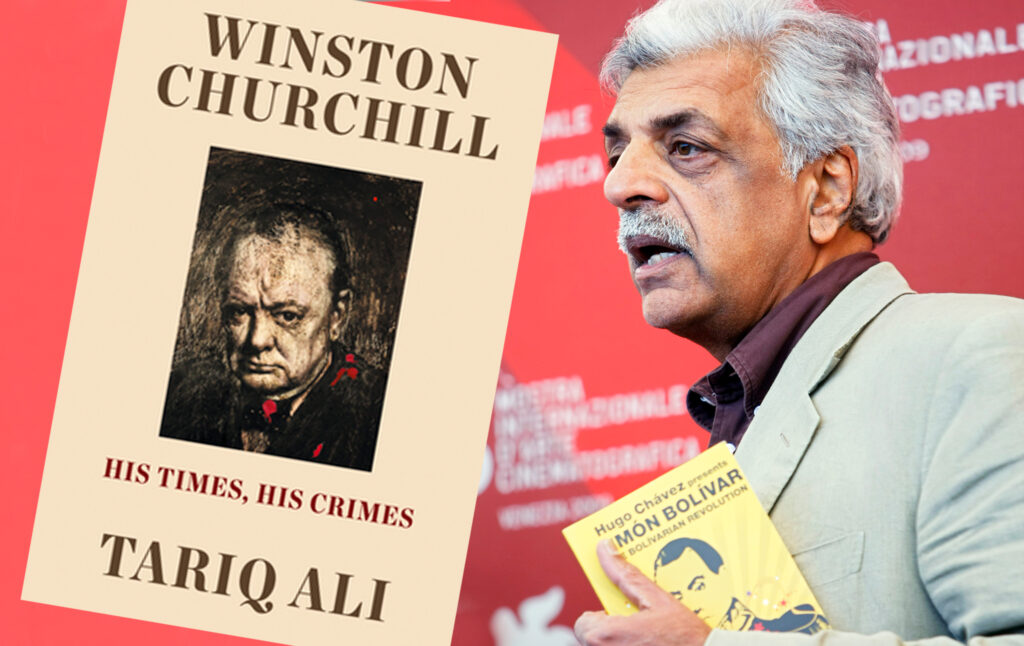

Mark Langabeer (Hastings and Rye Labour member) looks at a myth-busting book by Tariq Ali (2022 – Verso)

This book, given to me as a Christmas gift, is a good antidote to the favourable press given to Winston Churchill. The author states that the aim of his book is to refute the claim that Churchill was a standard bearer for freedom and democracy. A while back, the BBC 2 Newsnight programme conducted a poll, asking who was Britain’s greatest person in history. The majority voted for Churchill. That was hardly surprising, given the coverage by most media outlets.

Ali traces Churchill’s upbringing – a descendant of the aristocracy, with all the privileges that entailed. Like many of the families of the ruling class in Victorian times, the relationship between parents and their children was a distant one. In a letter to him, his father (an MP) regarded Winston as little more than a failure. The young Winston was determined to prove him wrong. He enlisted into the Army and served in the Boer War. He was captured and managed to escape, which became newsworthy at the time. Many senior officers, including Kitchener, regarded Churchill as a glory hunter. Later, he became a war correspondent, a job at which he did excel, and then a Member of Parliament for the Liberal Party.

Ali confirms that Churchill did actually support social reforms in the period leading up to WWI. The rise of Labour and the need for national efficiency were the primary reasons for this. A third of army applicants were regarded as unfit for active service. However, he was opposed to other reforms such as the extension of the franchise to women.

He was primarily a supporter of the British Empire. One of the fallacies about Churchill is that regarding his ability as a war leader. He was removed as head of the Admiralty during WW1 because of his decisions concerning the Gallipoli campaign. Later, he was given the post of Munitions Minister.

Workers’ hatred

After WW1, Churchill changed colours and joined the Conservatives. Hatred ran deep among wide sections of the working class towards Churchill. This was especially strong among miners because he agreed to deploy troops against them in South Wales. He was a “hawk” during the general strike and set up a paper called the British Gazette, which called upon people to volunteer to break the strikes.

His support for Empire was matched by his hatred for Bolshevism. He supported Mussolini, Hitler and Franco in crushing the labour movements in Italy, Germany and Spain. Churchill only opposed Hitler and other Axis powers when they threatened the British Empire. It’s not widely known but Churchill was also an antisemite. He declared that the Russian revolution was brought about primarily by “atheistic Jews”. This comment isn’t far removed from Hitler’s “Jewish-communist” conspiracy theory.

There is a widely accepted narrative that he was a visionary during the run up to WW2, yet he actually supported Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement of Germany until as late as 1938. His only quarrel was over rearmament. It was WW2, of course, that gave him the prestige that he hankered after. However, he was soon turfed out of office in 1945. The troops wanted social change and wouldn’t tolerate a return to pre-war conditions.

The author explains in detail the callousness of Churchill and his class. It was reckoned that over 3 million Bengalis died as a result of diverting the supply of rice and equipment for the war effort. General Wavell witnessed some of the deaths caused by malnutrition and disease. He urged a change of policy but it was rejected. In Churchill’s eyes, these people were dispensable.

Racist

The British Empire was premised on the idea that the peoples of colour were inferior. He was a racist who supported the suppression of Africans, Indians and peoples from the far East. According to Ali, Churchill was in favour of using poisoned gas against ‘uncivilised’ tribes and hated people with “slit eyes and pigtails”. The vilification of the Japanese people in general made even the use of nuclear weapons against them acceptable. It was claimed that this ended the war. However, as Ali states, it was really a demonstration of US power and a warning to the USSR. WW2 ended Churchill’s pretentions that Britain was a global power. The dominant imperialist power today is the USA, although they fear that China may be a rival in the future.

In recent times, there have been calls for the removal of statues that honour those that had got rich from slavery or imperialist plunder of former colonial countries. In some cases, direction action was taken. Ali takes the view that this would be a mistake. An alternative viewpoint should be on display so that people can judge for themselves. I think he is broadly right. I would like to see modest statues of people that have been at the forefront of struggles to improve social conditions.

In my youth, I spent time supporting the Grunwick strikers (1976/77), largely Asian women who fought for Trade Union recognition. Mrs Desai became their voice. A small statue in her honour would be a fitting tribute to the role that she played in this dispute. Readers will no doubt have others in mind.

Tariq Ali’s book on the crimes of Churchill gives an alternative view on the history of Empire and the role played by one of the most famous names in British political history. It’s reasonably easy to read and can help in debunking some of the claims made about Churchill’s so-called “greatness”.