By Andrew Ford (Warrington South CLP member)

May is the 170th anniversary of the publication in Britain, in 1852, of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Despite being the second bestselling book of the 19th century (after the Bible!), and also a passionate denunciation of the evils of slavery in the South of the USA, it is now rarely read or taught in schools, and is deemed “too controversial” to be made into a Hollywood film. But why?

Who was Harriet Beecher Stowe?

Harriet Beecher Stowe was a committed slavery-abolitionist from New England, who helped runaway slaves to reach freedom in Canada. From the runaways, she gained first hand information on the horrendous treatment of enslaved people – such as selling children separately from their parents, whipping rebellious slaves literally to death and, if they escaped, hunting them like prey.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin also seems to be informed by her grief at the early death of her own child in 1849, as there is a repeated theme of bereavement and the loss of children. Those passages are written with real feeling. She explained her motives in a letter. “I wrote what I did because as a woman, as a mother, I was oppressed and broken-hearted with the sorrows and injustice I saw – because as a Christian I felt the dishonor to Christianity—because as a lover of my country, I trembled at the coming day of wrath.”

The Story : Eliza and Tom

The story begins with her hero, Tom, living a peaceful existence on the Kentucky farm owned by Mr Shelby. Although enslaved, he has a marital home, responsible work and enough to eat. But unknown to him, his owner has fallen into debt and is about to sell him to a slave trader, to be taken south and worked to death on a plantation.

In a chilling moment, the trader, Haley, also sees Harry, a talented black boy of about 4 years of age, singing and dancing. He forces Mr Shelby to sell him the boy to make up the remainder of the debt. Eliza, the boy’s mother, overhears all this and rather than bear the irretrievable loss of her son, she resolves to flee to Ohio, a neighbouring state where there is no slavery.

This sets the structure of the book. with Tom sold down the river to ever-increasing cruelty and misery; and Eliza fleeing north to freedom.

In the first stage of Eliza’s journey, she crosses the fragile ice on the Ohio River, holding her boy in her arms, all the while being pursued by slave catchers – vile people, the dregs of society – who pursue escaped slaves, or else abduct free black people, in the northern states. To do this they employ brutal force, fake legal documents, guns and dogs. In Eliza’s case they eventually decide not to use the dogs “to preserve her looks”.

Another evil exposed

This is another evil that Harriet Beecher Stowe exposed, within the prudish limitations of the time – the sexual enslavement and rape of black women and girls. This was an inherent part of the slave system, which everyone knew about but which was passed over in hypocritical silence. There are constant references from the slave traders and owners to the attractiveness of their female slaves and the premium price they could achieve.

Eliza is sheltered by Quakers in Ohio who help her move north, although there is an armed standoff with the slave catchers on the way.

Harriet Beecher Stowe used this part of her story to expose the infamy of the Fugitive Slave Act which made it a criminal act to help runaway slaves – even in the ‘free states’ where there was no slavery. Under the Act, the southern plantocracy were trying to force all citizens in the north into active support for their vile slave system.

Another iniquity in the Act was that slave catchers could apply to a court and simply claim that a black or “mixed-race” person was actually a slave, owned by someone in the south. The alleged slave could not even speak in their own defence. In this way hundreds of free black people were kidnapped and sold into a life of brutality. This is described in the book “Twelve Years a Slave” by David Wilson, based on the life of Solomon Northup and subsequently a 2013 film: (see here)

Tom ‘sold down the river’

Meanwhile Tom begins his journey down the Mississippi. He begins on a steamboat where a horrifying incident occurs. A black woman comes on board believing her master had sent her to the next town to work as a cook. But once on-board, Haley, the slave trader reveals that he has, in fact, bought her and her toddler son behind her back. He produces a bill of sale to confirm the purchase.

And then, in a further twist, he sells her infant son separately to another passenger on the boat and steals the boy while she is asleep – out of purported humanity to spare her the pain of separation!! Faced with this unbearable loss she throws herself into the river and drowns, leaving the trader cursing the loss of his “purchase”.

Tom himself later rescues a young white child, Eva St Clare, who has fallen in the river and this leads to his purchase by the girl’s family.

A good slave owner?

This allows Harriet Beecher Stowe to examine whether there could even be such a thing as a good or humane slave owner. St Clare, Tom’s new master, can see the evil of slavery but passively accepts it. He forbids whipping or striking of his slaves and will not send them to the ‘caboose’ for punishment despite frequent requests from his wife. The caboose was an abhorrent institution where slaves could be whipped – for a fee. Owners could send them there rather than go to the trouble to do it themselves!

But despite the absence of slavery’s very worst aspects, the slaves are still not free. Tom must work without pay and endure separation from his wife, home and family. ‘Mammy’ is an enslaved black woman employed as a nurse for Eva while pining for her own children who she has not seen in years. And when St Clare dies, his household slaves are sold at the auction block in lots, not knowing what their fate will be – domestic service, sexual abuse or plantation labour.

While waiting to be sold, they are sent to another vile institution, the slave warehouse, where enslaved people were kept ready for auction. At the auction we again see a mother separated from her son, never to see him again. “They don’t feel as we do” was the refrain from the apologists of slavery and Harriet Beecher Stowe destroys this racist idea over and over in the book. Tom is purchased by the brutal plantation owner, Simon Legree, and is taken in chains up the Red River to Legree’s marshy, miserable and badly kept plantation.

Life on the plantation is akin to a concentration camp. The slaves are worked all day under the threat of the lash wielded by two enslaved overseers and any failure to pick enough cotton is brutally punished. At the end of a 12-hour day, the slaves must crowd into rickety cabins and fight to grind cornmeal to eat, only to fall asleep exhausted before the next day’s labour. And every now and then Legree, drunk, will punish one of his slaves just because he can. He has absolute power over them and the slaves share horror stories of past cruel killings of recalcitrant slaves.

Tom refuses to cooperate and insists on helping the others, and for this he is punished with increasing severity until, ultimately, Legree has him literally whipped to death. It is perhaps this part of the book which has led to most criticism. Harriet Beecher Stowe shows Tom enduring his treatment with barely a protest – let alone resistance. But, as a devout Calvinist, her model for Tom was Jesus enduring crucifixion, however unrealistic this is. He is supposed to be a Christ-like figure. Like so much else in the book, her attitude reflects the time in which she was writing, and her place in that society.

Criticism – and wild success

Critics have said that Uncle Tom deals in various stereotypes of black slaves – Tom, the loyal servant; Eliza, the light-skinned girl, menaced by sexual predators; the dark-skinned nanny; Topsy, the mischievous slave-child – and this is true. But it is also true of the white characters – Miss Ophelia, the uptight New England spinster; Marie St. Claire, the swooning southern belle; Eva, the perfect blonde-haired child – and unintentional racism is expressed in all of this.

But it was not Harriet Beecher Stowe’s intention to write a complex psychological novel. Indeed, Charles Dickens shares many of the same faults of stereotypical characterisation. Her intention was to write a book that people would actually want to read; a book that denounced slavery; and a book that made white readers see the slaves as people with feelings, hopes and aspirations.

In this she was wildly successful. Special printing presses had to be commissioned to satisfy demand and hundreds of thousands of copies were sold. In Britain, 1.5 million copies were sold in one year. Uncle Tom was popularised with magic lantern shows across the United States, and her work was pirated into hundreds of plays and dramatic performances. It became the bestselling novel of the century. She had reached her mass audience, and created mass sentiment for abolition.

The slave owners’ reaction: the ‘anti-Tom’ movement

In the southern states, the reaction of the plantocracy was fury. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was actually the first book to be banned by any state in the USA. The hired hacks of the planters denounced her in newspapers as an out-of-touch New Englander who had never seen the reality of slavery; as an inciter of rebellion; and as a woman writer of ‘slush and sentiment’.

Over thirty ‘anti-Tom’ books were published with titles like “Aunt Phillis’s Cabin” or “Uncle Tom’s Cabin AS It Is.” In reply, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote her “Key to Uncle Tom” (here) where she explained and substantiated the real-life basis for her characters and incidents in the book.

In the Jim Crow era, as the former planters rolled back the gains of the Civil War they returned to the attack on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but this time by subverting it rather than trying to destroy it. The ‘Tom shows’ put on across America in the early 20th century portrayed him as a subservient and cringing figure who almost colluded in his own slavery, and showed black people in general as inherently inferior, needing either guidance or control. It was this distortion, which did have a basis in the flaws in the book, that later activists reacted against.

‘Uncle Tom’ as an insult

‘Uncle Tom’ first began to be used as a term of abuse after WW1 when black activists grouped around the ‘Chicago Defender’ and the Marcus Garvey movement began to decry southern blacks moving to the north for being too accepting of racism and too subservient. One war veteran, RP Roots, wrote to the Secretary of War to say it was the time of “The NEW Negro, and NOT of the ‘Uncle Tom’ class, the passing of whom so many white citizens regret“. He wanted equality and desegregation, not just abolition.

Times had moved on, but it was at least in part because of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Ironically, at the same time, the racist ‘Daughters of the Confederacy’ were still trying to get performances of Uncle Tom’s Cabin banned because it “slandered the South”.

In 1949, the leading black writer, James Baldwin, attacked Uncle Tom’s Cabin as doing more harm than good in his essay Everybody’s Protest Novel and by the time of the civil rights movement, the term ‘Uncle Tom’ was a handy shorthand for black sell-outs. But it was only true of the later, stage versions, of the character, not the original Tom of the book, who chose to be whipped to death rather than reveal the whereabouts of two runaways.

A book that helped to change history

Harriet Beecher Stowe had no control over pirated dramatisations of her book. The book itself is well written, in terms of keeping the reader turning the pages, and despite her vision of the slaves being influenced by the stereotypes of the period, she did see them as equal and deserving of freedom. She showed her readers how the slave system rested on cruelty and brutality pure and simple. Her passionate abolitionism found a mass national and international audience through Uncle Tom – it was even recently revealed that it was one of Lenin’s favourite and formative books!

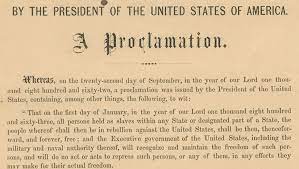

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a book which can truly be said to have helped change history. Eleven years after Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and slavery was ended, but not through Christian meekness but by force of arms.