By John Pickard

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent conflict are a sequel to what was an important historical turning point in its own right – the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. If we want to understand Ukrainian national consciousness today, it is important to look at it through a historical perspective.

Vladimir Putin, to justify his military assault on Ukraine, suggested on Russian TV that Ukraine was a ‘fake’ country, an ‘artificial nation’ that was part of Russia and always had been part of Russia. It is an idea, in one form or another, that finds some echo in the labour movement. It is undeniable is that there are strong historical, cultural and political ties between Ukraine and its larger neighbour to the North. But to suggest that there is no Ukrainian national identity or no Ukrainian national consciousness is completely wrong.

The experiences of the Ukrainian people during decades under Stalinism left bitter memories. There were three years of Nazi occupation, and they were horrific enough, but there were also two periods of mass famines that were a direct result of the policies of dictated from Moscow, the first in the decade before the Second World War and the second in the years immediately following liberation from Nazism.

Ukraine was the ‘bread basket’ of the USSR

This is not the place to go into the reasons for rise of Stalinism after the October Revolution, or to deal in detail with all of the policy twists and turns of that rising bureaucracy in the 1920s and 1930s. But at a certain juncture, from 1929 onwards, the bureaucracy swung dramatically to the ‘left’ and launched a campaign of rapid collectivise of agriculture, which inevitably meant forced collectivisation. This had a dramatic effect on Ukraine especially, which had a large and productive farming sector and was the ‘bread-basket’ of the USSR.

Even Nikita Khrushchev, later leader of the USSR but at that time a Party apparatchik in Ukraine (and an avid supporter of the purges), later admitted in his memoirs that “the Stalin brand of collectivization brought nothing but misery.” On the orders of the Kremlin, military detachments were sent into the countryside to sequester grain and livestock to feed the cities.Even the seed corn for the following year’s harvest was confiscated.

Farmers and their families were literally left to starve. Nearly four million died in an event marked in Ukraine in modern times as the Holodomor, which is commemorated every year.

Neither should we forget the monstrous purges of Stalin around the same period, when the majority of the 1917 Bolshevik leadership were wiped out. Stalin drew a line of blood between his rule and the ideas and policies of the period of Lenin. These murderous purges were visited upon Ukraine even more severely than in other parts of the USSR. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Communist Party members were shot, and untold numbers of non-party workers were ‘disappeared’ or sent to the gulags.

“…deaths from starvation. Then cannibalism started…”

During the wartime occupation, the Nazis broke up the collective farms, and after liberation by the Red Army, the Kremlin for a second time imposed forced collectivisation on agriculture. This was imposed on a population that had barely recovered from the privations of Nazi occupation; indeed, many people were literally living in holes in the ground because cities, towns and villages had been reduced to rubble.

The new sequestrations of grain ordered by Moscow were a knee-jerk reaction to food shortages across the whole of the USSR and once again they led to famine in which millions died. “Soon I was receiving letters and official reports”, Khrushchev wrote, “about deaths from starvation. Then cannibalism started.”

Both the pre-war and the post-war famines affected the entire Soviet Union, not just Ukraine, but in terms of the national outlook of Ukrainians and other non-Russian nationalities, these experiences left deep scars, which lasted for generations. Irish political activists today still refer – and with justification – to the Irish famine of a hundred and fifty years ago, which was a calamity created by British rule. How much more understandable is it, therefore, that much more recent experiences of artificially–induced famines should run through the culture and political traditions of Ukraine?

The costs of the Chernobyl disaster fell on Ukraine

In more recent times, the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 added further to the feeling among ordinary Ukrainians that their interests were not of much concern to the Kremlin. The Chernobyl nuclear facility was managed from Moscow, but it was Ukraine that picked up the bill, in terms of lives lost, exposure to health risks and the cost of clean-up, not to mention the resettlement of thousands obliged to move away from contaminated areas. Four days after the nuclear disaster, Moscow was still insisting on holding the traditional May Day parade in Kyiv, even as the city was threatened by a radioactive cloud. Such things are not easily forgotten.

There were protests at the time of the Chernobyl disaster, although somewhat muted, because they were suppressed. But there have been many others since then, coinciding with the twenty-fifth and then the thirtieth anniversary. All of these events have left their mark to one degree or another in Ukraine and have fed into the national consciousness of the majority of the people.

The opportunity for an expression of national identity came eventually with the breakup of the Soviet union in 1991. By that time, the USSR was in the grip of permanent economic crisis. As Trotsky had anticipated in his writings in the 1930s, the more complex the Soviet economy became, the more the bureaucracy became a barrier to progress. Through the suffocation of democracy, and by corruption and inefficiency, all the advantages of a planned economy were lost. From having been only a relative brake on economic development, the bureaucracy became an absolute brake.

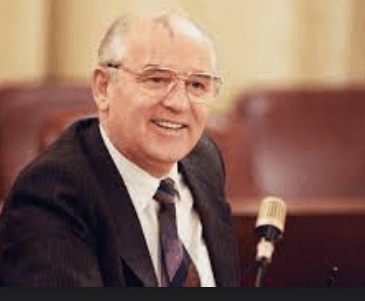

When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, therefore, he sought to find a way out through his policies of perestroika (‘restructuring’) and glasnost (‘openness’). Although they were not meant to break up the Soviet union, an unprecedented degree of openness led inevitably to calls in the Baltic states and Ukraine for greater autonomy within the USSR and then for outright independence outside it. As an aside, the movements of the republics for independence were not fostered by NATO or even foreseen by it, but were a product of the social and economic crisis in the USSR.

Overwhelming vote for Ukrainian independence

The Ukrainian parliament declared independence in August 1991 and called a referendum three months later, on December 1, to confirm the decision. In the event, the result was overwhelming. In a turnout of 84%, an overall majority of over 90% voted for independence. More significantly, the vote in those regions with a higher proportion of the Russian-speakers also voted the same way. In Odesa, 85% votes for independence, in Luhansk 83%, in Donetsk, 77% and in Crimea over 54%. These figures are a crushing refutation of the idea that there was no separate Ukrainian identity.

It is clear that at that time, the language differences between different Ukrainian nationals were a completely secondary issue. That should not surprise us here in the British labour movement, because in the nationalist movements in Scotland and Ireland, language has also played a secondary role. It is a minority of workers in Ireland and Scotland who speak the Irish language or Gaelic Scots, but that does not prevent their self-identification as ‘Irish’ or ‘Scottish’ nationals.

In Ukraine, the referendum of 1991 showed unmistakably the strength and depth of Ukrainian national feeling and a Ukrainian identity across all areas of society. Even today, there are many ‘ethnic Russians’ who consider themselves to be Ukrainian and not Russian, the Ukrainian president, Zelensky, being a case in point.

Since 1991, however, the picture has become more complex. National consciousness is never a fixed or an immovable social organism – it can ebb and flow, depending on social, political and economic developments. The picture in 1991 is not the same as the picture by 2022.

Donbas industrial area reduced to a rust-belt

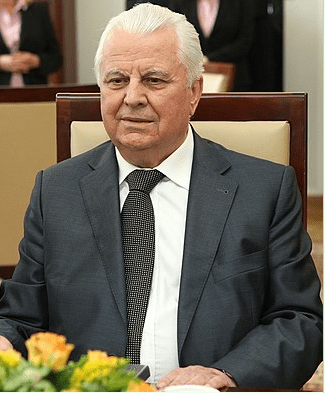

The first president of the new independent Ukraine in 1991 was Leonid Kravchuk, a member of the Communist Party of the USSR and an apparatchik of the first order. But like other leaders in the different republics of the USSR, he could see which way the wind was blowing, and from having been a Kremlin loyalist, he rebranded himself as a national communist, to win the presidential election run simultaneously with the independence referendum. Like other former Moscow loyalists in the other republics, Kravchuk was attempting to channel growing the mass discontent along national lines.

But independence did not solve the economic and social problems in Ukraine. As with the rest of the republics of the old USSR, not excluding Russia itself, Ukraine suffered virtual economic collapse in the 1990s, as the economy was privatised and rich ‘oligarchs’ looted what had been state property and state industries. In the Donbas, there was a complete decline of the traditional industries, and the region became, like its counterparts in Western Europe and the USA, a rust-belt. There was little in the way of new jobs and industries to replace the old ones.

It has been as a result of that economic decay and decline that these areas have become far more disaffected and disillusioned with rule from Kyiv. Just as voters in Hartlepool, Sunderland and Barnsley felt ‘left behind’ in British participation in the EU, having seen little to replace old dead industries, so too many former workers in the Donbas became disillusioned in the promise of independence. There was no ‘independence dividend’ for them, and as a result, some have been more open to the idea of re-unification with Russia.

The Maidan protests of 2013-14, which led to the removal of the government of Yanukovych, has further complicated the national question in Ukraine, particularly in regard to the Russian speaking minority. Many ‘ethnic Russians’ consider themselves Ukrainian and not Russian, but there is probably a higher proportion of Russian-speakers today who have illusions in the idea of re-unification with Russia, and their view will have been reinforced by activities of right-wing Ukrainian nationalists and the downgrading of the Russian language in 2014.

However, even if the question of Ukrainian nationhood has been complicated by the events of the last eight years, many tens of thousands of workers and youth are risking their lives for what they perceive as Ukrainian independence and socialists cannot deny the fundamental idea of a Ukrainian nation or its right to self-determination.