The new, young, left-wing President of Chile, Gabriel Boric, formally took office on 11th March. His election last December was a very welcome piece of good news for socialists in Chile, Latin America and throughout the world.

Gavin O’Toole examines some of the challenges he will now face.

——————————————–

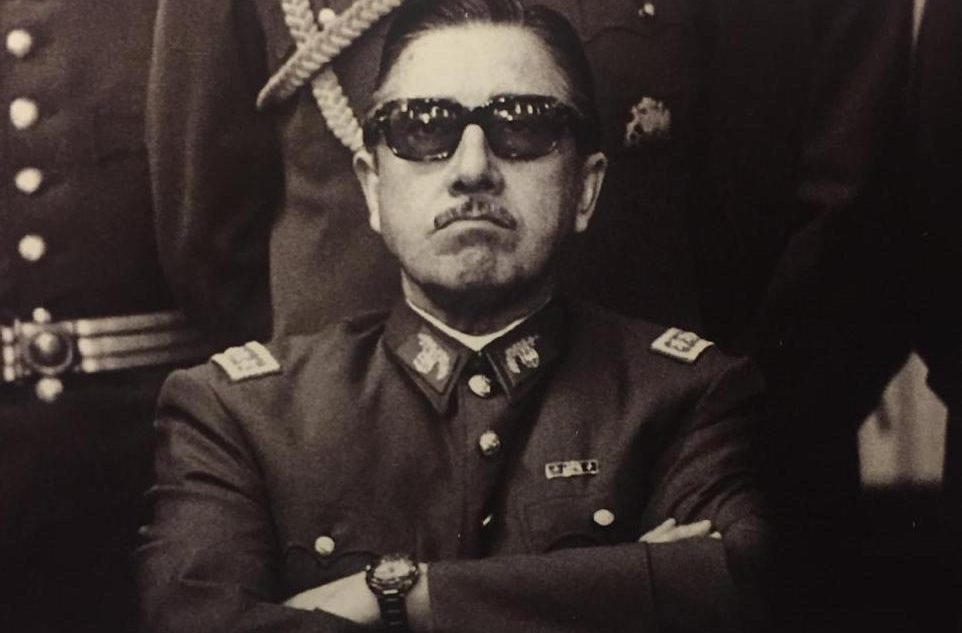

In a brilliant article, 15 years ago, about the grotesque military pomp that followed the death in 2006 of Chile’s brutal dictator Augusto Pinochet, the economist Manuel Riesco asked: is he really dead?

The obvious point he was making was that although the murderous man himself was gone, his main legacy—a hegemonic neoliberal model, benefiting a right-wing elite, manipulating a political system heavily rigged in its favour—remained very much alive.

Echoing a famous phrase that everything in Chile could be expected only “within the possible”, he observed that the country was somehow “stuck in transition”, with continuing exclusion of most citizens from growth and participation despite democratisation.

Writing on the wall

At that time, Riesco argued cautiously that, given a series of mass protests and labour struggles, social movement activism and calls for change in the governing centre-left Concertación coalition, the writing could be on the wall for neoliberalism. Sadly, it would seem his caution was appropriate.

Fear can exercise a powerful veto in politics and nowhere in Latin America has this been the case more than Chile, where Pinochet’s traumatic legacy has persisted to this day like cold sweats following a nightmare.

After the 1990s, there was a fear among progressive sectors that “coup coalitions” would frogmarch in to sabotage a fragile democracy and erase their limited gains. This prompted them to rein in ambitions to challenge the neoliberal order.

A distinct species of stability persisted, based on a de facto arrangement within the political elite that the model and institutions protecting it that were created under Pinochet’s 1980 constitution were off limits.

In short, uncritical acceptance of market forces at the expense of the rights of citizens was the price to be paid by socialists, trade unionists, indigenous groups and progressive activists in order to stay alive!

At first sight, the election of the socialist Gabriel Boric as president, a 36-year-old former student leader and the youngest person to hold Chile’s highest office, offers the best hope of finally burying neoliberalism, something he has rhetorically pledged to do.

Sterile consensus politics

A reader of Marx, he has been variously described as a socialist, a social democrat and a libertarian socialist, and has been critical of Concertación governments that traded places alternately with the right through a long period of sterile consensus politics.

Yet a more critical appraisal both of Boric and the prospects for real change can lead to a more disconcerting view.

Rather than a positive vote for radical transformation, there is little doubt his victory in 2021 reflected the continuation of fear, across a diverse spectrum of “new left” and centrist voters, of a return of fascism embodied by his nemesis, the ultra-conservative José Antonio Kast.

Indeed, the allies Boric picked up along the way are not natural bedfellows and see him simply as the lesser evil – “better than a Nazi like Kast”.

Vote for fear.

This vote for fear is a real problem for the left in Chile, Latin America and internationally because the country retains symbolic importance deriving from Pinochet’s coup in 1973.

As Latin America’s most developed economy, Chile has always been a bellwether by which international capital and its domestic vassals have judged their vision of progress in the region—and the left has judged its limitations.

If Boric fails, faced with an array of opposing forces embodied in the figure of Kast, growing disillusionment with democracy among Chile’s long-suffering masses threatens to exacerbate precisely those social tensions that play into the hands of the far-right.

Those hoping for revolutionary change should not, therefore, hold their breath. Notwithstanding the significance of Boric’s triumph, and high expectations on the left, the results merely underscore just how divided Chile is.

The shadow of 2019

The backdrop to Boric’s victory was what occurred in 2019, when an otherwise trifling increase in subway fares escalated into widespread violent civil unrest across Chile that reflected exhaustion with inequality.

Boric identified with the demands of the demonstrators and promised to implement many of them—from higher taxes to better public services—by creating a more inclusive society.

He was a key player in the effort to halt the violence and, pursuant to a political accord, Chile held a plebiscite in 2020 in which citizens voted to redraft Pinochet’s constitution.

Litmus test

His supporters insist he will transform the neoliberal model inherited from the dictatorship—and this will ultimately be the only litmus test by which to judge his tenure.

Although moderated by Concertación governments through public policies aimed at cutting poverty, neoliberalism represents a hegemonic status quo in Chile. As such, the country has been a laboratory—hailed by capitalists at home and abroad as a successful combination of a market economy and democracy—and hence promoted as a role model for other emerging countries.

Since the days of Pinochet, international capital has been a major protagonist in this story.

Lest we forget, in 1970 the US corporation ITT became an instrument of the CIA to weaken the socialist president Salvador Allende prior to the 1973 coup, and foreign companies funded anti-Allende strikers. Since then, inviting international capital in the form of “Foreign Direct Investment” (FDI) has been a central pillar of Chilean development strategy.

Today international financial institutions laud the fact that Chile is the most “globalised” economy in Latin America—a measure of its embrace of foreign capital and “free trade” (it has signed 30 free-trade agreements). It’s an attractive place to do business, with rules that allow most enterprises to be 100% owned by foreigners. US, Spanish and Canadian multinationals and mining corporations have flocked to take advantage of highly favourable tax regimes.

Multinationals

The role of multinationals in Chile’s economy has always given them considerable influence. A handful, mostly listed on the London stock exchange, control the lion’s share of Chilean copper exports, and dependence on copper is a key pillar of the country’s sustained growth.

As a result, despite repeated efforts to diversify, Chile remains vulnerable to international copper prices. The cost has been a loss of sovereign decision-making over economic policy—with the obvious conclusion that it has been ordinary people who have paid the price.

Another characteristic of this model has been the financialisation of the economy—the commercialisation of social life in which no area of public policy is off-limits to business.

Since the 1980s Chile has had one of the longest and deepest records on privatisation in Latin America, and a case in point is its notorious privatised pension system which has left large sectors of the workforce without effective coverage.

Economic and political inequality

Neoliberal hegemony in Chile is hailed by its proponents as having been a great success because it has achieved favourable macroeconomic results.

But it’s a classic example of competing realities, because rather than distributing the gains of growth across society—the key argument of “trickle down” economics—it has merely produced a few very rich people alongside widespread inequality.

Chile is the most unequal country in the OECD, and GDP is concentrated in a few large, capital-owning dynasties while half of the population survives on the minimum wage.

As the 2019 uprising demonstrated, economic inequality has its political counterpart. Indeed, the political expression of Chile’s model has been a transformation of democratic institutions by elite interests into captive mechanisms to favour the rich.

Scandals

Evidence of this is the money flooding into electoral campaigns outside the legal framework, and ensuing scandals—what some wag has called the “direct democracy of capital”.

The career of outgoing right-wing president Sebastian Piñera—who, while in office, faced allegations of tax evasion, insider trading and bank embezzlement—exemplifies the apparent impunity enjoyed by elites, and hence the influence capital can exert on a weak democracy.

Business leaders have a virtual veto over public policy—just days before the 2019 explosion, the industry federation (SOFOFA) questioned legislative bills concerning environmental protection, reduced working hours, and pension reform that it believed risked economic growth. Let’s not forget that, following Allende’s victory, SOFOFA played a key role in destabilising the economy to create conditions for a coup.

The politics of deadlock

To understand why voters shifted to Boric in the presidential elections, it is necessary to appreciate the scale of the threat from the far-right embodied by Kast, whose win in the first-round sent shock waves through the left.

Kast is deeply tainted by association with fascism, and his rabid anti-communism, religious fanaticism, and authoritarianism runs in the family—his father was a Nazi soldier who escaped to Chile while his brother was a “Chicago Boy” economist who worked for Pinochet.

Kast has assembled a menacing coalition of forces that threaten civil rights and advocate gender-based repression and the persecution of minorities. This comprises elites who want to revive Pinochet’s legacy and also includes ultra-conservative politicians, evangelical fanatics, and security forces.

Against this backdrop, opposition to a transformative left-wing agenda is likely to be intense, while structural obstacles will also be at work.

First, as the parties within Boric’s Apruebo Dignidad electoral coalition are in a minority in Congress, the legislative calculus will hamper his efforts to make structural changes.

Small steps?

Second, to woo mainstream actors to his alliance, Boric has edged towards the centre, emphasizing the need for “responsible” movement forward in “small steps”. Ex-Concertación figures are well represented in his cabinet and will resist radical steps.

Third, Boric has been forced to appease business leaders, noting their “legitimate anxieties and fears” and parroting right-wing rhetoric about the 2019 protests. His input was central to the terms established after 2019 to draw up a new constitution that stipulated a two-thirds supermajority in the constitutional convention to approve new articles—offering a significant veto to elites. This conciliatory attitude has won him both praise and scorn. Critics on the left describe him as “amarillo” (yellow) because of his tendency to avoid confrontation and adopt middle-of-the-road positions.

Fourth, even if Congress were to pass transformative laws, observers believe the conservative constitutional court could then strike them down—a concrete barrier to change that helps to explain popular demands for a new constitution.

Finally, until the congressional arithmetic changes, Boric is faced with an unenviable choice once the new constitution has been ratified in September, having to either implement it by decree or to delay doing so. He is caught between a rock and a hard place: decrees play into the hands of a far-right poised to denounce him as a tyrant à la Venezuela and Nicaragua; while delays will anger frustrated, marginalised classes. Both options benefit Kast.

The international agenda

Alongside these domestic challenges, Boric faces considerable international hurdles, given the country’s dependence on foreign investment and markets.

Predictably, his victory was welcomed by most left-of-centre Latin American governments, although a more muted response was evident in Cuba and Nicaragua, reflecting a gulf between the traditional “Marxist” left and social democrats.

As the mouthpiece of international capitalism, however, the financial press was not pleased.

The Financial Times, a must on every Chilean businessman’s desk, voiced concerns that Boric may be a wolf in sheep’s clothing: “The risks remain high … Investors are nervous, capital is flooding out of the country and the overheated economy will cool down fast next year. These should all be strong arguments for moderation …”

Extremists?

The Economist went further, describing the choice in Chile between Boric and Kast as one between extremists, and the Wall Street Journal was even more absurd, calling Boric’s victory a “hard-left turn” unnerving foreign investors and Chileans with money and property.

There are mixed signals from the US that reveal traditional tensions over foreign policy between government and corporate interests.

President Joe Biden’s administration has restated a liberal-internationalist strategy emphasising tired mantras about democracy and human rights that distinguishes between an authoritarian “bad” left, and a social democratic “good” left—thereby manufacturing a false Manichean division in the hemisphere.

Biden was quick to congratulate his Chilean counterpart, yet US policy remains inconsistent and hypocritical, condemning authoritarian trends in countries that resist US hegemony, while ignoring violations by right-wing leaders in allied countries like Brazil.

In recent decades the favoured mode of US intervention has been economic warfare through sanctions, seeking to lock states such as Venezuela out of the global economy.

Mindful of this, Boric acted swiftly to calm US investors by appointing as finance minister Mario Marcel, the respected head of Chile’s Central Bank. He sent an appeasing signal to the US State Department through his appointment as foreign minister of Antonia Urrejola, who has little time for the Venezuelan, Nicaraguan and Cuban regimes.

Hopes for democratic reform

Nonetheless, there are signs of hope—and much will depend on the outcome of the constitutional convention, which marginalised Chileans see as their only chance of structural reform.

The 2020 vote to redraft the constitution was driven by popular anger built up over 30 years in Chile’s neoliberal hothouse, and elections of delegates to the convention yielded surprising results that broke the stranglehold of mainstream parties. Independents won 35% of the seats and candidates of right-wing parties and the former Concertación fared relatively poorly.

These results underscore a deep and progressive crisis of legitimacy that suggests Chile’s long transition may have finally run its course.

They confirm that their progenitor—the 2019 protests—signalled the exhaustion of politics as normal and reinforced the argument that institutional reform to loosen the grip of reactionary forces is essential to Chile’s democratic future.

Yet they also have ominous implications for Boric if he continues to drift towards the centre in order to provide the hegemonic right reassurances about “stability”.

Delaying essential socioeconomic reforms are not likely to prevent future eruptions of discontent but, on the contrary, could strain Chile’s fragile status quo to breaking point.