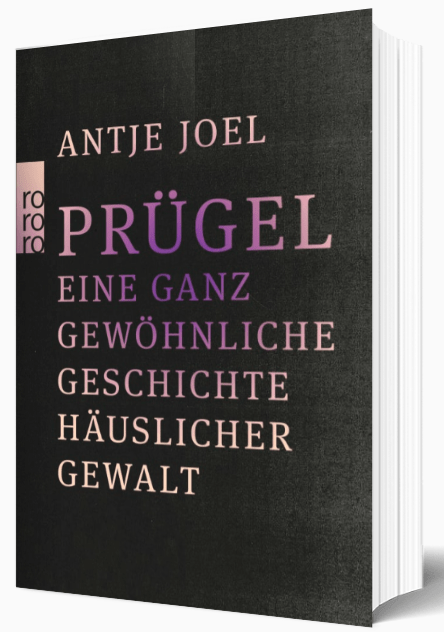

By Antje Joel

[Editorial note: Antje Joel, author of A Good Beating – An Everyday Story of Domestic Violence, describes the background to her book. It is a unique blend of personal story, global research, and exploration of how our socio-cultural and political structures enable and contribute to the violence.

Although it was published in German and the context is German society, what Antje writes is wholly relevant to the UK and other Western countries. The editors feel that this is an important article and as much as anything, we hope it stimulates a wider discussion on the political issues and the root social and economic causes of domestic violence]

…………………………….

Despite 50 years of international research, vigorous campaigning by women’s rights advocates and some policy changes, little progress has been made in the prevention of domestic violence. On the contrary, a growing number of women worldwide experience violence at the hands of an intimate partner.

In the book, Coercive control: the entrapment of women in personal life, ED Stark writes that “the revolution has stalled”. Grounded in my personal experience and academic research, this article explores possible reasons and concludes that “talking about it” alone does not suffice. It is also important how we talk about domestic violence and assault (DVA). And we must be prepared to listen to and hear its victims/survivors

“Why didn’t you just leave?”

It’s been 30 years since I fled down the stairs of a tenement house from a man, into the street, and on and on, haphazardly, with nowhere to go. The apartment I fled from was mine. The man who came after me, who – once again – made me fear for my life, was ‘mine’. We had been a couple, with interruptions, for five years at this point. We had been married for three years. We had two children. It was our last evening. The evening that I finally left.

“Why didn’t you just leave!” In what feels like 99 percent of the time, this question is still the first question I am being asked on the subject today. It took decades to find the right answer: “I did leave. I am here.” But of course, that’s not what matters in the eyes of too many others. What matters to them is that I did not leave for a while, or that I left “just to go back to him” a few times.

This not-leaving for a while, the going-back-again-and-again is what they think must define me. Back then anyway. And even today, after 30 years.

Anyone still bothering to ask why women do not or only hesitantly speak about the violence they have experienced or are still experiencing? That’s why!

“Why didn’t you just leave?” This and the many similar questions and remarks are excellent tools to silence women, to make them complicit in the violence they have suffered, to weaken them, keep them small. Even if they have long risen and finally, inwardly, found their strength. Is that “just” ignorance? Or is it a machinery of suppression? Is it the system?

For me, listening to survivors (finally!) is not equivalent to having them retell and live through the violence time and again, as we now see it daily in the press and on television. I believe that having them endlessly repeat their stories will do more damage. Firstly, I am acutely aware of the risk of re-victimization as a result. Secondly, with the repetition of ever new survivor-stories, I see the old myths repeated (and reinforced) over and over again.

The questions primarily focus on the personal and on always the same topics: Why didn’t the woman leave? What did she experience prior to the abuse, for example in her childhood, that later ‘led to her becoming a victim of partner abuse’? These investigations are often followed by a detailed description of the woman’s physical and psychological damage because of the abuse and tales of her ’emotional dependence’ on the perpetrator. It is a damage-centred discourse. The effects should be obvious, even to lay people.

We must focus on what happens after women speak out

The question is not: “How weak and damaged must a woman be, what must have gone wrong in her life that she ‘let him abuse her’?” The question must be: “Which forces must be at work when strong, self-confident women find themselves weakened, diminished, abused?” No man can accomplish this alone. There is a system behind each of these men. It supports them, even when they have killed their partners.

To prevent domestic violence and femicides, we must focus on what happens after women speak out (to friends, family). What happens after the abuse has become known to the authorities, what happens when women plan to leave the perpetrator or have left him. And we must focus on the impacts this has on women.

Why didn’t I just leave? I had good reason. The best. I hadn’t thought them up myself. They were offered to me, imposed upon me. Often by the same people who later declared that not going was my “biggest mistake”, who repeatedly voiced the thought, that somehow I was to blame, if not directly, then indirectly. Not much has changed since then.

A Berlin judge recently dismissed a woman’s claim for compensation despite being badly injured by her partner, on the grounds that she herself had caused the violence – by remaining in the relationship.

“It takes two to tango!” This is how my ex-husband used to argue that he was not responsible for his violence. “What did you do to provoke him?” asked friends I confided in at the time. In response to an article in a German nation-wide weekly, Die Zeit, on the subject of “Domestic violence in the times of Covid”, a reader wrote: “When hearing such stories, I always ask myself how the women contributed to their ‘victimization’! No man, no matter how nice, can and must endure constant nagging and being belittled be a woman!”

“These women often believe that the abuse is their own fault,” comment the usual ‘experts’, psychologists, psychotherapists, etc., who are reflexively asked for their opinion by the press and on TV, as if this perception was completely incomprehensible, as if believing to be at fault was just another of their many failures.

I often feared leaving more than staying

I didn’t leave because I often feared leaving more than staying. I thought, I would not be able to survive without him. The usual experts like to explain such feelings as “those women’s emotional dependency”, and yet another attribute of their defectiveness: “These women have often already experienced violence in their childhood – physical and mental violence. They weren’t brought up to be self-reliant and to feel valuable as human beings. Such people hope to find a relationship where everything will be fine. So, they will no longer have to deal with their painful childhood.” This expert comment was printed next to my – partly personal, partly factual – contribution to the topic in a German magazine. It was a women’s magazine dedicated to “changing the discourse.”

Grigsby and Hartman’s “barrier model” describes the victim of domestic violence surrounded by four concentric rings representing different barriers. The first barrier, from victim’s point of view, is the environment. Significantly, from the perspective of an outsider, it is the final barrier the victim must overcome (The Barriers Model: An integrated strategy for intervention with battered women, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 1997).

To be able to leave and escape their abuse, women need resources: money, a place of refuge, support from the police and courts, support from family, friends, social workers, therapists, etc. If these resources are lacking, or if they are unknown to the person in need of them or inaccessible to her, the message to her is clear: escape is impossible. Correspondingly, she experiences herself as worthless. This is another reason why making the provision and accessibility of above resources is crucial. Otherwise, any further intervention becomes pointless.

The next barrier is the woman’s family and society’s expectations at her as a wife/partner and mother. In our patriarchal society, women are still expected and made to carry the brunt of care for their relationships and their families. If the relationship fails, if the family falls apart, it is primarily the woman who is seen to have failed. How little these expectations and views have changed can be heard, read, and seen every day in politics, the press and TV. Most significantly in the already mentioned “empathetic” representations of victims in the media: humble, grateful, guilty, remorseful, forgiving, promising abstinence.

Guilt placed on them by the perpetrators and society

Women do not “blame” themselves. They accept the guilt placed upon them by the perpetrator and, compounding that burden, by society. That’s a difference. Like other domestic violence stereotypes and myths, it is a key obstacle for women to escape from the relationship and the perpetrator.

Women who are left with no choice but to remain in the relationship are left at the mercy of the abuser and made dependent on his promises and excuses. In the words of British criminologist Jane Monckton-Smith: “The perpetrator is the only one who can guarantee the woman’s safety.” (Domestic abuse, homicide and gender: Strategies for policy and practice)

In my second marriage, which was characterized primarily by verbal and psychological violence (physical violence – shaking, hitting, choking – he resorted to only after I had started to resist his psychological grip), I was the sole breadwinner in the family. I secured the livelihood for eight people, including six children. My husband “took care of the house.” Relatives and acquaintances were mainly laying at his feet for this extraordinariness. But there were other voices too. Those who ridiculed him calling him a “henpecked husband” and doubting his masculinity.

In fact, these voices did not differ. Both voices, those who praised him and those who ridiculed him, read from the same hymn sheet. They both sang the same disastrous gender role hymn. My husband knew how to make use of them both.

I sensed that early on in our relationship. But I only became aware of the scheme’s full extend in court, during the divorce proceedings. This man, who had been so devoted to his family, who consistently exhibited “female qualities” – caring, domestic, submissive – could not possibly be a violent offender. It was ridiculous to accuse such a man of violence. If he should have exercised it, then for good reason. “The client felt massively offended in his masculinity by his wife”, ruled the judge’s opinion.

Researchers identify having felt “insulted in their masculinity” as the dominant mitigating factor awarded to offenders (and killers) by judges. There is no female equivalent that could exonerate female offenders. Women who have killed their male partners are regularly punished more severely than men who have killed their female partners.

Women plead guilty more often than men

Even after having suffered years of violence at the hand of their partner, self-defence in female offenders is rarely recognized. At the same time, women plead guilty more often than men – if only in the hope of negotiating a slightly lesser sentence than is usually given to female partner-killers.

In contrast to my devoted soon-to-be ex-husband, the family judge recognized me as “self-centred”: “She always put her career above her family and her children.” My husband’s lawyers successfully claimed I had refused “to look after” my husband. My independence and my efforts to experience myself as valuable beyond my role as “wife and mother” had not protected me from violence in my marriage, and they did not protect me afterwards. On the contrary, they made me the target of “lawful” violence. From all sites, including from the state’s institutions.

During the divorce proceedings, the youth welfare office and the judge demanded that the children’s contact with their father must be maintained under all circumstances, and against their declared will, which a child psychologist had recognized as authentic. “Children who grow up without a father become criminals!” said the judge.

Apparently, he (also) was not aware that abuse of women and children by partners/fathers are overlapping crimes. Or maybe he ignored it: in 40 to 50 percent of cases of child abuse there is also abuse of the mother. Perpetrators are almost always fathers or stepfathers.

In the evenings, my husband often drove up and down in front of our house. He lay in wait for the children outside their school and had just recently volunteered as an assistant in their boy and girl scout group. The authorities and the court interpreted this as an expression of paternal longing. That the children only dared to leave the house when I accompanied them, they deemed a result of hysteria: mine.

The Monckton-Smith timeline to murder

The messages my husband left on my cell phone and the emails he sent me (“If you don’t call me on this number by 8 o’clock tonight, I’ll do what I deem right! ” – “I’m expecting you to meet me for talks in my new apartment. If you should be concerned about your safety: I don’t live alone.”) and which I submitted to the court were seen as an “understandable attempt of your husband to sort things out“.

I recently spoke with Jane Monckton-Smith about these messages. “Oh my god, that was your ‘last chance’“, she said. Monckton-Smith is a femicide researcher at the University of Gloucestershire, UK, and has developed an eight-step homicide timeline. In the “last chance” phase, the not-yet-killer gives the woman one last “opportunity” to reconcile with him, to return to him or to submit to his wishes in some other way.

This phase resembles level six on Monckton-Smith’s timeline and is characterized by a “shift in thinking/choice (to Kill)” based on the “perception (of the perpetrator) that he has no other way of dealing with his anger or feelings of injustice”. Level seven is the “detailed planning”, stage eight is murder.

The risk factors for intimate partner homicide have been known for decades. Most of these factors applied to my situation: the woman is planning to separate or has separated. Status and financial loss threatening the man because of the separation. Stalking of the woman by the man before and/or after the separation. The man is threatening, or has previously threatened, to commit suicide. The woman has children from a previous marriage. The woman fears for her life.

The latter, Monckton-Smith calls the “single most significant factor”. It is also the factor that police officers and lawyers are most willing and most likely to ignore.

In the United States, fatality reviews have been conducted since 1995 examining deaths and suicides after domestic violence. They examined the effect of interventions that took place before the killing. They are considering changes in prevention and intervention systems to avoid future killings. They develop recommendations for coordinated community prevention and intervention initiatives to reduce domestic violence.

Domestic Homicide Reviews (DHR) examine “circumstances in which the death of a person aged 16 and over was the result or apparent result of violence, abuse, or neglect by a person to whom (the person killed) is related was or with whom she was or had been in an intimate relationship, or who lived with her in the same household“. Since April 2011, DHRs have been mandatory for deaths that meet these criteria (Home Office, 2016).

Other means of risk-assessment

Since 2018, the British police has increasingly worked with Monckton-Smith’s Homicide timeline to assess a woman’s potential for danger and to avoid femicides as well as possible. Other means of risk assessment are the DASH and HIT questionnaires. Both are designed to address the “lack of understanding and training related to risk identification, assessment and risk management” that puts women at significant risk.

The developers also complain about the “failure to see the link between protecting the public and repeat offenses (in the area of domestic violence)”. And they point out that further training regarding the effective detection, assessment and management of IPF-risks is essential. “Without effective training, the same mistakes will be repeated over and over again” (DASH, 2009).

Germany – largely without research, education and uniform and comprehensive prevention – lives in the Pleistocene regarding the prevention of domestic violence and femicide, a fact that is ignored by politicians and the press alike. Katz described it as the main feature of dominant groups that their dominance is not questioned, let alone criticized, by themselves or by their subordinates (Macho paradox: why some men hurt women and how all men can help).

Boris Johnson, long before he became the British prime minister, declared “men who are unwilling or unable to control their wives” as ‘weak’. He further wrote: “Britain must reawaken women’s desire to be married.” After both my separations, the way German welfare officers, youth welfare officers, lawyers and family judges treated me, seemed like a concerted effort by state and society to “reawaken” this desire in me. At least, I should recognize my leaving as a mistake.

60 per cent of fathers never pay a single cent

Effective means and ways to make women sorry for leaving or stop them from leaving in the first place remain in place today: For example, 60 percent of separated German fathers never pay a single cent maintenance for their children. Only a quarter of fathers pay the full rate. The margin in between pays a little here and a little there. In the face of this, state authorities declare themselves powerless. Worse still, in custody and visitation battles, these fathers’ unwillingness to pay maintenance is deemed irrelevant for their ability to love and care for their children.

Both men I was married to never paid a single cent of maintenance. Despite this, I was urged by youth welfare officers and the family judge to “only speak positively to the children about their father”. When I resisted their coercion, and violence, I was threatened with hefty fines and, in case I should fail to pay, jail. The children were threatened they would be collected by police or a bailiff and taken to see their father by force.

Meanwhile, I was forced to sell the family home at great loss. Because the man who paid neither alimony nor his share in mortgage was irrevocably a co-owner. This all went on, relentlessly, for five years. Until my children and me finally fled, 2,000 kilometres abroad. Thanks to legal aid, my ex-husband was able to terrorize us further, for another six months. Then there was silence. Predominantly, because he had died. And all this is only a very small part of all that transpired. Long after I had left him.

The strength it takes to keep going alone renders the long-distance diagnoses of psychologists on talk shows and magazines absurd. And yet, whenever I tell the story of my two marriages, someone inevitably will ask: “Why didn’t you just leave?” I hear politicians and people say: “The women have to confide in someone, they have to speak openly about the violence!” How? When as soon as they dare to do so they are branded ‘Dependent!’. ‘Failed!’. ‘Defective!’ When, despite international research and knowledge, they are still being blamed (sometimes openly, sometimes under the banner of empathy and empowerment) for the violence they have experienced. In Germany, this is still part of everyday life. It is part of the collective notion of “reason”. Of objectivity. And of dignified reserve.

Some women who faced abuse now work in shelters

Informal and formal helpers and activists, too, regularly contribute to the stigmatization and exclusion of victims/survivors. I know women who have experienced abuse and now work in women’s shelters. They are forbidden to reveal themselves as victims/survivors of partner abuse, especially in front of their clients. I know female managers of women’s shelters who would “never hire a woman who has experienced abuse”.

Their reason being that such women would “just try to resolve through her clients what she couldn’t resolve for herself”. I know policewomen who have been victims of partner abuse, and who are forbidden to reveal this when dealing with a victim/survivor. “This reminds me of the perpetrators”, one of them said. “Their first demand is that we remain silent.”

Also replicating the perpetrators attitudes and behaviour are the politicians, helpers, and activists who “speak for the victims”. Who claim to “give these women a voice”, through their own speeches, campaigns, etc. This, too, is a form of oppression and exploitation.

Women do not need people who speak for them (yet again). They need the space and security that allows them to raise their voices. They need to be heard. As equal partners in a discourse that is – predominantly – about them.

Antje Joel has an MA from the University of Worcester, in Understanding Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. In October, she begins PhD research under the supervision of Jane Monckton-Smith. The book, which is unfortunately still available only in German, can be sourced here. Her dissertation study, Promoting Shame and Stigma – Media representations of victims of DVA explores how the public depiction of DVA and its victims may contribute to violence.

In September, she will be speaking at the 5th Annual Ethnographies of Crime Symposium at King’s College, University of Cambridge.

She can be contacted for comment here:antjejoel@hotmail.com