By Mic Craig in Northern Ireland and John Pickard

Fifty years ago, on July 21, the IRA detonated more or less simultaneously 20 bombs in Belfast, killing nine people and injuring 130. This event is marked in Northern Ireland – at least among Protestants who saw themselves as the targets of the bombings – as ‘Bloody Friday’

But it would be a mistake to imagine that Bloody Friday happened out of a clear blue sky. In the Summer of 1972, Northern Ireland was being torn apart by sectarian killings at an ever-increasing rate. From January onwards, when thirteen unarmed civilians were killed in Derry by the British Army on ‘Bloody Sunday’ (see article here), sectarian murders multiplied.

The Derry murders led to hundreds of young people joining the IRA and in the following month, February, both wings of the IRA killed seventeen people, seven of whom were soldiers and the rest innocent civilians, including seven civilian workers at the headquarters of the Parachute Regiment in Kent.

While the Catholic community saw the Derry killings as a signal that any Catholics were ‘fair game’ for the Army, the stepping up of attacks by the two newly-strengthened wings of the IRA (Officials and Provisionals) created a feeling in the Protestant community that they, too, were ‘fair game’ for IRA attacks.

Protestant paramilitaries organising on a large scale

It was around this time that the IRA exploded its first car bomb, containing a hundred pounds of explosive and killing four Protestant civilians, two policemen and an off-duty UDR man. “By this time”, Peter Taylor wrote in his book Loyalists, “many loyalists were beginning to see all Catholics and not just the IRA as the enemy.”

Protestant paramilitaries began to organise on an even larger scale than IRA. Two days before the IRA car bomb, William Craig, former Northern Ireland minister for Home Affairs, addressed a rally of up to 100,000 in Ormeau Park, Belfast. “We must build up a dossier”, he said, “of the men and women who are a menace to this country, because if and when the politicians fail us, it may be our job to liquidate the enemy”.

The two main Protestant militias, the newly-formed UDA and the more long-standing UVF, set about “liquidating” Catholics on a purely sectarian basis. Sectarian tit-for-tat murders multiplied. “In the first seven months of 1972” Taylor wrote, “the loyalist paramilitaries killed thirty-six Catholics while the IRA killed eighty-one members of the security forces and fifty-five civilians.”

Bloody Friday was an event organised by the Provisional wing of the IRA, according to Ed Moloney’s The Secret History of the IRA, as a ‘statement’ following an unsuccessful period of cease-fire. “The Belfast Brigade”, he wrote, “sent twenty of the new car bombs into the city and detonated them in just over an hour…in one of the worst days of violence yet.”

Moloney cites a former IRA activist of the time who later described why the carnage was so widespread. “We put it down to the Brits allowing bombs to go off, but the real reason was it was too much for the Brits to cope with, the bombs went off too close together, the town was too small, people were being shepherded from one bomb to another.”

Politically, Moloney suggests, Bloody Friday was an “unmitigated disaster” for the IRA, and it took years for the organisation to admit that it was its fault. Television screens in Britain showed (unusually) graphic detail of the effects of the bombings, with pieces of body parts being collected in black bin bags.

Body parts swept up into black bin bags

An account on the BBC website related that “Flying glass and debris from the blasts caused deep lacerations to people caught in the open, while many people lost arms and legs in the explosions and fireballs which followed caused horrific injuries”. One ambulance worker interviewed by the BBC said that a victim he encountered “was so badly injured that a specialist doctor had to look at them and decide whether they were male or female”.

Mic Craig writes: The TV footage showed emergency workers shovelling the remains of bodies off the street, into bags. I remember that my family were watching this on the 6 o’clock news at home and my dad got up from his seat and ran to the bathroom to throw up.

Years later, when the troubles ended, Archbishop Tutu presided over a sort of truth and reconciliation process which included interviews with some of the ‘combatants’ involved in the conflict here. One interview was with Billy McKee one of those who founded the ‘Provisionals’ on an explicitly ‘anti-communist’ policy, and who had been the IRA commander in Belfast on Bloody Friday. He was asked if he had any regrets about the deaths and injuries of innocent people on that day. He was unrepentant.

For the families who lost loved ones or for those who were seriously maimed on Bloody Friday, there has been no closure. No-one has been prosecuted. They have marked the fiftieth anniversary with calls for genuine remorse and for information about those who ordered the bombings and the reasons for them.

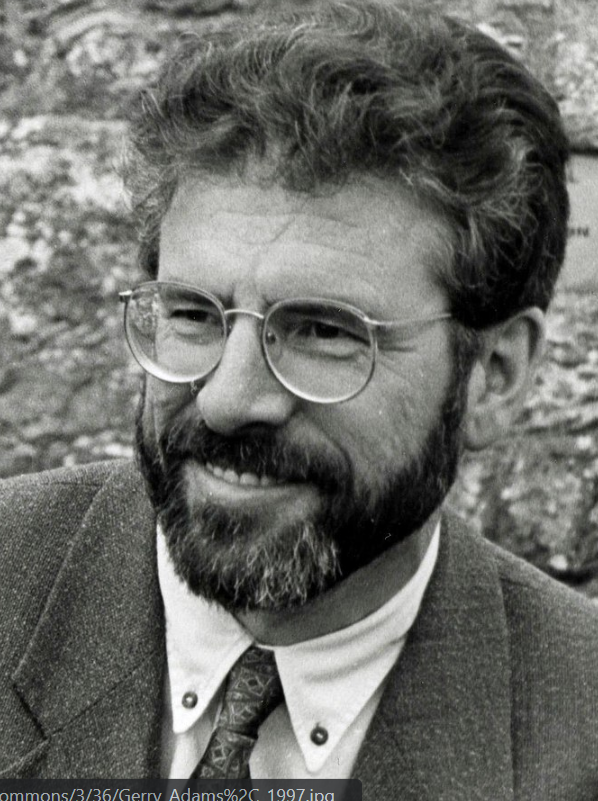

Writing in 1996, Gerry Adams, the former Sinn Féin president and a leading member of the Belfast IRA, said the IRA “made a mistake in putting out so many bombs” and he added that civilian fatalities were “a matter of deep regret”. What Adams will not say is that the entire so-called ‘military’ strategy of the IRA in Northern Ireland was an utter failure.

Unlike those on the left of the labour movement who might have illusions in the IRA and its ‘war’ – because of the British Army’s atrocities against Catholics in Derry and elsewhere – we should recognise that the IRA strategy added significantly to the deepening of sectarian divisions, and it is a divide that is still not bridged to this day. The IRA and its operations like Bloody Friday played a part in an what was at its most intense a bloody sectarian war.

Bloody Friday brought loyalist paramilitaries many recruits

According to Peter Taylor in Loyalists, “’Bloody Friday brought the loyalist paramilitaries as many, if not more, recruits as ‘Bloody Sunday’ did for the IRA”. Billy Hutchinson, a former UVF leader who has admitted taking part in sectarian murders, may not be a reliable witness to events at this time, but he supports this suggestion of Peter Taylor and his words ring true. In his memoir, My Life in Loyalism, he relates how Bloody Friday had a big impact on him as very young Protestant, at that time not even seventeen years old.

“Every person who joined a paramilitary organisation in Northern Ireland had a reason for why they decided to volunteer. Friday 21 July 1972 is a date that is often cited by former loyalist combatants as the day they crossed the Rubicon and decided either to join the UVF, the RHC (Red Hand Commandos) or the UDA.”

Research published in February in The Irish News showed that over 40 per cent of respondents in Northern Ireland believe that a blanket amnesty is the best way forward, but that still leaves nearly two thirds harbouring suspicions and fears about the motives of sectarian killings in the past and that is a legacy that cannot be overcome as long as the main political parties are themselves rooted in sectarianism.

The prime task for socialists today in Ireland is bridging that sectarian divide. Instead of the main political parties offering only a choice of one or the other sectarian camp, it is time for labour candidates to take the field and to offer policies, a programme and a future that is based on the needs of ordinary working-class people in all communities.

A recent poll showed that there is growing support for genuine non-sectarian Labour candidates in Northern Ireland. The recent LucidTalk poll (July) revealed that 32% of voters thought the Labour party should contest local seats. Almost a third of those polled would give the party a preference vote, albeit (at this stage) not first preference. The way forward has to be labour movement candidates fighting for socialist ideas.