By John Pickard

Most socialists are ‘green’ socialists, in that they have a clear understanding of the dangers posed to society, and even to humanity, from global warming. You might have thought that we were all hardened to the mountain of evidence supporting the idea of climate change. Nevertheless, even for us, there are still sometimes scientific articles and reviews that are shocking and which make grim reading.

One such article was the ‘long read’ in the Financial Times on August 23, entitled Methane hunters: what explains the surge in the potent greenhouse gas? As the title implies, the focus was entirely on methane gas and its contribution to global warming.

It has long been known that methane (CH4) is 80 times more potent a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide (CO2), although methane does not stay permanently in the atmosphere, being oxidised in time to carbon dioxide. But the scale of increased emissions of methane are something that is not fully understood.

The historical increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide are almost all due to the burning of fossil fuels, coal, oil and gas which took tens of millions of years to be created but only two centuries to burn. Most methane, on the other hand, comes from ‘natural’ sources, although leakage and venting from natural gas extraction processes is a factor. Although the creation of methane might be considered as ‘natural’, the result of microbial metabolism, this might also include gas from landfill sites, rice paddies and tens of billions of domestic animals reared for meat, so in that sense, it is not ‘natural’.

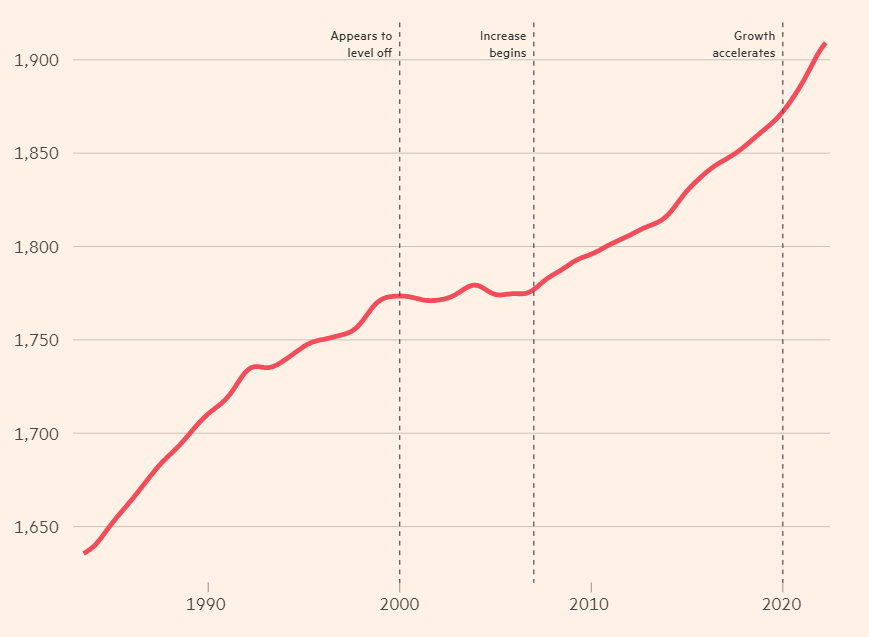

The Financial Times article in question looked at research currently under way to determine the reason for the large jump in atmospheric methane and its possible causes. The scale of the jump can be seen on the graph. Atmospheric methane is currently at its highest-ever level recorded by modern instruments. The aim of the research is to see why.

A ’surge’ in atmospheric methane

A laboratory in Colorado, run by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, analyses samples of air taken regularly by fifty monitoring stations around the world. The laboratory analyses the air for all of its gaseous content, including tiny amounts of methane, measured in parts per billion.

“About 15 years ago,” the FT article notes, “its researchers observed an uptick in atmospheric methane…In the past few years, however, that uptick has accelerated into a surge.” The highest-ever figure that had been recorded using modern instruments, for atmospheric methane, was in 2020 but that record was broken again the year after. “It is shocking,” said one of the researchers in the Colorado laboratory. “A lot of research, a lot of scientists, are trying to explain it.”

Previously, it had been assumed that the increase has been due to human activity like gas extraction (and leaks), landfills and large scale agribusiness. Now, however, there is a different theory which is gaining ground – that the increase is itself a product of climate change, and therefore not something that can be easily countered by a change in human activity.

As the FT says, “the implications for global warming are immense” and it suggests that of the 1.1oC rise in average world temperatures since the Industrial Revolution, as much as one third may be attributed to methane.

‘Fossil’ methane and ‘modern’ organic methane

it is possible to distinguish between ‘modern’ methane – that is methane being produced today by natural processes – and fossil methane (in natural gas and oil) by measurement of the isotopes of carbon in each. Ancient methane, laid down in the Earth tens of millions of years ago, has a higher proportion of Carbon-13 isotope than methane produced in recent times from natural processes.

The salient point is this. Before 2007 the proportion of methane in the atmosphere was disproportionately due to fossil fuel burning. But after 2007, the ratio between the two has tipped in the other direction: ‘modern’ methane now exceeds ‘fossil’ methane in the atmosphere. The implication is that from around fifteen years ago, there has been an increase in natural methane production that is not directly related to human activity.

If the increase in atmospheric methane is no longer due to the release of fossil fuel, natural gas, then, as one of the scientists told the Financial Times, “it means something significant has happened”. If it is not from fossil fuel emissions, then what is it?

One serious suggestion gaining traction, is the possibility of a big increase in methane from melting permafrost in Siberia and Northern Canada and an increase in wetlands and shallow lakes in the tropics.

Permafrost, such as the permanently frozen tundra in Siberia, holds billions of tonnes of trapped methane. Siberian alone has billions of tonnes of carbon locked in. We have also seen in the last few years record high temperatures in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. There were even forest fires in Siberia quite recently.

If higher temperatures are sustained in Northern Europe and Canada, it will inevitably mean that what was ‘permanently frozen’ becomes thawed, releasing tonnes of methane. Not only will trapped methane be released, but the natural process of decomposition of organic matter produces more methane. As the permafrost melts, it forms new lakes (known as ‘thermokarsks’) and wetlands, where natural decomposition processes are again accelerated – producing more methane again.

Increases in wetland emissions by bacterial decomposition

Likewise, it is possible that changes in weather patterns in East Africa and elsewhere have produced more shallow lakes and wetlands than there had been previously and, in these areas, once again, natural processes would tend to increase production of ‘new’ methane from decomposition. The wetter the wetlands, the greater the microbial methane emissions. It is worth noting that the increases in wetland methane emissions has only been known about for two or three years, so the science around it is new.

Those scientists trying to work out the answer to this conundrum are effectively racing against time to find answers. What everyone fears is a positive feedback loop, whereby a warming planet increases the production of methane, further warming the planet in a self-perpetuating cycle – a scenario described by one scientist as a “methane bomb.”

“If you think of fossil fuel emissions as putting the world on a slow boil, methane is a blow torch that is cooking us today,” said Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, and a leading advocate of stricter policies to reduce methane emissions. (FT)

There is not a consensus among all scientists as to the cause of the surge in atmospheric methane. “Wetlands and cattle appear to be the biggest culprits”, according to Euan Nisbet, professor of earth sciences at Royal Holloway, University of London. But, “the biological sources are increasing faster,” he says. “The most intense growth seems to be coming from the tropics.” Nisbet also points to a global increase in landfill sites and cattle-raising for meat.

The Financial Times article cites an upcoming science paper, which concludes that “85 per cent of the increase in atmospheric methane since 2007 is due to microbial sources. And about half of that is from the tropics. Using satellite data, Palmer has zeroed in on east Africa as a source of increased emissions, such as the Sudd wetland in South Sudan”.

Katey Walter Anthony, Professor of ecology and biogeochemistry at the University of Alaska, told the Financial Times, “Permafrost itself contains around 1,500bn tonnes of carbon…as permafrost thaws, that carbon can be turned into methane by micro-organisms known as methanogens”. Having flown all over Alaska to measure the methane emission of lakes, she has been surprised by the results. “In the last five to six years, I have just seen incredible change,” she says. “It seems like we crossed a threshold and we are seeing crazy things happening.”

Methane could become the dominant greenhouse gas

“In interior Alaska we’ve seen a nearly 40 per cent increase in lake area since the 1980s, of new thermokarst lakes forming,” says Anthony. “Those lakes emit methane at least 10 times higher than a normal lake, they are hotspots.”

The upshot of the global research seems to be that science has underestimated the significance of methane in current and particularly in future climate change. Indeed, methane could become the dominant source of atmospheric warming by the middle of this century, if current warming trends continue – which looks likely.

At the COP26 conference in Glasgow last year, more than 100 countries signed up to the Global Methane Pledge, aiming to cut methane emissions collectively by 30 per cent this decade. It is ironic that this target, if it was achieved, could have a more immediate effect on global temperatures – as measured in a human lifetime – than CO2 reduction. And the quickest way to reduce atmospheric methane is to cut accidental emission of fossil methane – which means reducing natural gas extraction and venting. Unfortunately, the biggest global emitters of methane, China and Russia, did not sign up to the pledge at COP26.

Articles like this in the Financial Times – and there will be similar contributions in many science journals – make grim reading. The two obstacles to human progress are, on the one hand, private ownership of the means of productions, distribution, and exchange (capitalism) and, on the other, the nation state. One chases short-term financial gain for a tiny handful of the population at the expense of all of humanity. The other is expressed in national rivalries, competition, and wars between states, as governments represent the interests of their own narrow cliques against others.

Capitalism and the nation state are no longer just obstacles to human development. They are obstacles to the continuation of human civilisation. Where we have seen an increase in average global temperatures more or less gradually over the last century, there is no guaranteed that a slow, steady rate of change will operate in the future. Nature, in all its processes, changes dialectically, with periods of gradual quantitative shift interspersed with dramatic, sudden and qualitative changes.

We are in a race against time to change society. It is no good despairing or shrugging one’s shoulders at the sombre scenarios outlined by scientists. On the contrary, the more we read the science, the more we should see the urgency of the struggle to change society. We owe it to our children and grandchildren.