By Michael Roberts

“If there was no intervention today, gilt yields could have gone up to 7-8 per cent from 4.5 per cent this morning and in that situation around 90 per cent of UK pension funds would have run out of collateral… They would have been wiped out.” So says a UK bond trader yesterday.

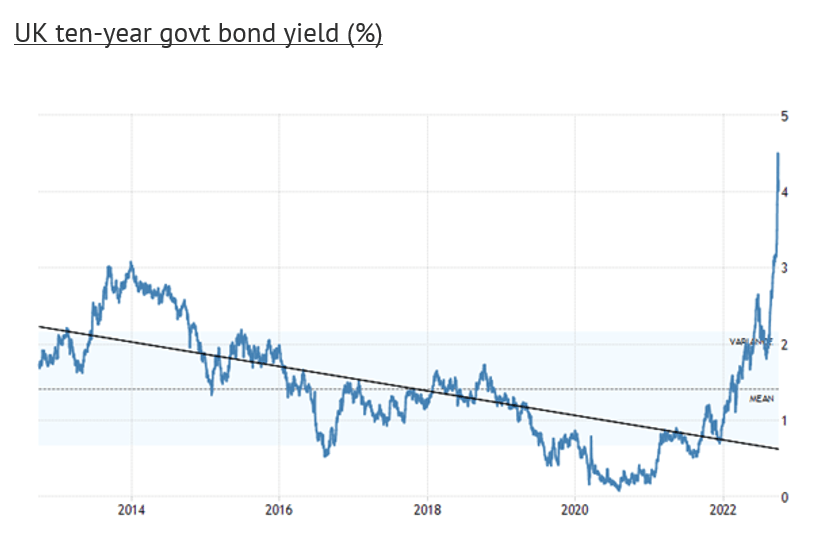

A liquidity crisis erupted in British bond markets after the announcement by the new right-wing Conservative government that it would spend up to £60bn to maintain an energy price cap for householders for up to two years, subsidise business energy costs AND also cut corporate and income taxes. The total hit from this largesse (mainly to the rich) to the UK public debt level over the next few years has been estimated at over £400bn or nearly 20% of GDP. With UK public debt already at 100% of GDP, that sounded the death knell for the UK bond prices. Yields (interest rate) surged.

Alongside this, the Bank of England plans to hike interest rates yet further over the next year to ‘control’ inflation. So the cost of borrowing and servicing debt is rocketing. Suddenly, investors holding government bonds were facing serious losses, particularly pension funds that tend to invest on long-term bonds using short-term interest rates to borrow – short-term interest rates up; long-term bond prices down. That’s a mismatch on asset values and a credit liquidity squeeze was on.

Buying bonds to use as collateral…to buy more bonds

In the case of the UK, apparently pension funds and others had been employing yet another piece of financial jiggery-pokery called “liability-driven investment” schemes. This was the practice of buying bonds that are then used as collateral for loans to purchase more bonds – as much as £1.5trn over the last decade since the global financial crash. If the value of the bonds used for collateral drop like a stone, as they have just done, then the ability to borrow vanishes. So the BoE has been forced to loan £65bn to such bond holders to bail them out of their Ponzi scheme.

And it was not just in the UK with its crazy government. Even in the US, with supposedly a ‘sensible’ administration that is not cutting taxes or funding price caps, the credit squeeze is also there. The $24tn US treasury market has been hit with its most severe bout of turbulence since the coronavirus crisis, underscoring how big swings in international bonds and currencies and jitters over US rate rises have spooked investors.

“Right now, it is all about market volatility,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, a strategist at TD Securities. “You have investors staying away because of the volatility — and investors staying away increases volatility. It is a volatility vortex.”

The US 10-year treasury yield, a key benchmark for global borrowing costs, has surged to more than 4 per cent from 3.2 per cent at the end of August, leaving it set for the biggest monthly rise since 2003. It is on track for its sharpest ever annual rise. The two-year yield, more sensitive to fluctuations in US monetary policy, has leapt 3.55 percentage points this year, which would also mark an historic increase.

Tightening liquidity (credit) has hit all those wild speculative assets hard. Take so-called non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Trading volumes for the ridiculous NFTs have tumbled 97% since January, and the blockchain-bound digital art and collectibles market went from $17 billion to just $466 million in September, according to Bloomberg. Similarly, the fall in the Bitcoin price has wiped out nearly all the gains from cryptocurrencies of the last few years.

Two blades of the scissors

As I have argued in previous posts, there are two blades of the scissors that are closing to deliver a slump: falling profitability and rising interest rates; or falling earnings and tightening liquidity, if you like.

Take the first blade. Marx explained the role of credit in capitalist production very clearly in Capital. Credit is essential for capitalist investment and production: “the credit system accelerates the material development of the productive forces and the establishment of the world-market. It is the historical mission of the capitalist system of production to raise these material foundations of the new mode of production to a certain degree of perfection.”

But this beneficial role for capital has a dark side. “The credit system appears as the main lever of over-production and over-speculation in commerce solely because the reproduction process, which is elastic by nature, is here forced to its extreme limits, …. the self-expansion of capital based on the contradictory nature of capitalist production permits an actual free development only up to a certain point, so that in fact it constitutes an immanent fetter and barrier to production, which are continually broken through by the credit system.”

So credit helps capitalist production to continue even when profitability is falling but only “up to a certain point”, after which “credit accelerates the violent eruptions of this contradiction — crises — and thereby the elements of disintegration of the old mode of production.” In other words, the level of credit now becomes debt that acts as a burden on further expansion and even triggers crises.

If the gap between inflated financial prices and profits in the rest of the economy is large enough, a financial collapse can precipitate a full-blown recession. All of a sudden, credit dries up. When credit is needed the most, financial institutions are too frightened to lend it. As Rosa Luxemburg once argued, “after having (as a factor of production) provoked overproduction, credit (as a factor of exchange) destroys, during the crisis, the very productive forces it created.”

But as Guglielmo Carchedi puts it: “the basic point is that financial crises are caused by the shrinking productive base of the economy. A point is reached at which there has to be a sudden and massive deflation in the financial and speculative areas. Even though it looks as if the crisis has been generated in these sectors, the ultimate cause resides in the productive sphere and the attendant falling rate of profit in this sphere”. (Behind the Crisis).

Cumulative global profits are still depressed

And that brings us to the other blade in the scissors of slump: profits. I have discussed what is happening with profits in a recent post. Corporate profit margins, having reached record highs, are now sliding down as the costs of production rose from the end of the COVID slump and revenue growth slows.

In a report, JP Morgan economists concluded, “relative to its pre-pandemic trend, cumulative global profits since the pandemic are still over 20% depressed.” And now profits growth is disappearing. JP Morgan forecasts that “Combined with rising interest rates, profit margins will fall, dampening overall earnings.”

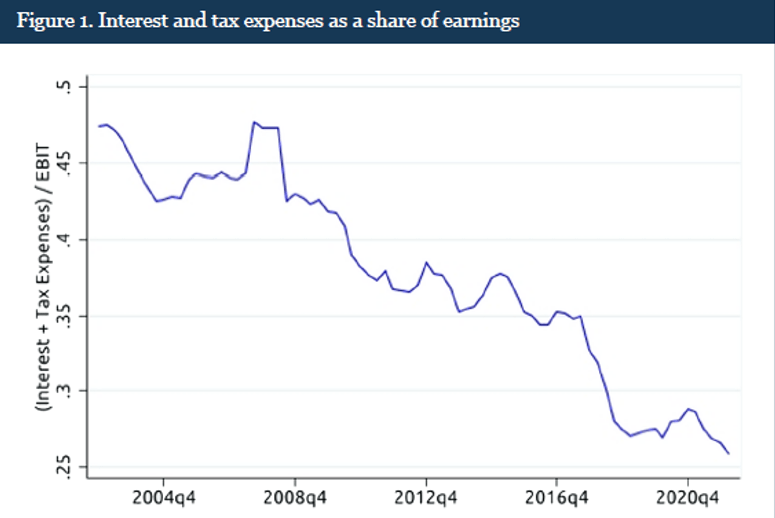

Even the Federal Reserve has noted this. In a recent paper, a Fed economist noted that “over the past two decades, the corporate profits of stock market listed firms have been substantially boosted by declining interest rate expenses and lower corporate tax rates.” These factors were responsible for a full one-third of all profit growth for S&P 500 nonfinancial firms over the prior two-decade period.

The significant decline in corporate interest rates allowed interest expenses to decline as a share of earnings, even as corporate debt rose.

This was a feature of 21st century capitalism: falling interest rates and plentiful liquidity, even in a period where profitability was not rising. Indeed, the response to falling profitability in the major economies was not to go for liquidation of the weak and unprofitable to clear the decks, but instead for the monetary authorities to save the banking system and prop up ‘zombie’ companies with zero- interest rate policies and ‘quantitative easing’.

But all this has done is to expand the credit-debt mountain to unprecedented highs without restoring profitability in the productive sectors. The bulk of the rise in earnings has been from speculation in the financial sector, property and in a few technology areas. The rest of the productive base of capitalist economies has been struggling – thus we have low investment growth, low productivity growth and ever larger credit liabilities that, as profits now begin to fall, are coming back to bite capital.

Quantitative easing and quantitative tightening

Rising inflation has led to rising interest rates as central banks switch from quantitative easing (QE) to quantitative tightening (QT) to try and control inflation. However, that is just exacerbating the slowdown in growth into outright recession – and generating a credit squeeze that threatens to hit not only financial assets but also corporations globally. So it’s back to QE!

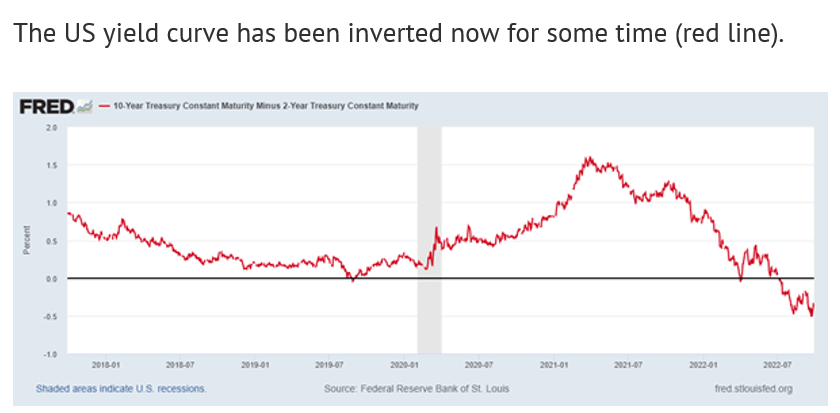

In previous posts, I have noted that an inverted bond yield curve is a pretty accurate indicator of a coming slump. An inverted yield curve is when the interest rate on, say, ten-year debt is lower than on 3m or 2yr debt. That only happens when investors are so worried about possible recession that they tend to buy government bonds as a safe haven, driving down their yield, while central banks are hiking short-term rates to levels that threaten to bring down the financial house of cards.

One analysis reckons that since 1990, a 1 per cent increase in the Fed Funds rate (the central bank rate) flattens the 2-10 yield curve by 35 basis points on average. So, if the Fed Funds rate hits 4.75 per cent as forecast by the market that could flatten the curve by 1.58 per cent, leading to a curve that is inverted by as much as 1.28 per cent (the 2-10curve started this year at 0.3 per cent) by the end of the year.

Moreover, this credit squeeze is being exported by a strong dollar to the rest of the world’s economies, particularly those with large dollar-denominated debt. The US dollar is super strong against other currencies as it is seen as a ‘safe-haven’ for investors to hold their cash and assets as inflation spirals and the world slips into recession. But a strong dollar and rising interest rates are pushing the world economy into slump. “These recessionary forces emanating from the US and the rising dollar come on top of those created by the big real shocks. In Europe, above all, there is the way in which higher energy prices are simultaneously raising inflation and weakening real demand.” Martin Wolf, FT.

Inverted yield curve confirmed

And the recessionary forces are getting stronger to the point that many economies are probably already in a slump. The latest forecasts by the World Bank and by the OECD, as well as the IMF, portend a slump, confirming the indications of the inverted yield curve. In its latest economic forecast, the OECD reckons the world economy is slipping into recession driven by high energy prices, rising interest rates and China’s slowdown. The OECD now forecasts just 2.2% global growth next year and as 4% is needed to keep pace with rising global population, that will mean a fall in per capita growth.

“The world economy is paying a high price for Russia’s unprovoked, unjustifiable and illegal war of aggression against Ukraine. With the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic still lingering, the war is dragging down growth and putting additional upward pressure on prices, above all for food and energy. Global GDP stagnated in the second quarter of 2022 and output declined in the G20 economies. High inflation is persisting for longer than expected. In many economies, inflation in the first half of 2022 was at its highest since the 1980s. With recent indicators taking a turn for the worse, the global economic outlook has darkened.”

The OECD wants to blame the impending recession on the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Putin, but the world economy was already heading into a slump just before the COVID pandemic broke and the recovery after the COVID slump was already petering out in 2021 before the Russian invasion.

The World Bank is more accurate: “To cut global inflation to a rate consistent with their targets, central banks may need to raise interest rates by an additional 2 percentage points, according to the report’s model. If this were accompanied by financial-market stress (which has now started – MR), global GDP growth would slow to 0.5 percent in 2023—a 0.4 percent contraction in per–capita terms that would meet the technical definition of a global recession.”

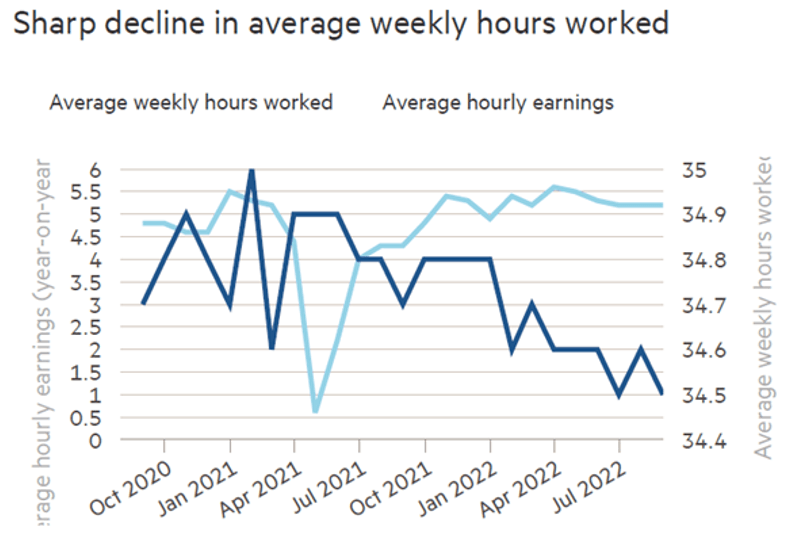

Full-time jobs in US are falling

One of the features of the 21st century in the major economies has been low unemployment, at least in the official figures. But much of this employment has been in low-paid services sectors, part-time or temporary. Now even here, there are signs of cracks. In the US, full-time jobs are falling, to be replaced by part-time employment. And in another sign of a weakening labour market, weekly working hours are down over the last six months to the lowest reading since the COVID slump in April 2020.

The other feature of the last decade and post-pandemic period in both the US, Europe and the UK has been the huge rise in property prices. That too is now showing signs of fading. This month home prices in the US fell outright for the first time since 2012. Mortgage rates have doubled, making it increasingly impossible for many to buy homes.

So falling profits; rising interest rates; slowing economies and a credit crisis. “What can be done?”, asks FT columnist Martin Wolf –“Not that much.”, he replies to himself. The impending world slump cannot be avoided. “What is known is that the central banks’ ability to support the markets and economy are for a while gone…Even previously credible G7 governments, such as the UK’s, are learning this truth. The financial tide is going out: only now do we notice who has been swimming naked.”

Or are they already drowning?

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.