The election of Emmanuel Macron as president for another five years will open up a period of turmoil in French politics. But within the British labour movement, much of the discussion around the election has focused on the vote for Marine Le Pen, coming much closer to Macron than she did previously.

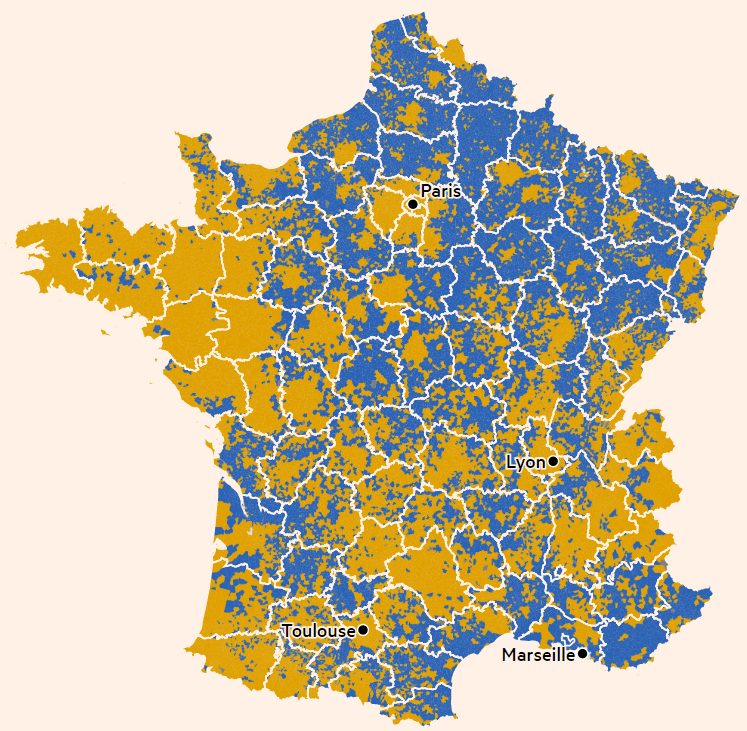

Le Pen got 41.4% of the votes cast, a total of 13.3 million, against Macron’s 18.7 million. This compares with only 33.9% in 2017, when she got 10.6 million votes. It is a sombre warning to the labour movement that the vote for the leader of the National Rally (formerly the National Front) has increased by the best part of three million votes, and it requires some analysis and explanation.

Le Pen herself saw the result to be a huge gain, as will her supporters. “This evening’s result represents in itself a stunning victory,” she said in her concession speech. “For French and European leaders it is evidence of a great defiance towards them by the French people that they can’t ignore, and of a widely shared desire for major change.” (Financial Times).

Le Pen attempted in this election to distance herself from the openly racist past of the former National Front. Her anti-Muslim rhetoric was muted, and it focused far more than in the past on social issues like living standards and the minimum wage. Le Pen will undoubtedly stand for president again and in the meantime, the National Rally will be using the presidential vote as a launching pad for its candidates in the elections to the legislative Assembly, the first round of which is on June 12.

National Rally is not a fascist party

One thing we must make clear is that although Le Pen’s party may have individual members who are fascists, National Rally itself is not a fascist party. Indeed, to describe it as such would to minimise the historical significance of genuine fascism. When Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933, he had a huge paramilitary force at his disposal and within weeks, the cream of the labour movement – socialists, communists, trade union leaders – were in prison camps. The labour movement was completely destroyed within months and that is not something that would have happened in France if Le Pen had won.

The votes for the National Rally leader represent a political development that is not unique to France – it is part of a generalised pattern of votes for nationalist, populist leaders who appear to offer easy solutions to deep-seated social and economic problems. Le Pen is the French equivalent of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage and the votes for her in the former steel and coal-mining areas of Northern France are mirrored by the rust-belt of Virginia and the former coalfields of Yorkshire and the North East of England.

Le Pen’s votes reflect several common international factors. The first is the significant deprivation of a large section of the population. Where once there was a degree of prosperity and certainty, there is now the opposite – a precarious, uncertain economic future, without the comfort of a thriving local industry to offer regular jobs and apprenticeships.

By whatever means one measures the quality of life, it is getting worse, particularly for young people. Decent homes, whether to buy or rent, are more difficult to afford. Health, education, and local government services are all starved of cash by government austerity. For the first time since the Second World War, the older generations are better off than their children and grandchildren and the past seems far more attractive than the future.

Organisations far removed from accountability and control

The second factor that swings votes to the likes of Le Pen is the feeling that events are taking place beyond the control of the ordinary man and woman in the street. There is more than a grain of truth to the idea that their lives are messed about by organisations and institutions far removed from them and unaccountable to them.

Bureaucratic organisations like the EU commission, the World Bank, the European Central Bank and the IMF take decisions that affect the everyday lives of French men and women. These remote institutions seem to move investments, goods and even to allow the migration of large numbers of people from one country to another, without any consideration of the effects on local industries, jobs, services and facilities and for that reason these international organisations are bitterly resented.

The third and perhaps the most crucial factor is the enormous distrust, not to say contempt, that growing numbers of workers hold for the political class. The sharp suits and slick career politicians are all personally well-heeled and immune from impoverishment, but they are also stone deaf to the voices of ordinary people.

It is not that the likes of Farage, Trump and Le Pen – or Boris Johnson for that matter – are themselves poor or downtrodden. Far from it. But they portray themselves, assisted by a friendly press, as ‘different’ to other politicians and politicians ‘of the people’.

It is easy for demagogues like Le Pen, Farage, and Trump under these circumstances, to blame all the ills of society on international trade, on faceless bureaucrats and, not least, on immigrants, for upsetting what had been the past ‘orderly’ lives of working people. The Brexit campaign, with its simplistic slogans of ‘getting back control’ are fruit picked from the same tree that is harvested by Le Pen.

Socialist Party candidates trash workers’ aspirations

Significantly for the labour movement, among those politicians who have been the greatest failures are those from whom workers expected the most – the leaders of the labour movement. In France, Socialist Party presidents offered ‘reform’ and change for the better. But limiting their horizons within the bounds of capitalism inevitably forced them to introduce counter-reforms and cuts instead.

From Mitterand through to Hollande, Socialist Party leaders discredited the party and trashed the aspirations of workers. It was no more than expected this time around, therefore, that the candidate of the Socialist Party got less than two per cent of the vote in the first round and was eliminated.

Although votes for the National Rally represent a deep-seated and confused yearning for genuine change, the distrust of politicians in France applies no less to Le Pen than it does to Macron and all the rest. It was significant that there was a very low turnout in this election, the lowest in fifty years. A huge number of votes were deliberately spoiled.

“In an alarming signal for Macron” France 24 explained, “8.6 percent of those who went to voting stations Sunday also took the trouble not to cast a vote for either candidate, with 6.35 percent of the votes blank and 2.25 percent spoilt. Taken together, these factors mean over a third of registered voters in France did not make a choice in the election“.

This is not the same as simply staying away from the polls, as many did, but a conscious act…actually going along to the polling station and purposefully registering that neither candidate was worth a vote.

Had there been a unified candidate of the left, then there is every possibility that he or she could have won. Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s vote in the first round, had it been augmented by the smaller number of votes for the French Communist and Socialist Parties, and the various ultra-left groups, would have easily taken him at least into second place and the second round. The failure of the left to present a candidate for the second presidential election in a row will open up a profound discussion within the French labour movement.

This may be the most significant election in recent decades, a landmark, even. But that is not only because of the election results per se. It is because the votes are a symptom that France is entering a period of prolonged social and political upheavals.

Tensions are building up in society, and these were evident in the gilets jaunes protests a couple of year ago. At that time, even with the press condemning the ‘violence’ and ‘anarchy of the yellow vests, 70% of public opinion supported them. There is a huge yearning for change in French society, as there is in many countries.

Paris metro and bus strike completely solid

The recent period has seen the longest rail strike in French history, as well as a series of one-day transport strikes in Paris. In the latter case, they have been completely solid, where not a bus or a metro train was moving. Despite winning the election – the first president to be re-elected in twenty years – Macron is deeply distrusted. For publicity purposes he gave the impression of being chastened by the opposition vote. “For French and European leaders”, he said in his victory speech, “it is evidence of a great defiance towards them by the French people that they can’t ignore, and of a widely shared desire for major change.”

But his promises of ‘change’ will turn to ashes. There was relief in the boardrooms of businesses and banks when Macron won: he is their creature above anything else, and his policies will come to reflect that. He is seen as the ‘bankers’ man’, an open defender of capitalism, for example by abolishing or reducing taxes paid by wealthy. His answer to the gilets jaunes was new repressive laws.

Yet Macron’s social base is very narrow; he gained only 28% of the votes in the first round and only won the second because to most workers Le Pen was even more repugnant. It was an unpopularity contest. This will become evident in the legislative elections where Macron may even be faced with having to appoint a Prime Minister of the left, or certainly a political opponent.

For many workers, there is little difference between Macron and Le Pen and that explains the high rate of abstentions and spoilt votes. It was Macron who introduced racist laws directed against Muslims and who raised the bogey of ‘Muslim separatism’.

Over-arching feeling of uncertainty about the future

The past two years of Covid have led to huge social inequalities, as is the case in many countries. There is short-time work, jobs that have been permanently lost, and there is an element of exhaustion within the working class. The overarching feeling across wide swathes of society is a uncertainty about the future. It is the topic of conversation in every shop, but queue and workplace.

Macron’s re-election will not usher in a period of stability or ‘rebuilding’, but one of convulsions, upheavals and social turmoil. French political traditions are far more explosive than those in Britain. The revolutionary events of 1968, where a prolonged general strike appeared, as it were, out of a clear blue sky, was testimony to that. Macron and French capitalism have piled up a small mountain of dry, combustible material and it will only take a spark for it all to go up.

It will be the responsibility of the labour movement to find a way out of the social impasse. Workers’ solidarity, common struggle, and unity around socialist policies will offer a way forward for the French working class. However, the vote for Le Pen, and for other far right organisations in the first round, serve as a warning. These nationalist demagogues, trading in racism, division and conflict will be there to pick up the pieces should the French labour movement fail in its historic task to change society.

See Michael Roberts’ comments on the French election here and an article from La Riposte here.