By John Pickard

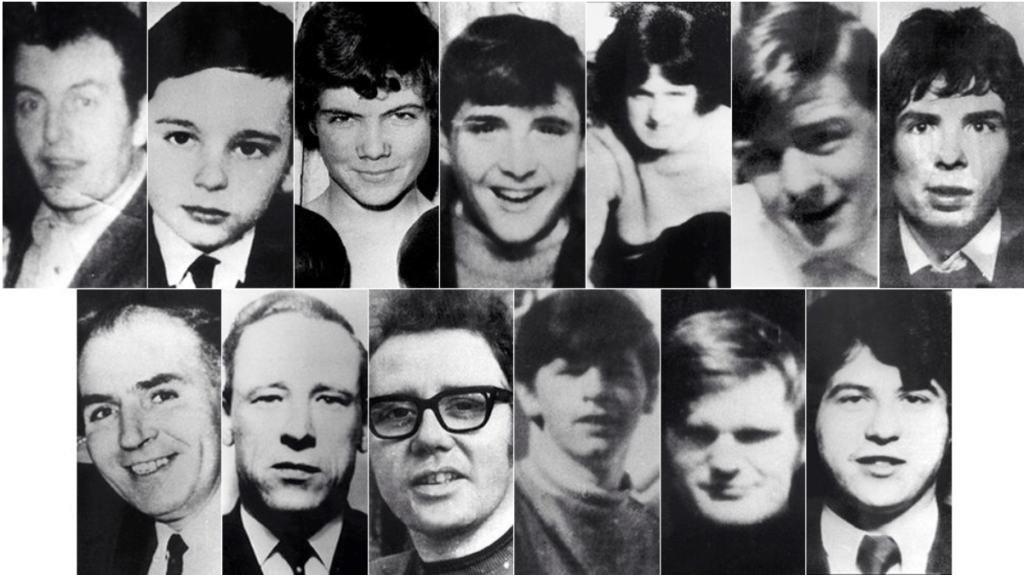

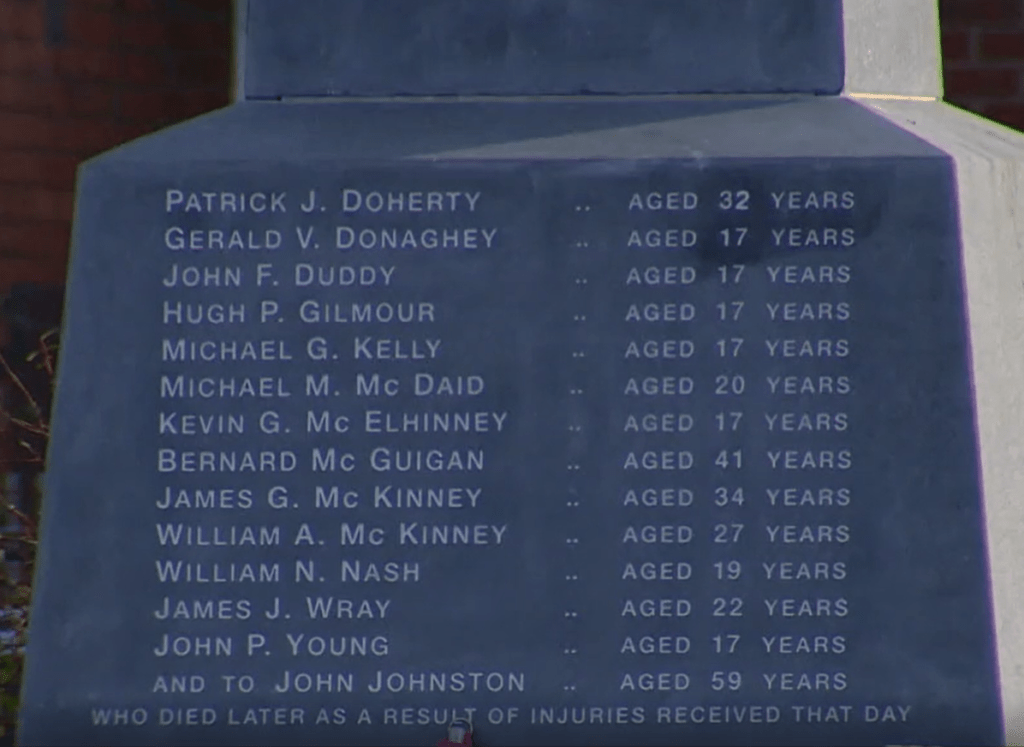

The fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday is today. In Derry, on January 30, 1972, thirteen unarmed people were shot dead by British paratroopers, and another was later to die of injuries. It is one of those events that stands out in the history of the recent Troubles in Northern Ireland, for the massive and enduring impact it had.

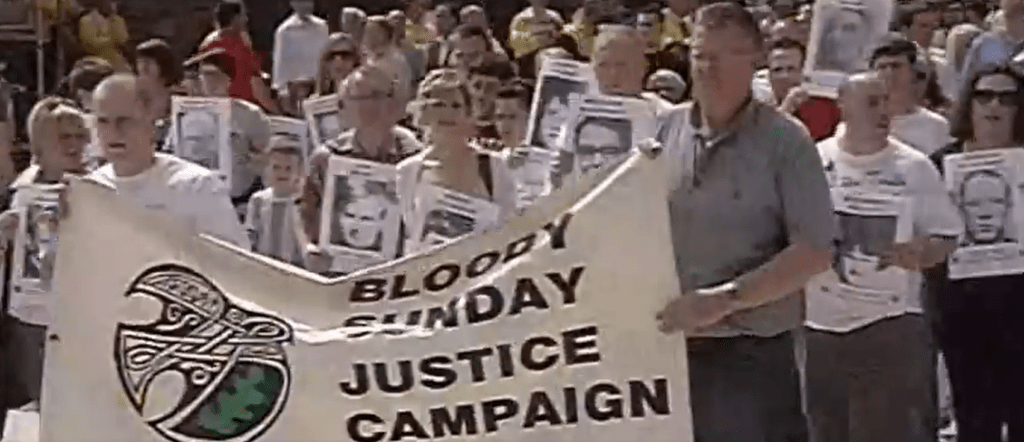

It was an event that has scarred the memory of the people of Derry for a generation and its repercussions, in the decades-long (and unsuccessful) efforts of the bereaved to find some semblance of justice, still reverberate today.

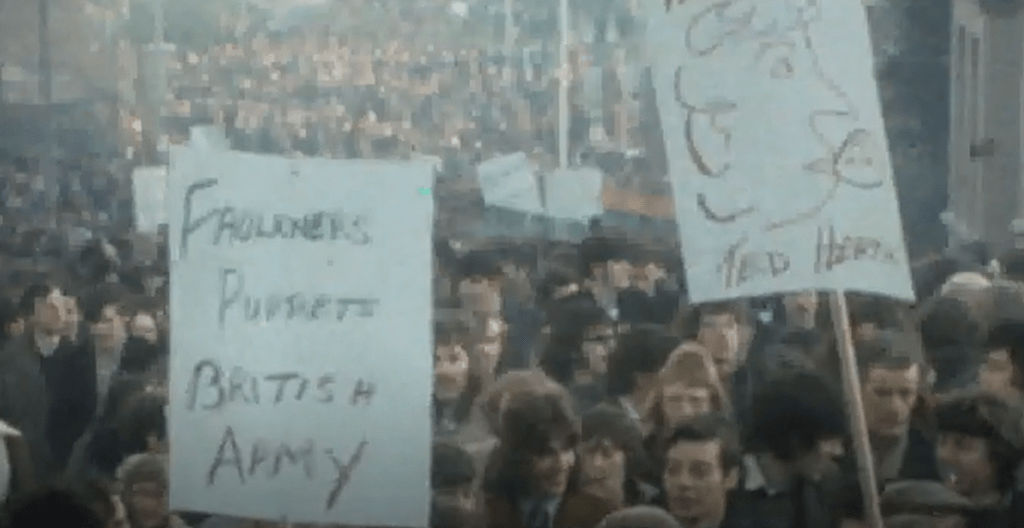

Prior to the demonstration that day in Derry, there had been protests against the introduction of internment without trial the previous August (See article here). On January 22, for example, despite being officially ‘banned’, there had been anti-internment demonstrations in Armagh and in Magilligan, Co Londonderry, where an internment camp had been recently opened.

Some killed trying to help the wounded

The demonstration against internment planned for Derry was one of many and it went ahead, attracting over 10,000, who proceeded peacefully to a rallying point to listen to speeches. It was when a small number broke away to throw stones at the police and while speeches were still being made that British paratroopers began shooting at unarmed protesters.

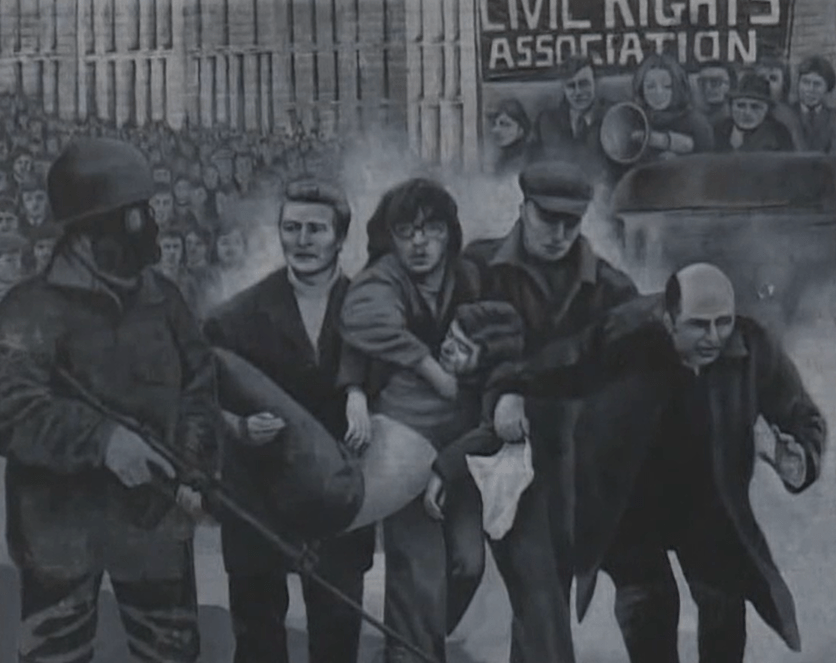

In the ensuing minutes, thirteen were killed outright and many were wounded, one of whom died later. Some of those shot had been trying to help others who had already been wounded. Many of those who died were lying injured or were attempting to escape the firing. Photographs taken at the time show some people, including the Catholic priest who later became Bishop of Derry, attempting to carry the wounded to safety, holding up improvised white flags and appealing to soldiers not to shoot.

The Catholic community throughout the North and South of Ireland was shaken to the core by these events, and numbness quickly gave way to outrage. A week afterwards, a nominally ‘illegal’ demonstration organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association drew more than 50,000 marchers in the town of Newry. This was despite veiled warnings of a repeat of the Derry violence and threats from the police and army of mass arrests.

Speaking in the House of Commons a few days after the events, Bernadette Devlin, MP for Mid Ulster, rose to speak in the House of Commons. “The Minister has stood up and lied to the House”, she said, referring to the Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, “Nobody shot at the paratroops, but somebody will shortly…I have a right, as the only representative in this House who was an eye witness, to ask a question of that murdering hypocrite…”

As uproar developed in the chamber, she ran across the floor of the House, pulled Maudling’s hair and slapped his face. “I did not shoot him in the back,” she said later, “which is what they did to our people.” She resolutely refused to apologise when interviewed afterwards by the press, only being sorry, she said, that she hadn’t got him “by the throat”. (That press interview can be seen on film, here)

British embassy in Dublin attacked and burnt down

The wave of anger in the Irish Republic led to a massive demonstration of 20,000 in Dublin, and the British Embassy was attacked and burnt down, as the outnumbered gardai looked on helplessly. As the Dublin Irish Press commented, “If there was an able-bodied man with Republican sympathies within the Derry area who was not in the IRA before yesterday’s butchery, there will be none tonight.”

It was a very prescient comment. The introduction of internment, aimed exclusively at the Catholic community, although Protestant paramilitaries were active, had already acted as a spur to recruitment for the Provisional IRA. But that was a hundred times more true of Bloody Sunday. In his book, A Secret History of the IRA, Ed Moloney writes, “In the Bogside…young people were said to be queueing up by the hundreds to join the IRA.”

The increase in membership of the IRA and the outrage felt in the Catholic community led to an increase in the number and the scale of IRA operations for both wings of the IRA, all of which to one degree or another back-fired them, while at the same time deepening the chasm between the two communities in the North.

Three weeks after Bloody Sunday, the Official IRA set off a bomb at the Paratroopers headquarters in Aldershot, in Kent, only succeeding in killing an army chaplain, a gardener and five women cleaners. On March 4, a bomb was exploded without warning at the Abercorn restaurant in Belfast, killing two and injuring seventy, mostly shoppers. Being a busy Saturday afternoon, this toll of dead and injured, bad as it was, could have been much worse. Sixteen days later, two car bombs exploded in Belfast killing seven, five of them civilians.

Hundreds of angry mothers marched against IRA in the Bogside

In May, the Officials kidnapped and killed a young Catholic Ranger, William Best, who was home on leave from his unit in Germany, while visiting his family in the Bogside. Such was the anger within the Bogside at this that hundreds of women marched through the Bogside to besiege the offices of the Official Sinn Fein, forcing the Officials to declare a cease-fire.

The Provisional IRA, too, increased their operations, for the first time widely using car bombs. In Belfast on July 21, twenty car bombs exploded in just over an hour, killing nine and injuring more than 130 – mostly passers-by, who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. This day, described in Loyalist tradition as “Bloody Friday”, was a political disaster for the Provisionals, losing them support even among Catholics and intensifying the already bitter alienation of the Protestant community. It was as a result of the political damage caused by this campaign that the Provisionals, also, adopted a cease-fire, although theirs proved to be very short-lived.

For the Protestant community, the increased campaign of the IRA afterwards reinforced their perception that they were a community under siege. Attacks on service personnel, police and especially on business premises and downtown Belfast were seen by the Protestant community as an attack on them and in this way the IRA campaigns exacerbated the sectarian divisions that already existed.

British Prime Minister suspends the Northern Ireland government

The British government, meanwhile, facing international opprobrium and a huge loss of prestige, tried to extricate itself from the position its soldiers had put it in, by suspending the Northern Ireland government. On March 24, Ted Heath announces the closure of Stormont and direct rule from Westminster. This was seen as a ‘victory’ by the IRA, although that had no impact on the number, or the nature of the operations they carried out.

The Heath government also commissioned an inquiry within weeks of Bloody Sunday, eventually leading to the ‘Widgery Report’ which was universally hailed as a whitewash. It selectively picked at evidence and statements to put the blame for the killings on the organisers of the demonstration and unknown gunmen who ‘fired first’, thereby exonerating the British Army. The Widgery Whitewash was never accepted in the community in Derry and after the Good Friday Agreement (and as a part of that agreement), Tony Blair announced a new inquiry in 1998.

The new inquiry began in 2000 and was to last a decade. “Statements were taken from 2,500 people, 924 of whom gave oral testimony. One hundred and sixty volumes of evidence, running to 25 million words were considered, as well as thirteen volumes of photographs, 121 audiotapes and 110 videotapes. The final cost was close to £200m” (Eamonn McCann, War and an Irish Town).

Saville Report lets the military top brass off the hook

The subsequent ‘Saville Report,’ published in 2010, found that all of the casualties had been innocent and that none had been carrying a weapon or offered any threat to soldiers when they were killed. Without exception, the anonymous soldiers who had given evidence to the original inquiry were found to have lied. But as Eamonn McCann points out in his book, the evidence was still manipulated “to let senior politicians and military chiefs off the hook”

While there have been attempts since then – but recently suspended – to prosecute one single paratrooper, named as ‘Soldier F’, the Saville report pointed no finger of blame at, for example, Major General Robert Ford, Commander of Land Forces Northern Ireland, or at Michael Jackson, adjutant on the day to Lt Colonel Derek Wilford, commander of the First Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, the unit which had carried out the killings.

Yet, as McCann explains, the Saville Inquiry had in its evidence a document written by General Ford three weeks before Bloody Sunday, in which he had “declared himself ‘disturbed’ by what he regarded as the soft attitude of local army and police chiefs to the Bogside, adding, ‘I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the DYH (Derry Young Hooligans)…A fortnight later, six days before Bloody Sunday, Ford over-ruled objections to the use of paratroopers by Derry commander Brigadier Pat MacLellan and local police chief Frank Lagan.”

The same paratroop unit had been involved in earlier killings

There was no connection made by the Saville inquiry, either, to the fact that the same unit of troops, 1 Para, had been involved in killing eleven unarmed civilians in the Catholic Ballymurphy area of Belfast six months earlier, a massacre that led to no inquiry, no apology and no prosecutions. In fact, Saville flatly refused to take any submissions or accounts dealing with any earlier events.

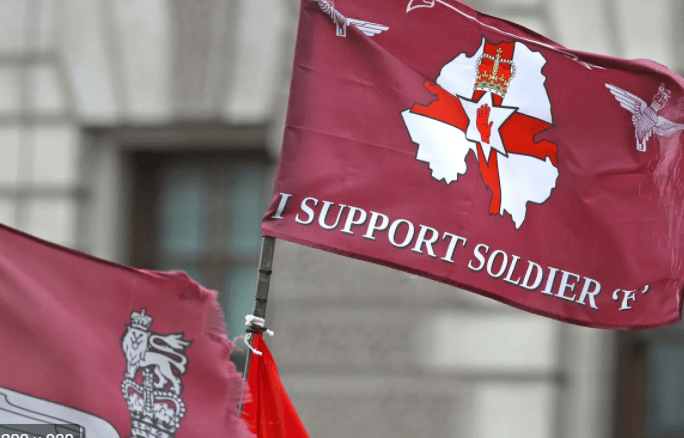

The closest we came to prosecution was the recent investigation into ‘soldier F’, but there was such a campaign in support of him by Tory newspapers and MPs in Britain, that the government announced that he would not face any charges. There were also a number of Protestant bigots in Northern Ireland who took up the case of soldier F, wearing ‘soldier F’ armbands and putting it on banners and murals.

As an aside, but completely relevant to the outlook of the two communities in Northern Ireland now, we should note that to this day, there is a deep resentment in parts of the Protestant community over the time, effort and expense that went into the Saville inquiry. In their eyes it contrasted with what is perceived as much less consideration given to those Protestants who were killed by the IRA, such as those in Enniskillen (12 deaths) in 1987 or in Omagh (29 deaths) in 1998.

British state has always used divide and rule

January 30, 1972, therefore, lives on in infamy in the Catholic community in Northern Ireland. There have been no punishments or sanctions on those responsible for the murders on the streets of Derry that day. It is a measure of how brutal British capitalism can be, even to the extent of murdering its ‘own’ citizens with impunity, if it feels its power, privileges and prestige are under threat.

The central strategy of British imperialism in Northern Ireland, as in other places around the world, has historically been to divide the working class on sectarian lines and to bolster its political control on that basis. That policy was put into tragic and dramatic effect by internment, aimed exclusively at the Catholic population in 1971, and then by the subsequent killings in Ballymurphy and in Derry in January 1972.

Bloody Sunday was a pogrom; it was outright sectarian murder, perpetrated by representatives of the British state on behalf of the British state. But the additional impetus that this gave to the IRA catastrophically reinforced the sectarian division in the North. That division still run deep and wide today and is the single most important issue in Northern Irish politics that socialists and the labour movement still need to address.