Andy Ford (Warrington South CLP member) continues his occasional series of articles on Soviet military history. [Title image reads – We stand in the Caucasus!]

November 1942 was the date at which the Nazi conquests in Russia reached their greatest extent, reaching deep into the Caucasus, as well as occupied territories stretching from Leningrad to the fringe of Moscow and on to Stalingrad. But the Nazi triumph was to be short lived.

After defeat at Moscow in December 1941 Hitler decreed a new strategy, code named ‘Case Blue’, for the Wehrmacht. They were to strike deep into the Caucasus to seize the oil resources of the Soviet Union located at Maikop, Grozny and maybe, at Baku on the Caspian Sea.

One of Lenin’s favourite sayings was “War is the continuation of politics by other means” and the invasion of the Caucasus shows this perfectly. Between the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1939 and the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Stalin delivered substantial quantities of oil to Germany. This was the fuel for the Nazi war machine, from the U-boats in the Atlantic to Rommel’s Afrika Corps. But, from the day of the invasion that supply was ended; and the failure to take Moscow and establish a vassal state meant that the Nazi oil stocks were low and getting lower. In June 1942 Hitler is recorded as saying that “Without the oil of Maikop and Grozny I must end this war”.

The Battle of Stalingrad [see article here] was itself secondary to Case Blue. It was necessary to secure the eastern flank of the German advance, preventing the Russians from cutting off the German troops in the Kuban, Chechnya, Ossetia and Azerbaijan, where the oil fields were located. So, Hitler broke a key rule of warfare – he divided his forces. Army Group South was separated into two groups, A and B. Army Group A was to take the oil fields and Army Group B was to advance to the River Volga and Stalingrad, then hold off the Red Army.

Army Group A consisted of three Panzer divisions, a total of about 500 tanks. Also, each had 900 motorised troops in half-tracks and 1200 motorcycle troops, in addition to their armour. There was also the Slovak Mobile Infantry Division, two well equipped divisions of mountain troops and, after a delay, 2 divisions of Romanian mountain troops. It was still a remarkably small force to conquer an area larger than Germany itself.

Opposing them, the Soviet troops were a mixture of battered remnants of the defeats in Crimea and Ukraine, training formations and low-quality border guards. They had hardly any tanks and once the Germans cut the rail line from Stalingrad, they could not be resupplied. Instead, they had to rely on American and British tanks supplied by lend-lease through Persia (Iran) – which were far inferior. The situation only improved in August when the high command sent 4 brigades of elite airborne troops to the theatre. Soviet sailors redeployed from the Black Sea fleet and Azov flotilla also proved their worth in key battles on the Black Sea coast. In addition, there were many NKVD troops in the region who had been suppressing nationalist movements in the restive Caucasian republics.

The Russians were also handicapped in that a lot of the senior generals were appointed for their ties to Stalin rather than any military ability. Overall commander, Marshall Semyon Budyonny, and Generals Tyulenev, Cherevichenko and Grechko, had all served in the ‘Red Cavalry’ of the Civil War and had been involved in Stalin’s sabotage at the Battle of Warsaw in 1920 which resulted in the strategic defeat of the Red Army and a drastic loss of territory to the USSR. Budyonny had been moved to the supposed backwater of the North Caucasus after presiding over the debacle in the Ukraine in 1941, which included the biggest encirclement and surrender in history, where 500,000 Soviet troops were captured. Now the Caucasus was a backwater no longer.

Early success

Initially, the German attack in July, led by Field Marshall Wilhelm List, went further and faster than anyone had expected. They achieved complete surprise and advanced to, and crossed, the River Don on pontoon bridges. The Soviet commander, General Tyulenev, was relieved of his command on 22nd July, but incredibly Stalin appointed no successor for 4 days. In the ensuing chaos the Germans entered Rostov-on-Don, the ‘Gateway to the Caucasus’ on 23rd July, racing to secure the critical road and rail bridges across the 150m wide river.

They found the bridges in chaos with panicked Russian troops fleeing in a huge traffic jam. No effort had been made to mine or crater the bridges and in fact the only damage was caused by the Germans themselves when they were shooting up the Soviet convoys and exploded an ammunition truck, destroying one span of the crucial railway bridge.

Despite Stalin’s “legendary” Order 227 ‘Not A Step Back’, the next few weeks were filled with defeat and disaster for the Soviet Union. Once the bridges over the Don were captured the Germans advanced at up to 80 km a day, while the Russians neither defended nor retreated. Eventually Budyonny, way out of his depth, ordered two fresh tank brigades into a disastrous counterattack which ended with their encirclement and 15,000 Red Army soldiers captured.

To Hitler it felt like the early days of Operation Barbarossa all over again, and drunk with arrogance, he ordered a whole German division to Rzhev, in central Russia, reinforcements to Stalingrad and the Nazi troops in the Crimea to Leningrad.

German successes continued: on 31st July the key railway junction of Salsk fell, virtually undefended, so allowing them pretty much a choice of routes of attack into the Caucasus. What was almost a pursuit, then began. The Germans divided into 5 prongs, which quickly became very spread out.

The Kuban

One prong of the Wehrmacht headed into the Cossack heartland of the Kuban from mid- August. Budyonny ordered a stand to be made at Krasnodar, the region’s capital, but half of his troops did not even have rifles, and civilians tasked with digging anti-tank ditches had to find their own shovels. Realising they were about to be assaulted by 3 full divisions of the German army they wisely beat a retreat, and the city fell.

The Soviets made a much better defence of Novorossiysk on the Black Sea coast, using redeployed sailors from the Black Sea Fleet as their main forces. Just as at Stalingrad the Luftwaffe bombed the city flat but the resulting ruins and rubble made it a death trap for the German infantry. After weeks of brutal street fighting in the shattered factories and apartments, by 9th September the Nazis did control the centre of the city but could not get past the bombed-out factories on the edge of town and they made no more progress down the Black Sea coast.

The seizure of Maikop

A second prong was directed to the oil fields at Maikop. These were the closest oil resources to Rostov and an elite unit of German commandoes attempted to seize the oil fields using disguise and deception. Masquerading as Russian NKVD troops they drove right through the Russian lines, joining the headlong retreat. Once at Maikop they first destroyed all communications in the city before issuing false orders to evacuate. They were partially successful, and the town fell on the 8th August – but the oil storage tanks were ablaze. Worse, most of the ‘Maikop oil fields’ were in fact another 45 km away and when they got to them, they found them sabotaged so effectively that whole new wells would have to be drilled if any oil at all was to flow.

Into the mountains

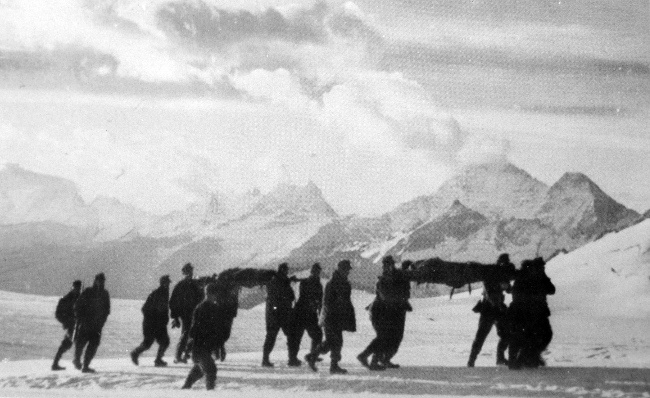

Goebbels thought it would a great propaganda coup to seize Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe, and the German mountain troops, with armoured support, were sent into the High Caucasus. Through forced marches and bold attacks, they did indeed seize several of the mountain passes, which lay undefended, and hoisted the Nazi flag over Mount Elbrus. But the narrow mountain roads were terrible for logistics – but perfect for ambushes – and rendered the German Panzers ineffective. It took four days to take food and ammunition on mule trains up to the mountain troops, and four days to evacuate a casualty. It was a pointless victory and Hitler was furious when he found out.

The Kalmyk steppe

Another prong of Army Group A fanned out into the Kalmyk steppe, an arid region bordering the Caspian Sea. The region had hardly any water and few settlements to support the infantry. All the Germans could do was to fortify isolated strongpoints in the steppe, sending out long range patrols to try and reach the Caspian coast and to disrupt Soviet transport of oil on the coastal railway, which they did achieve on a few occasions. Later it emerged that 150,000 tonnes of oil from Baku had moved north to supply the Russian war effort while the Germans were camped out barely 50 miles away.

The oil of Grozny – the main prize

To reach the Grozny oil field the Germans had to drive far to the south, to Chechnya, 500 miles from Rostov and the River Don. Budyonny made no stand at the key city of Stavropol on the road to Grozny, which fell in 75 minutes on 5th August, and just 6 tanks captured the next town of Nevinnomyssk.

On 26 August the Germans reached the River Terek at several points, and it was clear that a crossing would face significant resistance. The Terek made a natural defensive line for the Russians, the German tanks were now permanently short of spare parts and fuel, and their supply lines faced constant attack from bypassed Soviet units. But still, they crossed the river on the night of 2nd September near Mozdok, North Ossetia, but were unable to expand their bridgehead. They came under sustained air attack and a night bomber flown by a female pilot, Marina Chechneva, took out the pontoon bridge.

It was at this point that Hitler realised that Case Blue was not going to plan and relieved Field Marshall List of his command. He accused him of not following orders. This was at least partly true – he had sent his tanks up narrow mountains roads, allowed a futile diversion to plant a flag, and sent his infantry into the wilderness of the Kalmyk steppe – but that only reflected the chaotic decision-making in Berlin, the multiple objectives set, and the insufficient resources allocated. Amazingly, Hitler now decreed he would run things – from Berlin, over 2000 miles away!

The Nazis made one more desperate attempt to secure the objective of the whole campaign – Grozny and its oil. The elite SS Viking Division was transferred, and on 26th October, a panzer assault was launched towards Ordzhonikidze (now Vladikavkaz), which if successful might open the road to Grozny and the oil fields. They were successful at first, taking 7,000 prisoners in the town of Nalchik, but when they turned east towards Ordzhonikidze, they ended up entangled in minefields and surrounded on three sides. On 6th November, a Soviet counterattack surrounded the 13th Panzer Division and although they fought their way out it was at the cost of leaving behind most of their equipment – including 80 tanks and 1,000 trucks. It was a disaster, and the Nazi strategy was at a dead end. They could do no more.

A balance-sheet

The Germans had captured a huge amount of territory but had not secured a single one of their strategic objectives. They had not secured the oil fields – Maikop was unusable and Grozny unreachable – they had not encircled the main elements of the Red Army who stood ready to counterattack, and they had not cut the railway from Baku to Astrakhan.

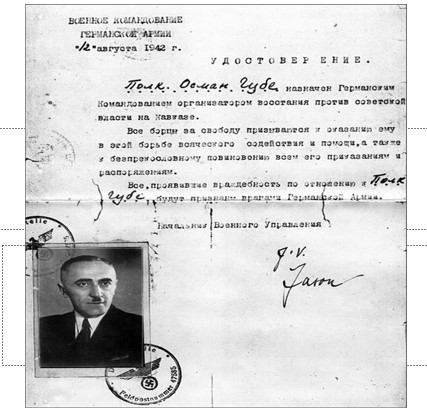

The hoped-for uprisings of the Muslim peoples of the Caucasus did not materialise despite the best German efforts. The occupiers went easy on the food requisitions and even parachuted a force of around 1,000 special forces (700 Chechens and 300 Germans) into Chechnya, hoping to link up with a low-level insurgency in the Chechen mountains. Hitler even appointed a Chechen stooge, Osman Gube, as future leader of a Chechen puppet state. But his group could not win over the native Chechen insurgents since it was quite clear that the intention was not Chechen independence but control over the oil of Grozny. Osman Gube was captured by local Chechen police in January 1943 and hanged shortly after.

But on the other hand, there was no partisan movement to speak of in the occupied areas as the Caucasian peoples had suffered so much under Stalin’s forced collectivisation and NKVD repression, including the massacre of 14,000 Chechen and Ingush dissidents in 1937. The Stalinist regime had no mass base of support; but neither did people want to be the subjects of a Nazi empire.

With the Jewish population the Nazis behaved in the Caucasus just as they did elsewhere in the Soviet Union. The Einsatzgruppen murdered 50,000 Jews in specially adapted gassing vans. They tracked down and shot any so-called ‘Commissars’, i.e., anyone involved in the local administration or Party. They also murdered hundreds of mentally-ill patients in Stavropol and 214 disabled children in Yeisk near Krasnodar.

Nazi failure

The Nazi forces on the River Terek and the Kalmyk steppe now faced increasing counter attacks while they were 500 miles from their main supply base. All materials had to come across one rail and one road bridge at Rostov-on-Don, and the frontline became more and more difficult to maintain. Then, on 19th November, the Red Army attacked at Stalingrad and four days later the German command in the Caucasus learned that Army Group B was surrounded.

Still Hitler refused permission to pull back from Chechnya. The German troops in the steppe outposts now faced encirclement and a strong Soviet push from Stalingrad towards Krasnodar was launched towards Christmas, which threatened to cut off the entirety of Army Group A. It would have been a second Stalingrad. But due to poor Soviet communications and tenacious German defence it did not happen. Instead, the German forces retreated across the Don more or less intact on 6th February 1943.

Nazi forces had suffered around 125,000 casualties, and the Red Army 247,000 dead, missing or captured. But the Caucasus was liberated, and Nazi Germany had no Russian oil. Case Blue had failed.