By Michael Roberts

As usual, there were hundreds of sessions and papers at this year’s ASSA 2023, the annual conference of the American Economics Association (AEA). In this post, I shall concentrate my report on the mainstream economics sessions and on what I considered to be key topics and the most illuminating.

Let’s start with the US economy. In the big arena of the Grand Ballroom of the Hilton in New Orleans, we were treated to presentations by leading mainstream economists under the title ‘Economic Shocks, Crises and Their Consequences’. The title tells it all. The premise of mainstream economics is that market economies (theoretically) move smoothly along until hit by ‘shocks’ that push it off course. The job of economists is to get market economies back on course with some suitable policy adjustments and perhaps look for ways to defend the market economy from future ‘shocks’. There is no acceptance that there could be inherent fault-lines within the market economy itself – all problems are exogenous.

A long term view of inflation

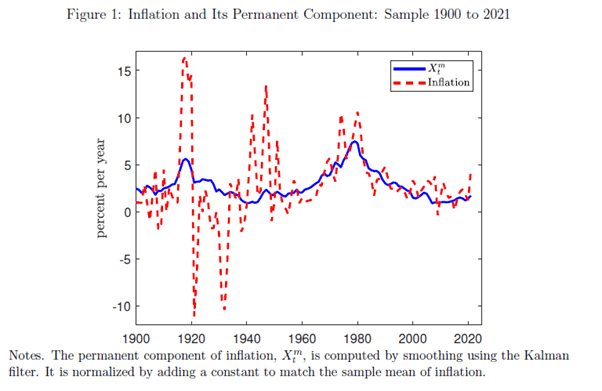

The panel kicked with Stephane Schmitt Grohe from Columbia University on the drivers of the current inflationary surge in the US. Taking a long-term view, Grohe noted that there has been only one long inflationary period in the US from about the late 1950s after the Korean war, the Vietnam war and leading up the 1970s inflation decade. After that, inflation moderated and reached lows before the COVID pandemic spike. Will the current spike become long term as in the 1958-80 period or not? Grohe argued not; and is more likely to be temporary if you isolate what she called the ‘permanent component’ of inflation over the very long term (Figure 1).

This permanent component is just a statistical artefact and Grohe offered no explanation of what drives it. Maybe she should read some Marxist explanations.

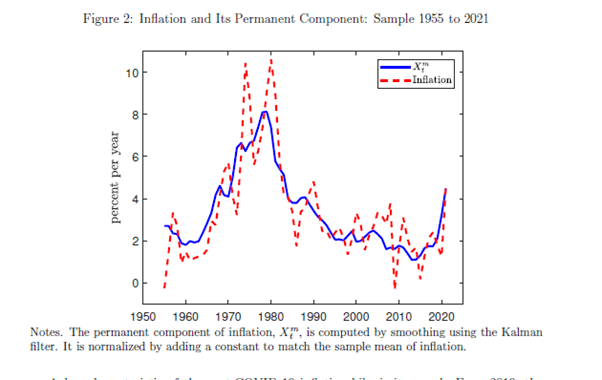

Nevertheless, I sympathise with the view that, if the major economies are entering another decade of low growth, post-COVID, then the current inflation spike may not be permanent. On the other hand, it does appear from the post-1950 data that inflation rates move in (60-year) cycles and economies could now be entering a new up-phase (Figure 2).

The factor of real interest rates

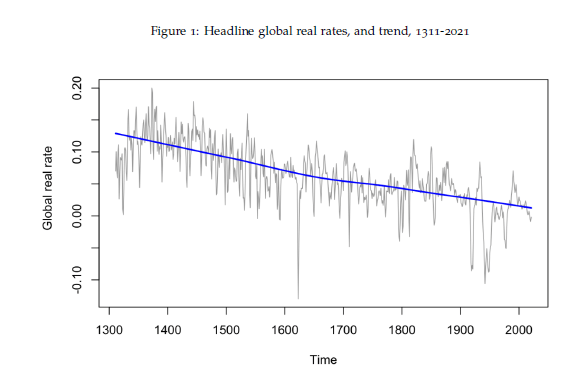

Kenneth Rogoff of ‘Growth in the Time of Debt’ fame, also opted for the view that inflation would stay low because there was a long-term trend of falling real interest rates.

However, if debt, both private and public, continued to rise, then real interest rates were likely to rise to the point where they squeezed growth – and we would have another period of ‘long depression’.

Can future shocks be ameliorated?

The contribution of Kristin Forbes, former Bank of England council member and from MIT, was revealing. Ironically, Forbes opened her presentation by reminding us of what Nobel prize winner and doyen of the neoclassical school, Robert Lucas, confidently claimed back in 2003, that “the central problem of depression-prevention has been solved”. Has Lucas been proven right? Obviously not, given the Great Recession of 2008-9 and the pandemic slump of 2020. But these were ‘unpredictable’ shocks to the system. So we need to find policies can help cure the economic damage and perhaps find ‘preventions’ against future shocks.

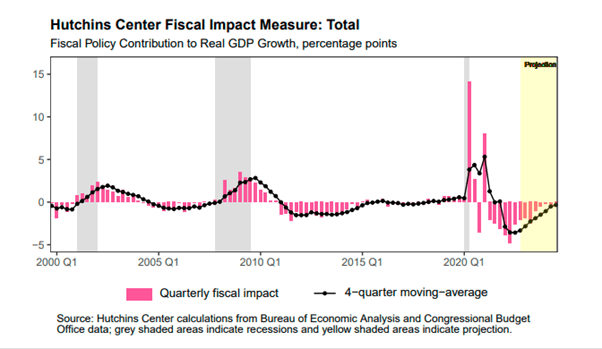

Forbes was optimistic that fiscal and monetary policy could ameliorate future shocks, as fiscal support during the COVID pandemic proved. Indeed, the conclusion that fiscal policy can work was promoted by nearly all the presenters in this session and others. For example, Jason Furman, former White House economic advisor, argued that US fiscal support during the pandemic had risen to nearly 25% of GDP in the US, mainly through unemployment insurance packages of up to 15% of pre-pandemic incomes and had saved Americans. That’s why unemployment was now so low and why US GDP recovered, if still short of pre-pandemic levels.

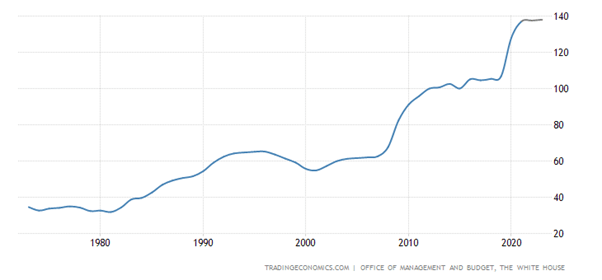

The problem now was that US debt, both public and private, was at record highs.

US public debt to GDP (%)

This, according to Forbes, was threatening to create ‘new fragilities’ and even a financial crisis. Indeed, Forbes reckoned ‘time was running out’ in avoiding new ‘shocks’ as revealed by the sharp rise in bond yields, and the lowest returns on bond investments since 1788! So what’s the answer? Forbes called for more prudential regulation of the banking system – good luck with that! As for whether there had been sufficient progress in macroeconomics to meet the claim that Lucas made 20 years ago, Forbes concluded that it “was too soon to claim victory”. Indeed. More like mission impossible.

Larry Summers and his thesis of ‘secular stagnation’

And then came Larry Summers, former White House advisor and Treasury secretary, and the epitome of modern orthodox Keynesianism. By Zoom to the session from what appeared to be a hotel balcony in the sunshine of a tropical island, Summers discussed the current economic situation and whether his thesis that the major economies are still in ‘secular stagnation’ that he propounded many years ago was still place, at the same time as I developed my Long Depression theory (with different causes).

former White House advisor and Treasury secretary,

speaking to the Conference remotely

On the immediate situation, Summers told us from his deckchair that ‘unemployment needed to rise to get inflation under control’. But he was unsure whether the stagnation thesis still held post-COVID. Apparently, this was ‘unknowable. But if pushed, he thought that, maybe, real returns on assets would rise due to innovative technology, a ‘green’ investment boom and rising consumption as households saved less and borrowed more. A new period of boom rather than stagnation was then possible, as after the end of WW2. But meanwhile people will have to swallow the bitter pill of falling living standards and rising unemployment.

If you think about it, a new boom is only possible if the productivity of labour rises at a much faster rate than seen in the last 20 years. And that would only happen if productive investment took a leap forward. In turn, that will only be likely if the returns (profitability) on that productive investment rises.

The impact of home working

In the mainstream sessions, there was much discussion on whether working from home – the phenomenon of the COVID lockdowns was here to stay and whether it would raise productivity growth. John Fernald and Huiyu L from the San Francisco Fed reckoned that working from home had risen from 5% of employees before the pandemic to 50% during the pandemic and now stabilising at 30%. This had led to a 6% improvement in productivity from (low) pre-pandemic levels. Another survey by various economists found that workers surveyed were sure that their productivity had risen by working from home.

And the great pessimist of long term productivity growth, Robert J Gordon, in a new paper, argued that, after growing at the dismal annual rate of 1.1 percent per year during the decade of 2010-19, private-sector U.S. output per hour surged ahead in 2020-21 at an annual rate of 3.1 percent, faster even than achieved in the “dot.com” decade of 1995-2005. Gordon claimed that most of these high-productivity-level industries were in the service sector and were characterized by work-at-home during the two pandemic years, and their high productivity growth in those years contrasted with the slow or negative productivity growth in “contact services” where workers had to be present on the job.

Prospects for higher productivity

That’s the story of home working, according to these studies. But what about the prospects for higher productivity growth longer term? One paper suggested that, as population growth slowed, as it is, it would stimulate higher productivity.

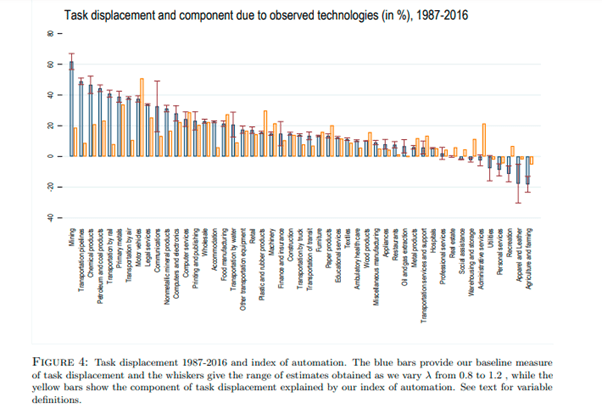

But the expert on the impact of technology on productivity is Daron Acemoglu (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). In giving the AEA’s distinguished lecture at ASSA, Acemoglu explained his theory based on detailed evidence that technology can be beneficial to productivity and employment, but ‘distorted technology’ can do the opposite. I have discussed his arguments before. Acemoglu’s own extensive research on inequality and automation shows that more than half of the increase in inequality in the U.S. since 1980 is at least related to automation, largely stemming from downward wage pressure on jobs that might just as easily be done by a robot.

Which labour sectors lose or gain from new technology?

For me, Acemoglu’s argument matches that of Marxist economic theory, namely that technology can boost productivity and improve living standards, but because it is only introduced under the profit motive, much technology is not for social needs, is wasted and is at the net expense of labour. I shall return to this issue when I review the ASSA papers from the radical wing of economics.

The impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Of course, the other big issue in the mainstream sessions was the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This was approached from several angles: the cost to lives and infrastructure; the cost of reconstruction after the war ends; the rise in energy and food prices globally; the possible permanent changes to the geopolitical configuration of the world. Underlying all the panel discussions and papers in the mainstream sessions was the clear premise that not only must Ukraine be supported in its fight to sustain its borders and sovereignty, but this was also a fight for ‘liberal democracy’ against autocratic tyranny from Putin’s Russia.

In the main panel session, speaker after speaker started from this premise and also from the view that post the war, Ukraine should become a model capitalist democracy. This was to be achieved by massive foreign investment in the economy; by maintaining a huge military defence budget of up to 20% of GDP; and by ensuring that all investment in infrastructure and public services was directed and controlled by a European reconstruction agency that would have a veto over any projects. The latter was to ensure that corruption was avoided (remember Ukraine was regarded as the most corrupt state in Europe before the war).

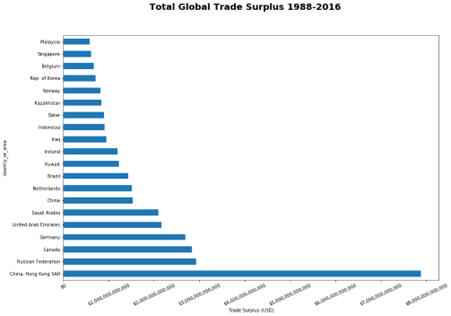

Effect of economic sanctions against Russia

Oleg Itskhoki (University of California-Los Angeles) discussed the effectiveness of the sanctions against Russia. He found that the financial sanctions had had little effect. The trade sanctions up to now had also not worked as Russia was running a record trade surplus by in selling oil and gas. So the ruble had remained very strong. But this might change, now that energy import bans and price caps are being imposed by the European Union on Russian energy exports. That remains to be seen in 2023. It may depend on whether Russia can sell its energy to India, China and Turkey and build new trade relationships with these and other countries. Sanctions on technology and the withdrawal of foreign companies and investment should eventually weaken Russia’s economic performance longer term.

The key question for me (which naturally was not discussed) was whether Ukraine would become a vassal state of US and Franco-German imperialism, with its investment and economic decisions controlled by foreign banks and companies and whether the people of Ukraine would find themselves subject to the most neo-liberal regime in Europe, with labour rights removed and complete deregulation of corporate activities; while also subbing huge amounts on military spending to defend the country from a wounded Russia – and what would happen to the minority Russian speaking enclaves in the east? No answer there, of course.

‘Economists should give up on the big ideas’

As I said above, mainstream economics starts from the premise that capitalist economies can grow evenly and steadily based on market competition; and so inequalities and crises are outside shocks to that equilibrium. As Nobel prize winner Esther Duflo put it in her AEA lecture in 2017 economists should give up on the big ideas and instead just solve problems like plumbers “lay the pipes and fix the leaks”. This follows Keynes’ famous remark that economists should be like dentists – sorting out troublesome teething problems so that capitalism can then run smoothly. Plumbers, dentists, engineers, doctors – but not, it seems, social scientists, let alone scientific socialists.

The question of whether mainstream neoclassical economics bears any relation to reality was taken up by of all people, Gita Gopinath, deputy managing director of the IMF and the rock star of mainstream economics. At the special AEA lunch to commemorate 60 years since two Chicago economists Robert Mundell and Marcus Fleming developed an equilibrium model of international trade, Gopinath reviewed the model’s connection to the real situation in international trade.

Does the mainstream international trade model match reality?

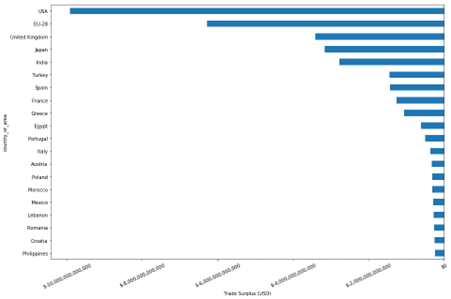

The Mundell-Fleming model of international trade reckons that if countries let their currencies ‘float’ that will ensure that the balance of trade with other countries will move to equilibrium as the changes in the prices of exports and imports on a trade-weighted basis will bring exports into line with imports ‘at the optimum’ for growth and employment. I have discussed the Mundell-Fleming model here before. But what did Gopinath conclude?

Gopinath told us that she taught this model to her students at Harvard University, but had to admit “in the real world” it does not work. Everywhere countries had chronic trade deficits or surpluses in the floating exchange rate world.

That’s because ‘prices are sticky’. Moreover, in a world where the US dollar is dominant in trade, the movement in the trade-weighted index is irrelevant; what matters is the rate to the USD. This means that devaluing the currency to boost exports won’t work because so much of trade is in dollar terms. All that happens is there is a fall in imports and thus domestic consumption – so Mundell-Fleming is not ‘optimal’. And dollar strength also deflates consumption globally.

What about capital controls to stop the outflow of financial assets? Gopinath reckoned it would have only limited success, as would other measures like hedging a currency against the dollar or FX intervention by central banks. Yet the Mundell-Fleming model remains the basis for IMF policy.

IMF terms for $3bn loan to Egypt

Indeed, this is precisely the policy just imposed on the Egyptian government in return for IMF funding. The government took a $3bn loan from the IMF in return for austerity measures and an agreement to ‘allow’ the currency to devalue (it’s now down 40%). As one paper put it: “We provide a theory of fear of floating, the ubiquitous policy among central banks of preventing large fluctuations in exchange rates. In contrast to the Mundell-Fleming paradigm, we show that an exchange rate depreciation does not play the role of a shock absorber—rather it can be contractionary and make more the economy vulnerable to a self-fulfilling financial crisis.”

So the Mundell-Fleming model is far from reality and alternative policy solutions in a world of dollar dominance are limited in protecting a country’s living standards and employment. But no matter, the Mundell-Fleming model of international trade remains at the core of mainstream economics teaching in the universities. Fiction rules over reality.

In the next post, I shall review the sessions by radical and heterodox economists at ASSA.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

The original blog includes links to websites that automatically download a PDF file. Those links have been omitted.