By John Pickard, Brentwood and Ongar LP member

Left Horizons had a Zoom discussion recently on whether or not nuclear power should be an element in a socialist energy policy. One of the issues that featured prominently in the discussion was the issue of nuclear waste – how dangerous it was and what ought to be done about it. As a postscript to that discussion, it is worth looking at a long feature in the Financial Times (February 6) specifically on the issue of nuclear waste.

The FT is a mouthpiece of business, but at least it is a serious journal, and it soberly reflects the options facing British and international capitalism in a manner than you would ever find in the tabloids or even pretend-serious propaganda sheets like the Telegraph or the Times.

Reading the FT shows that there is clearly a serious dilemma within governments about what to do with nuclear waste. Some of those difficulties are being particularly played out in France where more than in most countries there is a high reliance on nuclear power.

The Financial Times feature focused on a particular plant called Chooz A, in the far north of France, noting that it has been in the process of being decommissioned for over thirty years. Soon after the reactor was turned off, the French government had the most dangerous materials removed immediately, but even the ‘less dangerous’ material is taking over three decades to remove. As in the UK, many radioactive materials are stored in open ‘cooling’ pools of water, like accidents waiting to happen.

Only a state or a religion will live as long as this waste.

Chooz A is actually only one of six very large nuclear reactors in the process of being decommissioned in France. They are owned, as are all French nuclear plants, by EDF, a state-owned energy company which also operates in the UK energy market. The total dismantling cost will be an estimated €500m, according to the FT, but the issue is not just the cost, the fact that the most hazardous material will remain radioactive for thousands of years. As one of the commentators graphically put it, “Only a state or a religion will live as long as the waste, and maybe not even them.”

Most countries with waste to process have toyed with the idea of burying it deep underground, or even on the seabed, the former being a lot more popular than the latter, not on account of it being ‘safe’, but because it is ‘less dangerous’ than dumping it in the sea.

Deep ‘geological repositories’, therefore, look the likeliest option for managing waste. The aim is to ‘vitrify’ the waste – turning it into something resembling glass, for easier transport, storage and handling – and then finding a hole in the ground that is deemed to be geologically ‘secure’, hopefully for millions of years.

This waste deposit might be typically hundreds of metres underground, beneath formations of rocks and clay, the more stable and hardwearing the better. Finland, for example, is looking at burying its waste in copper tubes 400m under the granite bedrock of Olkiluoto island, a site that is expected to begin operation only in 2023. The problem is so far, as the Financial Times put it, “no one has yet managed to do it.”.

Repositories 500m below ground

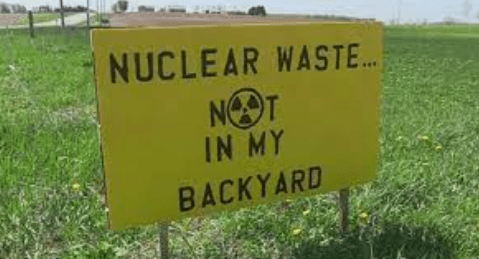

France is currently looking at a deep underground site at Bure, a small town 220km east of Paris. It is proposed that a research facility be created above a web of tunnels and repositories 500m below ground. The project has already cost €2.5bn, but is still not fully active, not least because of the opposition of the local population to having dangerous waste dumped under their feet.

Although France has quite severe waste storage problems, we also have them in the UK. “Sellafield”, the FT article points out, “contains the largest stock of untreated nuclear waste on earth, including 140 tonnes of plutonium”. Plutonium, let us recall, has a half-life of 24,000 years.

“Though the plant was shut down in 2003, it remains the biggest private employer in Cumbria. More than 10,000 people continue to undertake a colossally expensive clean-up that is expected to take more than 100 years and cost above £90bn”.

A partner in a French energy consultancy, explained in the FT article that “Nowhere in the world has anyone managed to create a place where we can bury extremely nasty nuclear waste forever.” Even if the burying of waste in deep-lying hard rock was technically and scientifically feasible, as some argue it is, there is still a serious waste management problem simply being handed on to future generations.

The French government plans for Bure are even looking to offer assurances that the site of the radioactive waste is not ‘forgotten’ a century or two further on. The agency set up by the French government to handle waste, Andra, is considering ways to warn future generations about what lies beneath the town of Bure, “perhaps” the FT journalist adds, “by inscribing microscopic information on a hard disk of sapphire, designed to withstand erosion”. Discussion of waste management in these terms might be reassuring to some people today, but to many it is an alarming admission that we are merely kicking a very dangerous can down the road and dumping it on our grandchildren and their children’s’ children.

After Fukushima, Germany ditched its nuclear energy plans

Across the world as a whole, nuclear waste is a growing problem. Although some countries have turned their backs on it as a means of generating electricity – most notably Germany, after the Fukushima disaster – most advanced capitalist countries are planning to increase their nuclear capacity. Global investment is expected to be $46bn in 2023, up on the previous two years. Even France is building more nuclear reactors.

There are currently 52 nuclear reactors under construction in 19 countries worldwide. That is a lot of waste to be managed. Already, it is believed, there is around a quarter of a million metric tonnes of spent fuel rods spread across fourteen countries, mostly collected in cooling pools at closed-down nuclear plants, “as engineers and waste specialists puzzle over how to dispose of them permanently”.

While the European Commission recently reclassified nuclear power as a “green” industry, making it eligible for “sustainable finance”, there is no serious consideration given by the EU Commission to the huge complexity of European-wide decommissioning after the 30- or 50-year life-span of plants or the even more complex (and expensive) problem of waste.

“Nobody”, the FT correspondent writes, “has yet given a satisfactory answer to the question of what to do with thousands of metric tonnes of high-level nuclear waste, some of which can remain radioactive, and thereby lethal, for up to 300,000 years”.

What is the real ‘efficiency’ of nuclear power?

In looking at the ‘efficiency’ of nuclear power, one needs to consider the costs associated with decommissioning, and the ongoing costs of transportation and storage of waste – and this is only the ‘end’ of the process. Before the nuclear plant is operational – for perhaps thirty or fifty years – there are the costs (including ‘carbon’ costs) of exploration, extraction of Uranium, purification and the construction of the nuclear power station.

Given all these costs, is nuclear power really economical anyway? It is notable that the plans to build Hinkley B nuclear power station include a subsidy, because the cost per Kwh of electricity produced is far above the current market rate of wind and solar energy.

When it comes to the thousands of jobs in the industry, there has to be a firm policy for Labour to protect such employment. An incoming Labour government should be committed to maintaining all of the jobs and that means all of the nuclear facilities at first. But that does not mean committing to new nuclear plants and it does not mean in the longer term having nuclear as part of the mix in a socialist energy policy.

What it should means is that nuclear industry jobs should be protected until such time as there is new investment and new industry in its place, providing alternative and equivalent employment. A socialist policy, therefore, might begin with the legacy of employment, technology and even considerable reliance on nuclear power. But there can be no justification for factoring it into long-term plans for energy production.

There can be no justification for dumping the problem of hundreds of thousands of tonnes of nuclear waste onto future generations, when we ourselves have not come to any conclusions about how to safely manage it.