By John Pickard

In two weeks’ time, COP27 will open in Sharm El Sheik, Egypt. It is a year since COP26 was held in Glasgow and few, if any, of the pledges made at that conference have been fulfilled. As Greta Thunberg said at a rally in Glasgow at the time, it will be more “blah, blah, blah”.

The Egyptian government, a vicious military regime that suppresses any signs of opposition or dissent, with tens of thousands of political opponents in jail, will not be using COP27 in an earnest attempt to make a difference to climate change. Like polishing a turd, it will use COP27 only as an attempt to put a gloss on its dubious international reputation.

There is little likelihood that yet another international conference will make the necessary impact on world governments or the giant corporations, both privately and state-owned, that determine global energy policy. All of them will be represented by scores of agents and lobbyists, making sure there are no solid commitments beyond fine-sounding phrases.

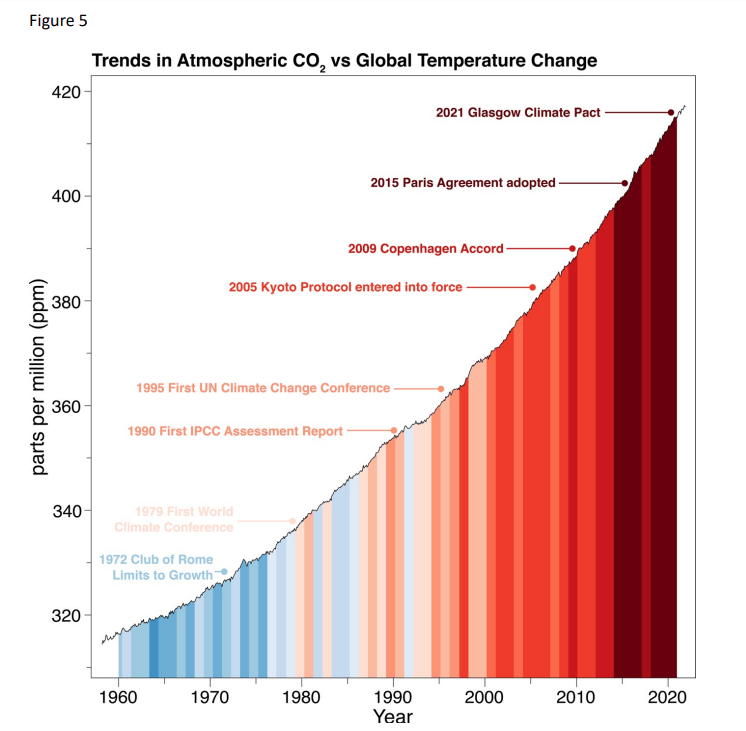

A paper produced this week by academics at UCL was entitled, A short history of the successes and failures of the international climate change negotiations and it has to be said that the ‘successes’ have a very short history indeed, whereas the failures could fill a book. The authors of the paper, Mark Maslin and John Lang, write, “The last 30 years have been a period of intense and continuous international negotiation to deal with climate change. During the same 30 years, humanity has doubled the amount of anthropogenic carbon dioxide in the atmosphere…”

“very limited progress has been made…”

Although the Paris Agreement, signed in 2015, committed scores of states to strenuous efforts to keep climate change at or below 1.5oC, the results have poor to non-existent. Referring to pledges made at last year’s conference in Glasgow, the authors conclude, “…currently these pledges, if fulfilled, will only limit global average temperature to 2.4˚C to 2.8˚C”.

In preparation for the new COP conference, scientists from the United Nations Environment Programme have published their own estimates, in a document tellingly entitled Emissions Gap Report. Since COP26, the Executive Summary notes: “there has been very limited progress in reducing the immense emissions gap for 2030, the gap between the emissions reductions promised and the emissions reductions needed…”

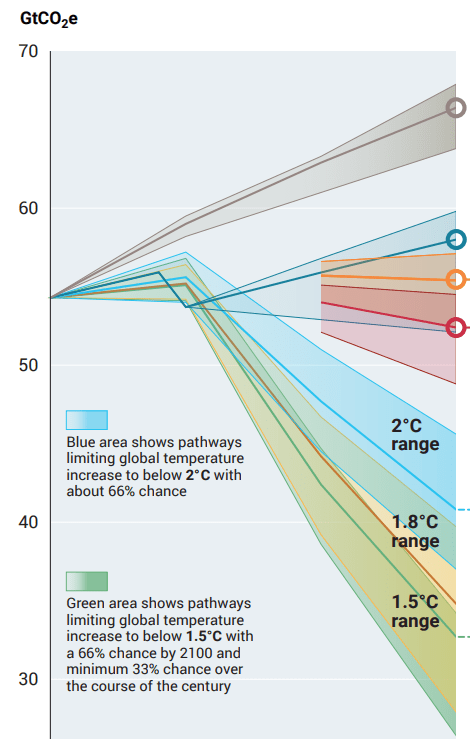

Rather than decreasing emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG), the report says, “global GHG emissions for 2021, excluding LULUCF [land use] are preliminarily estimated at 52.8 GtCO2e [gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent], a slight increase compared to 2019, suggesting that total global GHG emissions in 2021 will be similar to or even break the record 2019 levels”

“…Emissions under current policies are projected to reach 58 GtCO2e in 2030. This is 3 GtCO2e higher than the estimate of last year’s report”. Referring to the agreement to limit temperature rise to 1.5oC, as agreed in Paris, the report concludes, there is “no credible pathway 1.5oC in place”

The grim conclusions of this report are that “without additional action, current policies lead to global warming of 2.8°C over this century. Implementation of unconditional and conditional NDC scenarios reduce this to 2.6°C and 2.4°C respectively”.

Profit and geo-political prestige

“We are headed for a global catastrophe,” UN secretary-general, António Guterres, complains, “The emissions gap is a by-product of a commitments gap…Global and national climate commitments are falling pitifully short”. He is right, of course, but those who really control world energy production and use are not the scientists or even government representatives at the COP conferences. Their pious wishes are completely at odds with the hard-headed calculations of governments and big energy corporations who base their investment decisions entirely on their profits and/or geo-political prestige.

Referring to the latest UN reports, Tory MP Alok Sharma, who was the chair at COP 26, said, “It is critical that we do everything within our means to keep 1.5oC in reach, as we promised in the Glasgow Climate Pact. These reports show that although we have made some progress – and every fraction of a degree counts – much more is needed urgently. We need the major emitters to step up and increase ambition ahead of COP27.”

He says this on the one hand, yet he happily supports a government that has just issued a hundred new exploration licences for oil and gas in the waters around the UK. Sharma’s party leader and Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, is so little animated by the issue of climate change that he cannot even be bothered to go to COP27. Sharma’s bleating about “doing everything within our means” is typical of the doublethink and hypocrisy of politicians on climate change.

Nearly all of the countries represented at the Glasgow conference agreed to revisit and improve their commitments towards becoming carbon neutral, but in fact few have done so. Some of the biggest carbon dioxide and methane emitters, like the US and China, have made some investments in renewables, but their climate targets are still seriously lagging. Overall, the updated targets announced by governments for 2022 would reduce emission by less than one percent by 2030, an insignificant figure alongside the 45 per cent signed up to in the Paris agreement.

Some of the smallest carbon emitters suffer most from warming

Another UN body, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNCCC) also produced a report this week along the same lines. Their press release on October 26 says, “the combined climate pledges of 193 Parties under the Paris Agreement could put the world on track for around 2.5 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century.”

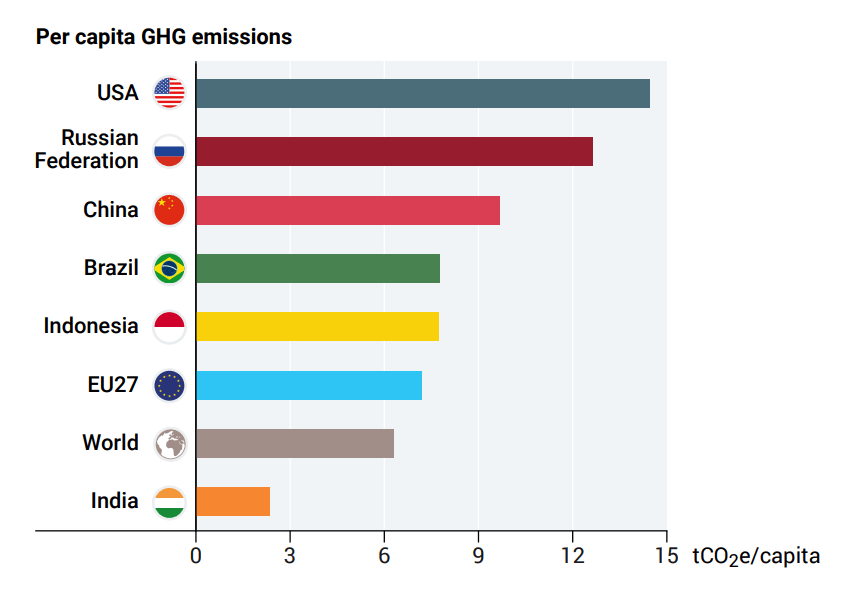

The greatest irony of all is that the smallest carbon emitters are on course to suffer the most from climate change. The richest twenty countries on the planet, represented by the G20 members, emit 75 per cent of global greenhouse gases. While the world average per capita GHG emissions is only 6.3 tons of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) in 2020, the figure for the USA is above 14 tCO2e.

Pakistan, for example, responsible for around 1% of global carbon emissions, has suffered devastating floods, affecting a third of its total area. Extreme weather events will become increasingly likely as the century wears on and average global temperatures creep upwards.

The latest findings, an article in the Financial Times notes, citing the executive director of the UN environment programme, demonstrates “in cold scientific terms what nature has been telling us, all year, through deadly floods, storms and raging fires: we have to stop filling our atmosphere with greenhouse gases, and stop doing it fast”.

With the global economy recovering after the Covid pandemic recession, “energy-related carbon emissions rebounded after the pandemic to the highest level in history in 2021 at 36.6bn tonnes, and the annual rise in methane concentrations in the atmosphere was the largest since records began.”

Life-changing weather anomalies

Temperatures have already risen at least 1.1C since the dawn of the industrial era. In a measurable period of time there may be dramatic and life-changing weather anomalies and climate disturbances that affect millions of people. It is absurd to imagine that global warming will always follow a gradual and smooth path upwards. As with everything else in nature, it will move dialectically: there will be periods of gradual quantitative change, interspersed with sudden and dramatic qualitative changes.

Dramatic ‘anomalous’ weather events, increased deaths from heat exhaustion, wildfires, floods, crop failures, populations shifts and all the consequent economic political upheaval that come from these things are on the cards for the middle of this century – and that is not such a long way off.

The UN Report concluded that “wide-ranging, large-scale, rapid and systemic transformation is now essential to achieve the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement”. That may also be true, but “systemic transformation” has to mean a complete and revolutionary change from one social and economic system to another, or it means nothing.

Capitalism and its giant corporations, with the governments that are in their pay, can never be relied upon to save the planet. They have to expropriated and managed democratically, so that planning, investment and economic strategy can be based around the needs of the planet and its population, and not on profit.

Social movements around climate change will increase

The two UCL academics mentioned above noted the growing movements there are on climate change, particularly among young people, and their shift towards “radical direct action”.

“Borne out of the frustration that many climate campaigners feel from the lack of action by Government and many corporations,” they write, “direct actions have included: Insulate Britain protestors gluing themselves to motorways: Just Stop Oil protestors gluing themselves to famous painting; protestors letting down the tyres of large SUVs in cities; and the sabotaging of oil pipelines and refineries. Many activists now see direct action and violence as the only way that government authorities will take note and act – in the US this has been defined as eco-terrorism.”

Apart from ‘greenwashing’ and a few cosmetic changes, environmental movements have so far not been able to produce notable shifts in national or international energy policies. It is no surprise that many young people are “frustrated” and angry. Indeed, it is inevitable that such movements will increase, because so little in the way of real change is taking place.

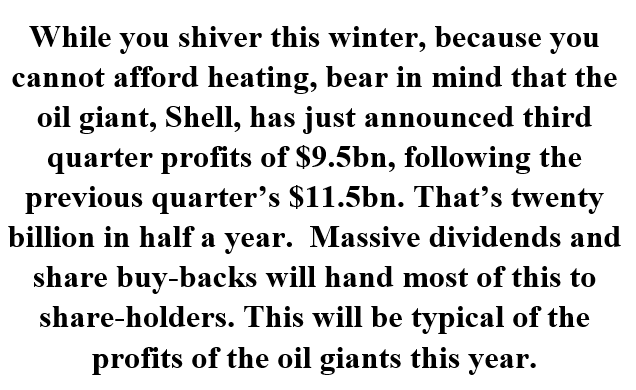

The key players are not those companies that use energy – and the wealthiest of them can take some steps towards carbon neutrality – but those who extract and sell energy oil and gas. These companies will not change as long as they are in private hands, or in the hands of dictatorial governments.

We may not support all and every one of the tactics used by climate protesters – it is hard to see how vandalising a Van Gogh, for example, can raise awareness – but we should have sympathy for their aspirations and motives. And few socialists would complain if they made the big energy companies and a few government ministers their prime targets for disruption.

[Top picture: part of The Guardian front page today]