By John Pickard

There is an old saying that “there is one law for the rich, and another law for the poor”. It is completely true, of course, and we got yet another example of it last week, when one of the world’s biggest mining, commodity and oil conglomerates was fined for criminal behaviour, but not a single director was even in the dock.

Glencore was ordered to pay a massive £276mn in fines and costs by a court in London for having run a network of bribery and corruption across Africa, through one of its subsidiary companies. According to the Financial Times, (November 3) the judge in the case said that the company was guilty of “corporate corruption on a widespread scale, deploying very substantial amounts of money in bribes”.

The subsidiary, Glencore Energy UK, had already pleaded guilty to seven counts of bribery in several West African states between 2011 and 2016. The corruption came to light following an investigation by the Serious Fraud Office.

As it happens, the legal authorities in the USA have also fined Glencore on related charges. With Glencore again pleading guilty, the company were obliged to pay US authorities over $1bn. A smaller fine was levied by another court in Brazil and there are ongoing corruption investigations, with possible charges, in the legal systems of the Netherlands and Switzerland.

$800,000 in cash on a private jet

The Serious Frauds Office found that the company had paid $28mn in bribes to employees and agents “to secure preferential access to oil, including increased cargoes, valuable grades and preferable dates of delivery.” These actions were approved by the Glencore ‘African desk’ in London for oil operations in Nigeria, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea and South Sudan.

In one case, according to the SFO, two employees accompanied $800,000 in cash by private jet to South Sudan, only one month after it became independent. An intermediary paid by the company also flew cash on a private jet to bribe officials in Cameroon.

All of these are extremely impoverished African countries and the Glencore criminality lifts the veil ever so slightly on the extent to which Western companies work hand in glove with local corrupt elites to fleece the mass of population out of the real value of their natural resources and wealth. Press reports give no indication of who was in receipt of the Glencore bribes but we can be sure that much of it will have found its way to banks and properties in London, the world’s capital for dirty money.

What is noted in all of this reportage, however, is the complete absence of any charges against individual employees or the directors of Glencore. Who signed off the withdrawal of hundreds of thousands of dollars? Who signed off the payment of tens of millions of pounds? Which directors knew about what was going on at the Africa desk?

The judge in the London trial made the point that “the facts demonstrate not only sustained criminality but sophisticated devices to disguise it”. But while the company can plead guilty and thereby buy itself an amnesty, there is as yet no effort being made to charge individuals in the company. There are no bosses in the dock. It seems that the higher up you go, the bigger your get-out-of-jail-free card.

Fined for money-laundering for Mexican drug cartels

This is part of a pattern. Last December, the HSBC bank was fined £64mn for its failure to put in place adequate safeguards against money-laundering. A BBC report noted that the Financial Conduct Authority cited examples of “poor controls, including failing to spot suspicious activity” on the account of a person linked to a criminal gang. Some HSBC customers might have ended up getting nicked, but no bank directors were.

This HSBC case was not linked to another, when a huge fine imposed on the bank by US authorities in 2012, again for money-laundering. The US Department of Justice fined them $1.9bn for failing to stop money laundering by Mexican drug cartels. Again, no directors were jailed.

HSBC is not alone. NatWest bank was also fined in the UK – this time for £265mn – again for failing to prevent the laundering of as much as £400mn of dirty money. One person suspected of money laundering carried nearly three-quarters of a million pound into a branch of the bank in black bins bags. NatWest “deeply regretted” its failure to ring alarm bells, but again…no directors or bank employees were held culpable.

The only instance of a banker being put in jail was Nick Leeson, the so-called ‘rogue trader’ who lost his company, Barings Bank, $1.3bn in 1995. Leeson got six and a half years in jail but was scape-goated largely because he was a relative minion (albeit well-paid) and he also broke the company he worked for. His ‘exploits’ were later made into a film. In contrast, in 2009, a man who manipulated the futures market to artificially raise the global price of Brent Crude by $1.50 a barrel, was given a slap on the wrist, a £72,000 fine – peanuts to these guys – and banned from working as a trader.

Workers often killed at work…but no manslaughter charges

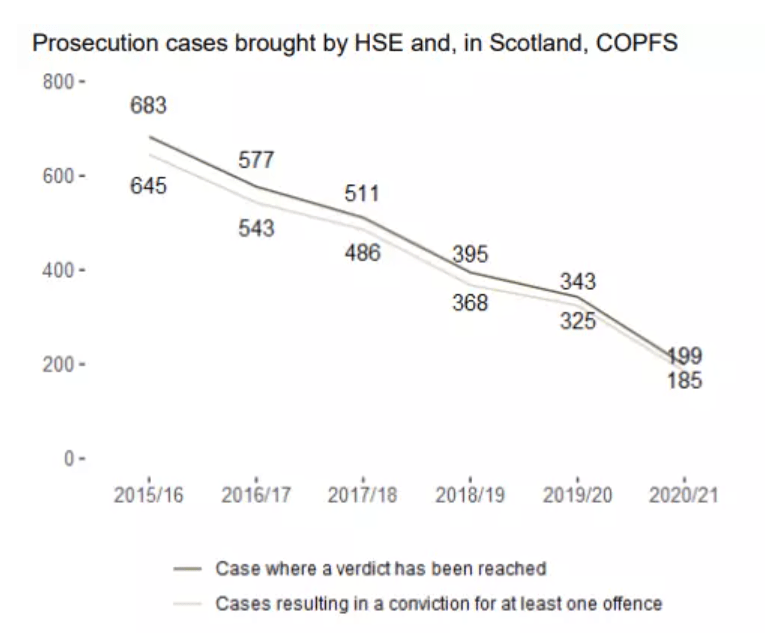

According to the Health and Safety Executive, 123 workers were killed at work in 2021/22 and 441,000 workers sustained an injury at work. We read occasionally of companies being fined after a worker has been killed at work, but how often do we hear of cases of company directors being jailed for manslaughter? As scores of workers are killed and tens of thousands injured every year, the number of prosecutions brought by the HSE is actually on the decline.

Next time there are riots in one of the most deprived inner-city areas of the UK, take note of how quickly the mainstream newspapers will demand ‘swift justice’ against anyone caught looting. If the past is anything to go by, ‘justice’ will be imposed quickly and mercilessly on any youth who get caught. Then take note of how many bankers, company directors and other bosses are jailed when their companies engage in criminal activity or when their negligence results in a worker’s death. Is answer is usually – in fact, almost always – none.

In the Glencore bribery case, the judge noted that in the company, within its London Africa desk, “fraudulent activity was endemic”. During the proceedings, the Serious Fraud Office asked for anonymity for the Glencore employees because it was considering whether or not to bring charges against individuals. Withholding names, we might add, also prevents authorities in the African countries concerned from pursuing those in receipt of the bribes.

Meanwhile, Glencore are laughing all the way to the bank. They are one of the world’s biggest and most powerful mining and commodity trading houses and they had record earnings of $18.9bn in the first half of this year. Losing a billion in fines is just one of their ‘overheads’, much like bribery that isn’t found out.

Helen Taylor, senior legal researcher at Spotlight on Corruption, a campaign group, welcomed the fine on Glencore, but added that “the big test for the UK justice system will be whether senior executives at Glencore who masterminded this egregious scheme will be successfully held to account and prosecuted”. (Guardian, November 3). We aren’t holding our breaths.