By Michael Roberts

The Russian invasion of Ukraine grinds agonisingly on with more dying and displaced and with further destruction of Ukrainian cities, farms and homes. Back in the major economies, there is another war brewing: the war on inflation.

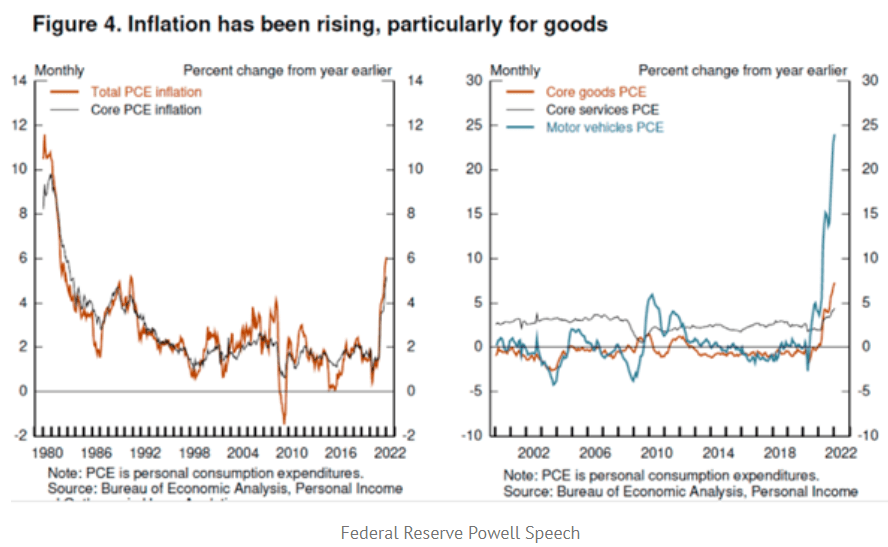

Inflation of consumer prices are now at 30-40 year highs with more to come. The COVID pandemic slump and now the Ukraine conflict have driven energy and food prices up to record highs. The war in Ukraine has gone global. Spiking commodity prices are on track to see their sharpest rises since 1970, sending a shock wave of suffering across the world as the prices of essential goods every human needs to survive are surging upwards. Wheat prices are up 60% since February. Food prices are now higher than during the global food crisis of 2008, which pushed 155 million people into extreme poverty.

And the price inflation in these key areas has migrated into general price increase. Annual consumer price inflation (CPI) now stands at 7.9% in the US, 5.9% in the Eurozone; 6.2% in the UK and even Japan, long a deflating economy, now has an inflation rate of 1%. In the so-called emerging economies, inflation is even worse: India 6.1%; Russia 9.2%; Brazil 10.5%; Argentina 52%; Turkey 54%.

The battle is now to reduce and control inflation and it is being led by the central banks of the major economies: the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. It is the primary job of central banks to control price inflation; not to help to sustain employment and economic growth – they are secondary. (“The ultimate responsibility for price stability rests with the Federal Reserve” – Jay Powell). That’s because inflation is the main enemy of the banking system. Creditors and lenders of money lose out if inflation rises, while debtors and borrowers gain. And central banks were created to support the financial sector and its profitability and not much else.

Central banks have little control over ‘real economy’

And indeed, there is not much else they can do. I have shown in many previous posts the evidence that central banks have little control over the ‘real economy’ in capitalist economies and that includes any inflation of prices in goods or services. For the 30 years of general price disinflation (where price rises slow or even deflate), central banks have struggled to meet their usual 2% annual inflation target with their usual weapons of interest rates and monetary injections. And it will be the same story in trying this time to reduce inflation rates.

All the central banks were caught napping as inflation rates soared. And why was this? In general, because the capitalist mode of production does not move in a steady, harmonious and planned way but instead in a jerky, uneven and anarchic manner, of booms and slumps. But specifically now, because as Fed Chair Jerome Powell put it in a keynote speech to the National Association of Business Economists last week, “Why have forecasts been so far off? In my view, an important part of the explanation is that forecasters widely underestimated the severity and persistence of supply-side frictions, which, when combined with strong demand, especially for durable goods, produced surprisingly high inflation.” Indeed, I have argued in previous posts that, contrary to the view of the Keynesians, the current inflation burst is not due to ‘excessive demand’ or ‘excessive wage increases’ (cost push), but due to the failure of supply/production.

Intractable problems for central bankers

As Powell put it: “contrary to expectations, COVID has not gone away with the arrival of vaccines. In fact, we are now headed once again into more COVID-related supply disruptions from China. It continues to seem likely that hoped-for supply-side healing will come over time as the world ultimately settles into some new normal, but the timing and scope of that relief are highly uncertain.”

And this poses an intractable problem for the central bankers in their quest to protect bank profits. Their monetary weapons will prove useless in this war on inflation. Powell said that “We have the necessary tools, and we will use them to restore price stability.” But does he? As Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, said: “Monetary policy will not increase the supply of semiconductor chips, it will not increase the amount of wind (no, really), and nor will it produce more HGV drivers.”

And Jean Boivin, a former Bank of Canada deputy governor now at the BlackRock Investment Institute, commented: “We are not dealing with demand-push inflation. What we are really going through right now is a massive supply shock and the way to deal with this is not as straightforward as just dealing with inflation.”

If rising inflation is being driven by a weak supply-side rather than an excessively strong demand side, monetary policy won’t work. Monetary policy supposedly works by trying to raise or lower ‘aggregate demand’, to use the Keynesian category. If spending is growing too fast for production to meet it and so generating inflation, higher interest rates supposedly dampen the willingness of companies and households to consume or invest by increasing the cost of borrowing. But even if this theory were correct (and the evidence does not support it much), it does not apply when prices are rising because supply chains have broken, energy prices are increasing or there are labour shortages.

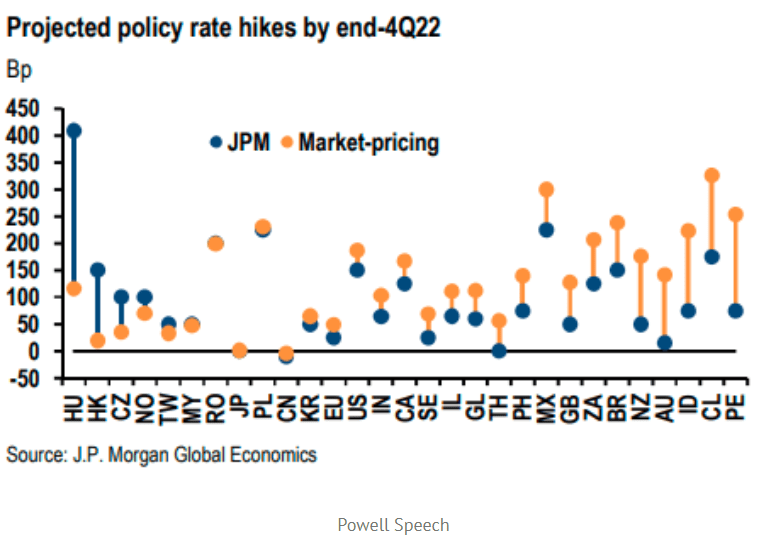

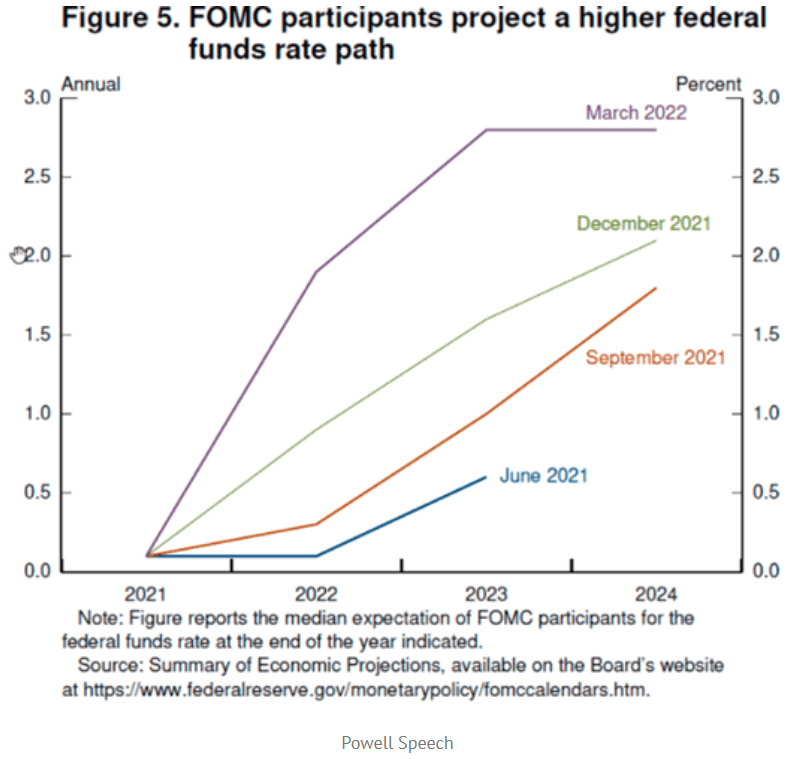

Nevertheless, central banks have only the monetary weapon to apply to accelerating inflation. So the Fed plans a sharp rise in its ‘policy rate’ of interest (the Fed Funds rate), which sets the floor for all borrowing in capitalist markets. And so do other central banks.

Powell aims to hike the Federal funds rate to 1.9 percent by the end of this year and thus rising above its estimated longer-run normal value by 2023.

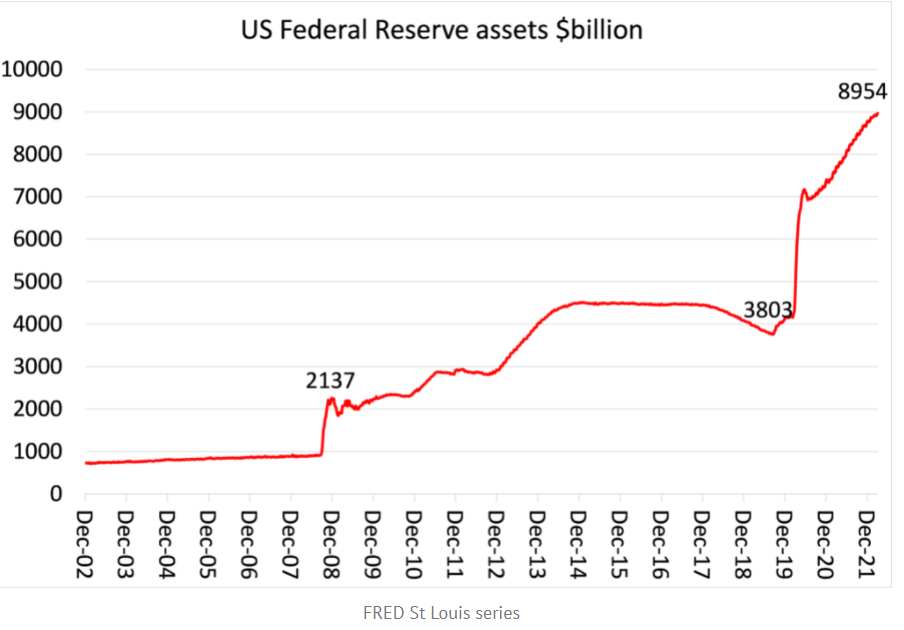

Fed balance sheet jumped from $1tr to $9tr

At the same time, the Fed is ‘pivoting’ on its previous programme of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) ie buying government and government-backed bonds through an increase in money supply. During the 21st century, the Fed has bought so much government paper that its balance sheet has jumped from $1 trillion to nearly $9 trillion, more than doubling during the COVID pandemic.

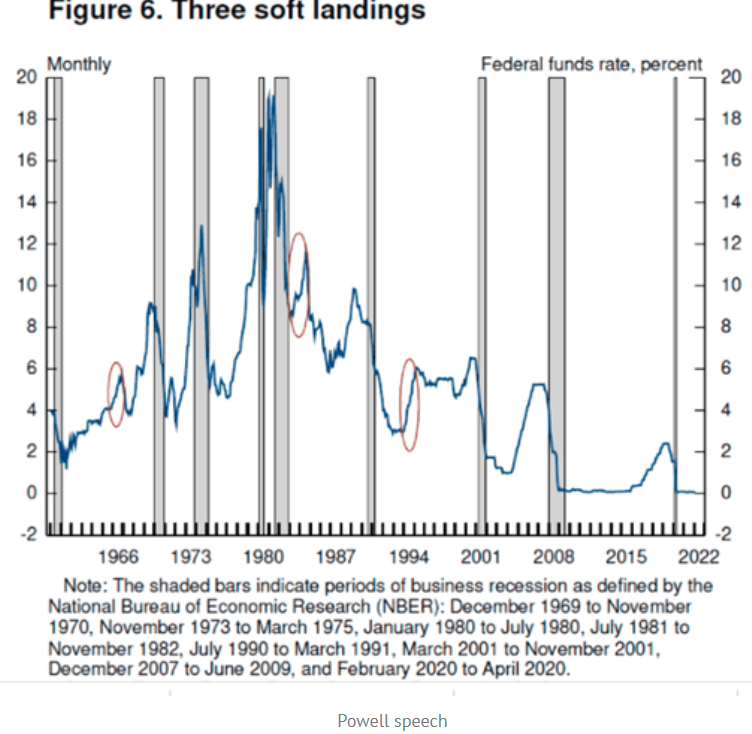

Now the Fed is going to reduce the total amount of the balance sheet. Powell claims that “these policy actions and those to come will help bring inflation down near 2 percent over the next 3 years.” Indeed, there is optimism in mainstream economics that increased interest rates and a reverse of monetary injections by the Fed and other central banks will not only kill inflation but also avoid a slump in investment and consumption as a result, as long the Fed gets on with the war on inflation and ends its policy of appeasement. Powell commented that “the historical record provides some grounds for optimism: Soft, or at least soft-ish, landings have been relatively common in U.S. monetary history.5 In three episodes—in 1965, 1984, and 1994—the Fed raised the federal funds rate significantly in response to perceived overheating without precipitating a recession.”

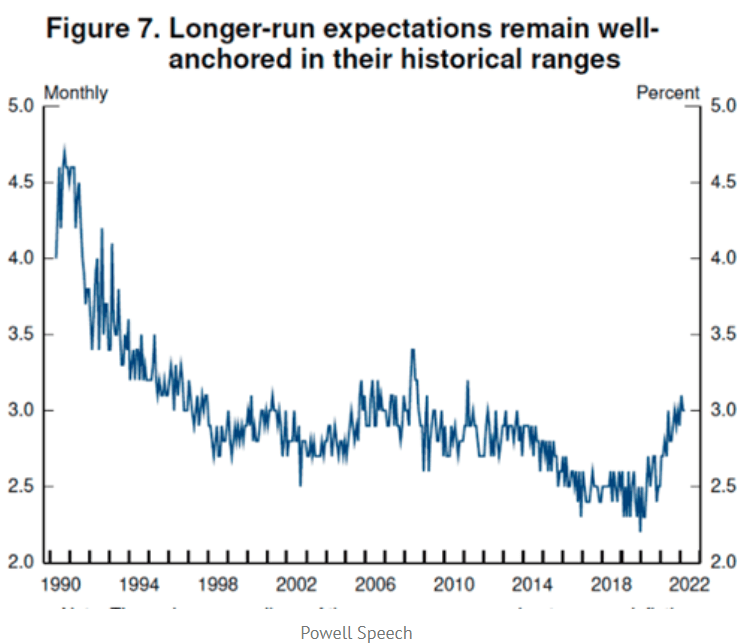

Powell also made much of the current mainstream explanation of inflation: that it is mainly caused by ‘expectations’ of price rises gaining traction among consumers and businesses – self-fulfilling if you like. “In the recent period, short-term inflation expectations have, of course, risen with inflation, but longer-run expectations remain well anchored in their historical ranges.”

This ‘psychological’ explanation of inflation removes any objective analysis of price formation. Why should ‘expectations’ rise or fall in the first place? And as I mentioned before, the evidence supporting the role of ‘expectations’ is weak. As a new paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concludes:

“Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

Powell significantly left out of his ‘soft recessions’ the two deepest and widest slumps in the major capitalist economies since 1945, namely 1980-82 and the Great Recession of 2008-9, when interest rates rose sharply prior to the start of recession. In doing so, he cannot offer an explanation of why tighter monetary policy can have ‘soft’ landings sometimes and slumps other times.

Two things are missing from the explanation

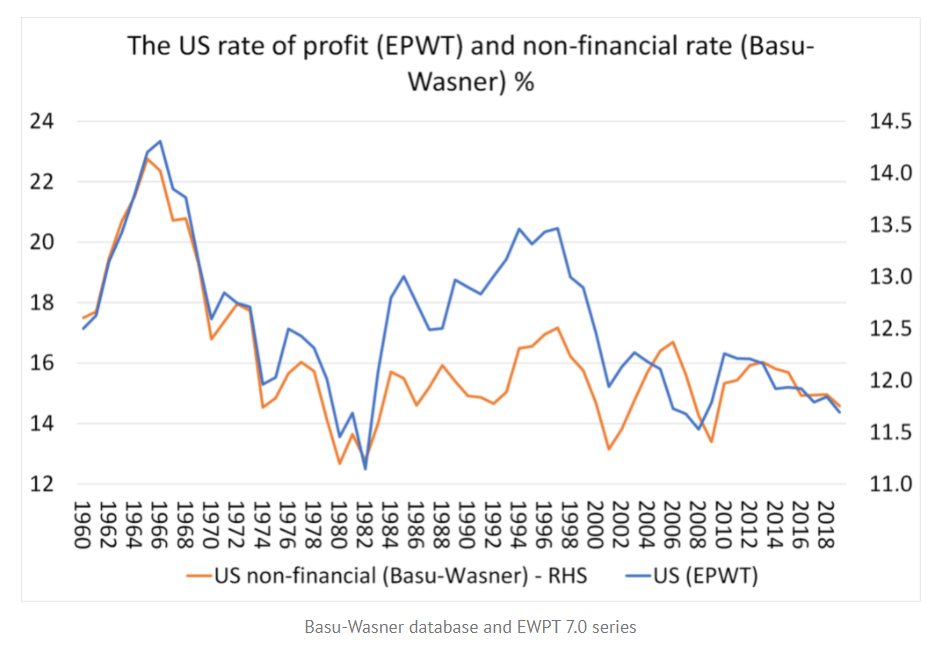

What is missing from any explanation are two things that Marxist theory offers. First, what is happening to the profitability of capital; and second, what is happening to the real rate of interest (after taking into account the inflation rate). In periods where average profitability is high and/or rising, then interest rates can and will rise too but without crushing investment (both productive and unproductive (real estate and finance). That was the case in all the ‘soft’ landing cases cited by Powell.

It was also the case in another optimistic argument for the likely success of monetary policy in controlling inflation. One analyst claims that 1946-48 period is the best historical parallel to now. There were serious supply shortages then leading to sharp rises in price inflation. But eventually price increases slowed as supply came on board as manufacturing switched from military to civil production. The Fed did not have to hike interest rates but just applied a relatively mild reduction in credit growth to shrink its balance sheet. In other words, the market’s “invisible hand” worked. But this explanation again fails to note that average profitability of capital in this period was at 20th century highs, with labour cheap and unused technology to be applied. No wonder supply came on board quickly to douse the flames of inflation.

But that was not the situation in 1980, after the huge profitability crisis that began from the mid-1960s and was exacerbated by the international slump of 1974-5. And it was not that case in 2008-9, where the profitability of productive capital was not much higher than in the early 1980s and much lower than in the 1946-64 ‘golden age’ of capitalist production or even the ‘neo-liberal’ recovery period of the 1980s and 1990s.

Shock hit to borrowing costs

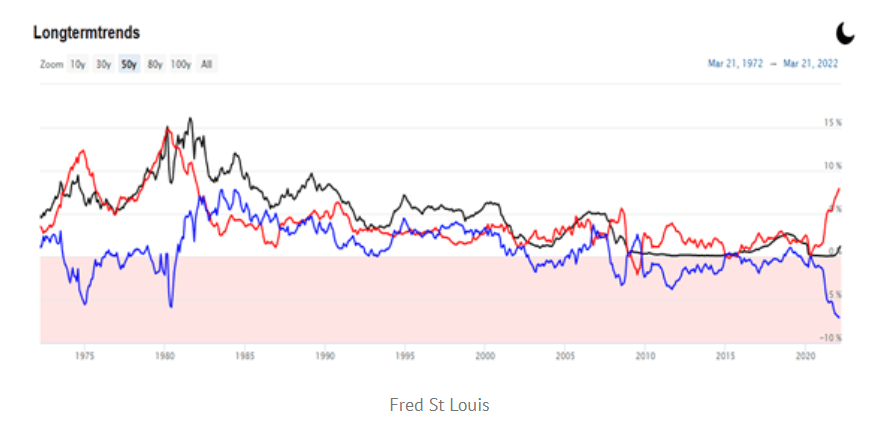

Then there is the second factor, the real rate of interest. Paul Volcker became head of the Federal Reserve in 1979 when inflation rates, triggered by high oil prices and tight labour markets capping supply adjustment (unlike 1948), had reached 20th century highs. Volcker, a convinced ‘monetarist’ and strong advocate of the interests of bankers, immediately hiked interest rates to such levels that real Fed fund interest rate jumped from -3% to +5%. You can see that jump in the graph below, where the red line in the US CPI inflation rate, the black line is the Fed Funds nominal rate and the real rate is the blue line.

This shock hit to borrowing costs in real terms coupled with the very low profitability of capital caused the deepest post-war slump for the major capitalist economies, in two bouts over three years. It was the end of manufacturing jobs in the US, Western Europe and the UK. Productive capital moved to Eastern Europe, Latin America and Asia. Indeed, it was this slump that killed inflation and brought down oil prices, not rising interest rates.

What is the current situation for the real rate of interest? It is even lower than when Volcker took over in 1979. Two things flow from that: to do a ‘Volcker’ and take the Fed real rate into positive territory in order to curb inflation would require a series of Fed hikes not matched in 100 years; and if that were to be applied, given the near post-war low in profitability, it would almost certainly deliver a new slump in investment and production in the major economies – let alone its impact on the so-called emerging economies of the Global South. All this tells you that monetary policy is a crude weapon to control inflation and is not going to succeed without causing a major slump – no ‘soft’ landing.

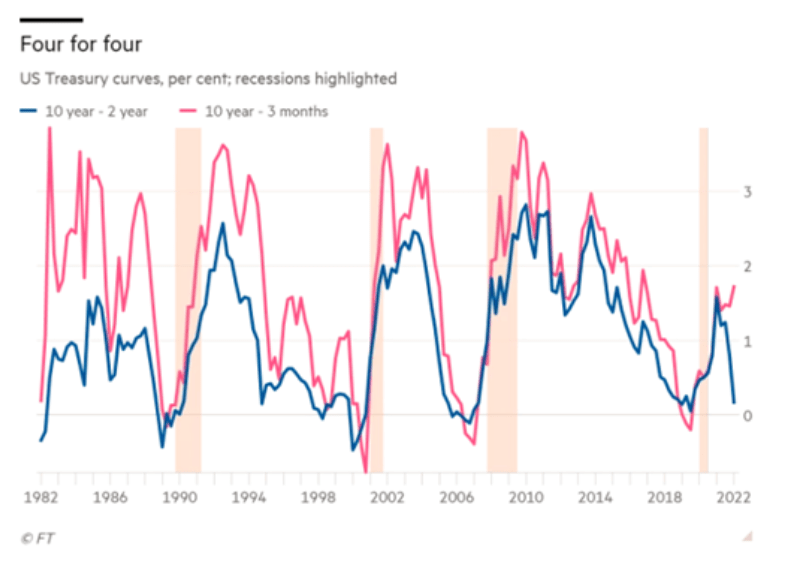

One useful indicator of a recession in the past, which I have mentioned before, is an inverted yield curve. That’s when, in the bond market, the rate of interest or yield on a short-term loan (3m or 2yr) rises above the rate of interest or yield on a longer-term loan or bond (10yr). Normally, if you borrow (issue a bond) for a longer period you must pay a higher rate of interest to the lender or purchaser of the bond because the length of time for the credit is longer and so the loan is subject to more inflation or default risk. But when the ‘yield curve’ flattens or even inverts, a recession usually follows. Why? Because it tells you that purchasers of bonds are getting worried that interest rate hikes will cause a possible slump and so are buying more safe long-term government bonds to protect their cash.

Well, currently the US government bond yield curve is fast heading towards inversion. Jay Powell’s hawkish speech declaring war on inflation led to a sharp drop in the curve. The blue line in the graph below, the 10-year/2-year curve, is barrelling straight towards zero. In the past 40 years, every time that has happened, a recession has followed (as the shaded bits of the chart show). In fact, it’s worse than that: inverted 10/2 curves have preceded the last eight recessions and 10 out of the last 13 recessions, according to Bank of America.

US economy set to slow as the year progresses

Powell tried to dismiss the yield curve indicator in his speech to the NAB, arguing that only the short end of the curve was an indicator of recession and that is when it is falling, not rising: “there is good research by staff in the Federal Reserve system that really says to look at the short — the first 18 months — of the yield curve. That’s really what has 100 per cent of the explanatory power of the yield curve. It makes sense. Because if it’s inverted, that means the Fed’s going to cut, which means the economy is weak.”

Whatever the predictive value of the bond yield curve, the point is that the US economy, the best performer among the G7, is set to slow as the year progresses. There is little room for any further growth through employing more workers, while productivity and business investment is slowing. Year-on-year nonfarm business sector labour productivity advanced only 1% at the end of 2021, down compared with 2.4% in 2020. And business investment was only just 2.4% above pre-pandemic levels at end-2021. Several forecasts now suggest a significant slowdown in economic growth in the US and the UK, and probably an outright recession in the Eurozone before the year is out.

And it is not just the productive sectors of the economy that are at risk. It was the collapse in the housing sector in 2008 that triggered the Great Recession. And after a massive real estate spree during the COVID pandemic, if mortgage rates rise sharply, house prices could turn down, weakening consumer spending. US bond investor Bill Gross commented “I suspect you can’t get above 2.5 to 3 per cent before you crack the economy again. We’ve just gotten used to lower and lower rates and anything much higher will break the housing market.” Mortgage debt as a share of real GDP has already risen 6 percentage points to 55 per cent since the last rate-hiking cycle peaked in late 2015.

There is an alternative to monetary policy

Instead of a ‘soft landing’ as Jay Powell hopes for, Goldman Sachs analyst Philipp Hilderbrand reckons: “Stagflation risk is a real concern today… We are looking at a supply shock layered on top of a supply shock. And the nature of the new supply shock-centred on energy—suggests not only that inflation will move even higher and likely prove more persistent moving forward, but also that growth will take a hit.”

There is an alternative to monetary policy. It is to boost investment and production through public investment. That would solve the supply shock. But sufficient public investment to do that would require significant control of the major sectors of the economy, particularly energy and agriculture; and coordinated action globally. That is currently a pipedream. Instead, governments are looking to cut back investment in productive sectors and boost military spending to fight the war against Russia (and China next).

Which way will it go? Will Powell, Draghi and Bailey be mini-Volckers or will they step back from the conflict and opt for fewer rate hikes and be forced to live with higher inflation? Either way, it suggests that inflation globally will not subside until a new slump emerges, signalling that the central bank war on inflation has been lost.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.