the tax-payer billions of pounds, only to produces energy that is more expensive than solar and wind-power.

There is a more than a suspicion that the preservation of a nuclear industry has less to do with electricity production as such, than it has to do with maintaining the technological foundation for an arsenal of nuclear weaponry. When it comes to states elsewhere in the world, like Iran and North Korea, it is precisely the issue of nuclear weapons that leads Western states to oppose the building of nuclear power stations. From the point of view of energy production, there can be no justification for a dangerous and expensive industry to be favoured on ‘military’ grounds.

The one single advantage that might be given to nuclear power is that unlike wind and solar, it can provide continuous production that is completely independent of climate and weather. But even that advantage would not matter so much if there were efficient networks, grids and storage capacity to compensate for weather variations from one region or state to another. Then again, geothermal, hydroelectric and tidal energy are renewable and carbon-free and are completely independent of the weather and these are sources that could be developed.

These and many more related issues should be the subject of discussion and debate inside the labour movement. We may have a particular view on the viability and advisability of using nuclear power as part of the ‘mix’ within a socialist energy plan. But we need to recognise that there are many good activists and socialists who think otherwise, for what they see are good reasons and they need to be part of a dialogue.

Come to the Left Horizons discussion next week; listen in and put your point of view. The link for the meeting can be found on Facebook, or directly to Zoom here.