By John Pickard

This book, long-listed for the Booker Prize in 2020, provides an interesting and moving perspective for anyone interested in the Palestinian/Israeli conflict. It is based on the real-life tragedies of two fathers, one Palestinian and one Israeli, who lost their daughters, one blown up by Palestinians, the other killed by an Israeli soldier.

The Israeli girl, Smadar, was killed by a suicide bomber in a street in Tel Aviv, turned, in her father’s words, into a “scattered human jigsaw”. The Palestinian girl, Abir, was killed by a rubber bullet fired at point blank range to her head by an Israeli Border Guard. Neither of the girls were involved in any political activity or protest: just teenage girls doing what they do: socializing with friends and buying sweets on the way to school.

The book describes how Rami Elhanan and Bassam Aramin followed different paths but arrived at the same point – against the Israeli occupation of Palestine (which goes without saying in Bassam’s case), but also genuinely attempting to understand the ‘other’ community and its history.

Hundreds of seminars and events around the world

Even before the death of his daughter, Bassam became a close friend of Rami – the two addressing each other as brother – and they made it their lives work to campaign for ‘peace’. The later death of Abir did not break that friendship but cemented it more firmly. They travelled the world, often together, invited to hundreds of seminars, meetings and events, to tell the stories of their daughters.

Both were well aware of the role of the US government in propping up Israel and therefore supporting the occupation. Meeting Senator John Kerry on one of his tours, Bassam handed him a photograph of his daughter. “I’m sorry to tell you this Senator”, he told Kerry, “but you murdered my daughter”.

Rami had served with distinction in the Israeli army in three wars, but after a long period of reflection following his daughter’s murder, he came to the correct conclusion that the occupation and Israeli policy towards Palestine was a road leading only to disaster.

Bassam’s history was very different. He had served seven years in an Israeli prison and while inside was the leader of the Fatah prisoners. It was his experience in prison that led him towards a serious attempt to understand his tormentors. He began to study the history of the Jewish people, and the Holocaust in particular. He ended up in a meeting of an Israeli/Palestinian peace group, where he became acquainted with Rami.

This book is named after an imaginary shape, an apeirogon, which has an infinite number of sides, and the book attempts to look at the conflict in Israel/Palestine through its many lenses and complexities. Written in a thousand chapters, some only one sentence in length, the book wanders over many aspects of life in Israel/Palestine, including even its wildlife, its geography, terrain and climate. But above all, it delves into the social issues, including cameos from the history of the Holocaust, including episodes in Nazi camps and stories of survivors and some who did not survive.

However, other than these insights into episodes during the Holocaust – still very revealing in themselves, in all their horror and poignancy – there is less to learn from the book about life among the Jewish population in modern Israel. One gets the impression that the ‘dissidents’ who support ‘peace’ and oppose the Israeli occupation of Palestine are more numerous than they are given credit for, certainly in the western press, although that is difficult to gauge.

Daily humiliations indignities heaped on Palestinians

Where the book is particularly revealing is the way it catalogues the daily humiliations of the Palestinians under occupation. Apart from the murder of Bassam’s daughter, a horrific enough event in its own right, every day, every journey and every activity in the West Bank carries a risk of a dangerous and possibly deadly interaction with the Israeli military. It is impossible to travel anywhere without this risk. Indeed, Abir may have even survived the rubber bullet impact to her skull, had the ambulance carrying her to hospital not been needlessly held up by Israeli Border forces for hours.

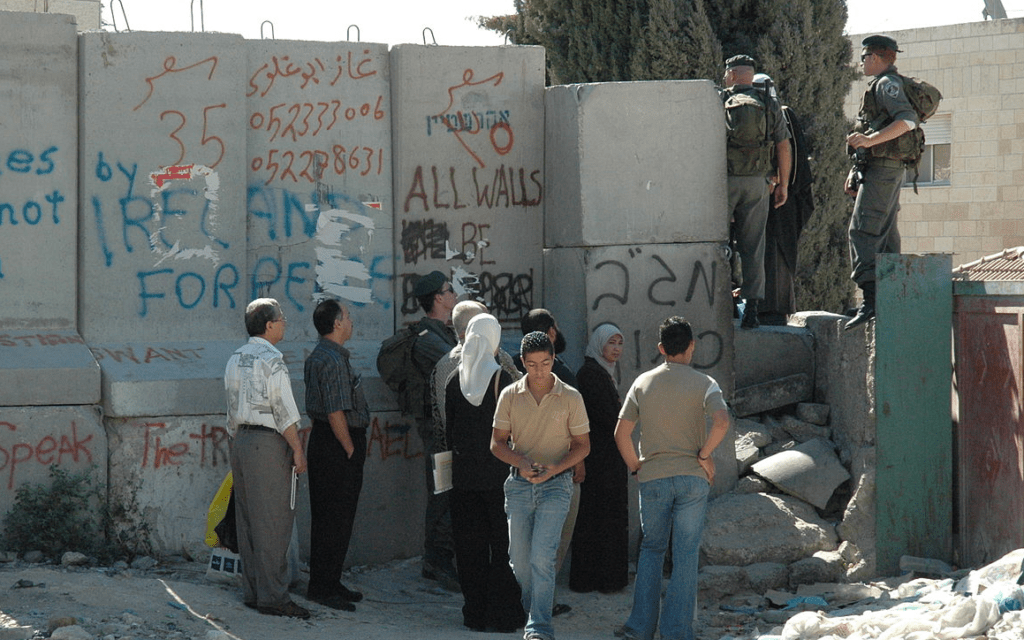

It is not normally good practice to quote at length from a book being reviewed, but one ‘chapter’ is particularly revealing. Using a hidden device, a recording was made of the exchanges between Palestinians and Israeli Border soldiers at a crossing point between Israel and Palestinian territory. The pedestrian check-point in question has turnstiles, so those trying to cross often have to wait a long time in the hot sun. The recording gives a glimpse of the everyday arrogance and casual insults coming from the Israeli soldiers, always, of course, with the implicit threat of violence. This is ‘normal’ life for Palestinians.

“What’s your problem? Step behind the line, please. Not my decision. Whose wedding is it? Her fever’s one hundred and three. I came through an hour ago. I promise I won’t. Speak up, I can’t hear you. Lift it. Your vest, too, asshole. How long have you been working there? Step behind the line. Not without a permit. My classes start at nine. Back please, back. Take off your veil. Door on the left. Next on line. It’s out of date, sorry. Next on line [unintelligible] watermelon. Next on line, hurry up. Turn the handle. God preserve us. Go to the office over there. You’re trying to tell me you work there? What am I, a goat? The funeral’s at ten. Am I your problem solver? I was there for three hours. What do you mean, you don’t know? Spell it for me.

“He took the jeep across. I am begging you in the name of God, just let the boy through. Feet behind the line. Every knot can be untied. He’s sixty-seven, what’s he going to do? It’s not my call, ask my supervisor. I’m not shouting, you’re shouting. Open the zip. I put it in the drier by mistake. What did you say his name was? A leopard doesn’t change its spots. A permit is a permit. I never saw her before in my life. I’m telling you, she’s a twin. I don’t care if she lives in Outer Mongolia. In the next world too. I won’t tell you again, take it out of the plastic please. Just doing my job. Who packed your case? I won’t repeat my question. I need the original. It’s not a [unintelligible] dishcloth. I cut myself shaving. My son-in-law works there. Be sure to send a lazy man. What curfew? It says it right there. My father borrowed it by mistake.”

Palestinians live their daily lives under an iron heel

And so on. There are many interactions reported between Bassam and the Israeli occupation forces, in which the Palestinian man is a model of patience. He has learnt by bitter experience how best to deal with the daily harassment: where to put your hands, how to stand, how to avoid eye contact and so on. On one occasion, when he gets home after a meeting of the peace group, he tells his wife that he had been held up at a check-point, but it was only a “one cigarette-stop”, meaning he wasn’t kept waiting for hours.

In their review of the book, Al Jazeera was critical of its attempt at ‘parity’ between Israelis and Palestinians and they have a point: that is the danger with books that are based entirely at a ‘human’ level. The two grieving fathers in that sense have a kind of ‘parity’, although when I read the book, I never lost sight of the differences in the deaths of the two daughters. Bassam’s daughter, Abir, was killed by a gratuitous act of violence from an Israeli Border Guard while on her way to school, whereas Rami’s daughter, Smadar, was killed in a desperate suicide, in what the bombers no doubt thought of as a means of ‘resistance’.

There is no parity in that sense, nor in the sheer numbers of deaths involved. Israeli civilian deaths at the hands of Palestinians are a relative rarity and where the perpetrators are caught they are dealt with brutally, sometimes even with summary execution. Most Israelis, therefore, can go about their daily lives as people would in London or Paris.

No ‘parity’ between the oppressed and the oppressor

But deaths of Palestinians on the West Bank (and Gaza), including many children, are an everyday event and the Israeli miliary perpetrators, even when they are known, are treated with impunity, as was Abir’s murderer in the book. Palestinians go about their lives as a population under an iron heel. There can be no parity between the oppressed and the oppressor.

In the acknowledgements, the author Colum McCann thanked the two families, whose experiences make up the foundation of the book. Two fathers are united in grief and campaign tirelessly in Israel and beyond for an end to the occupation and for peace.

For activists in the labour movement the book has its limitations. Being a presentation at a human and personal level, it does not deal with broader political issues like policies and perspectives. But neither is it an argument against Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS), or a contradiction of the fundamental historical fact of a state founded by settlement from outside in a land previously occupied by others. Nor does it deal with the kind of class movements or a united movements of Arabs and Jews that socialists would argue is necessary to break the political log-jam in the region.

The first Intifada (1987-93), a spontaneous uprising of Palestinians, had a big impact on the Israeli population, precisely because it was a mass movement and not a desperate act of individual terrorism or the launch of a blind rocket into Israel. The peace movement in Israel was given a huge impetus also by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, particularly when it resulted in the massacres of Palestinian old men, women and children (non-combatants, the Palestinians militias having been evacuated) in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. That provoked mass outrage in the West Bank and massive opposition in Israel.

Overall, the book educates and informs, through hundreds of little episodes and events, and especially about what life is like for Palestinians in the West Bank. The book may not be offering solutions – that was never its intention – but at a very human level it at least points in a hopeful direction and in my opinion, it deserves to be read.

An interview with Rami Elhanan and Bassam Aramin with Colum McCann can be found here.